Powered by 16 strong backs, the 36-foot-long Montreal Canoe practically charged down the river towards the nation’s capital.

Weighing 275 pounds, it was a remarkable sight on Ontario’s Rideau Canal, but even more remarkable for the difficult questions being asked within. What does a reconciled Canada look like? How do we mend the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians?

Heavy questions. The kind of conversation conventional wisdom says isn’t fit to be had in the company of strangers. Yet, it’s this precise lack of public discussion 16 Canadians set out to tackle. Calling the 10-day journey Connected By Canoe, in-boat discussions about reconciliation with Canada’s First Nations were at the heart of this Canadian Canoe Museum-sponsored initiative. The team traveled 211 kilometers on the Rideau Waterway, from Kingston to the nation’s capital, Ottawa.

Their timing celebrated Canada’s sesquicentennial of Confederation, while coinciding their arrival with the opening day of the Community Foundations of Canada conference. The diverse group represented Canadians of many backgrounds, including several First Nations people and new immigrants. And in the way journeys of distance and heart open people up then bind them together, soon it seemed entirely normal to discuss thorny issues with new friends who were mere strangers days ago. No one doubts the integral role the canoe played in Canada’s past.

The Question The Connected By Canoe Journey-Makers Asked Is, Can The Canoe Now Guide The Country To A More Unified Future?

Ten days later, when they arrived in Ottawa, they had a lot to say. On the following pages, five participants from the voyage reflect on the journey and share their ideas on what a reconciled Canada really looks like, and how the canoe can help get us there.

James Raffan

Former executive director, Canadian Canoe Museum // Seeley’s Bay, Ontario

Connected By Canoe started with the idea the canoe can be as relevant to the future of Canada as it is undeniably relevant to its past. It was fun, but also a really effective way to bring people together to discuss things hard to talk about.

Many of the stories we hear of the intergenerational effects of conquest are just horrific. The information is out there, but to be sharing a meal or portage carry with someone with a personal story is very different than reading about it in a newspaper. One memorable revelation was from one of the First Nations paddlers on the journey. He said, “I thought you guys”—meaning white, European Canadians—“I thought you guys knew and didn’t care, and it turns out you don’t know, and now that you do, I see the angst on your face.” It’s a breakthrough.

The term reconciliation is a loaded and fraught bit of language in the sense reconciliation at its core is between Indigenous people and the federal government, which hasn’t honored treaties.

Connected By Canoe Is Absolutely No Substitute, It’s Simply One Idea—The Intensity Of A Canoe Journey Can Bring People Together

My hope is people will pick up the idea and use it.

Connected By Canoe was an intentional effort to show how the canoe can be relevant as a leadership force in a country needing to do some soul-searching. We can’t undo the wrongs of the past, but we can create a path forward.

When you put people in an isolated social setting with the common goal of getting from A to B, sharing food, sharing helplessness in the face of the weather, camaraderie grows. These social interactions occuring in the canoe fundamentally changed how people relate with each other.

What Does A Reconciled Canada Look Like?

Escaping our assumptions. The only way you can get an inkling of what those are is to take a risk; talk and listen to different people. And a canoe trip is a wonderful place to do this.

Erick Mugisha

Nursing student, Loyalist College // Peterborough, Ontario

I went on a five-day canoe trip the summer prior to Connected By Canoe. I had been living in Canada for only a couple months then. I just loved the clean water—it made me feel so good and I felt a responsibility to keep it healthy. Many people in Canada get in a canoe for fun, but you are really missing something if fun is all you feel.

After the first canoe trip, I wanted to share what I felt. I feel like the Earth is like our mother who raised us and provided us with everything. What’s the point of being disrespectful? It’s like we are troubled children—we’ve given her so much trouble, but she takes it as a challenge and keeps on giving us what we need.

As Individual People, Pollution Is Often Not Our Own Fault

Pollution is something someone else did. You don’t have to be like the people who misused the environment, but you do have to take responsibility for the way the environment is now and make it better.

Reconciliation for Canada and First Nations is maybe similar. We can’t blame one another if we want to progress, we have to accept what happened and find something to bring us together to go forward.

As One Of The Youngest People On The Connected By Canoe Trip, I Enjoyed Hearing From Experienced Paddlers And The First Nations

I was inspired by their way of thinking—cherishing so many living things in this world. Canadians should have this knowledge of the Native perspective—it opens minds. Protecting the health of the environment could be what brings people together.

Kristen Ungungai-Kownak

Student, Carleton University // Ottawa, Ontario

The question I brought to Connected By Canoe was how to better connect the northern parts of Canada with the southern parts.

My heritage is Inuk. I grew up in Rankin Inlet until I was nine, then we moved to Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut. Now living in Ottawa, I see a disconnect. Not everyone has the opportunity to travel to the North, or vice versa, so I try to share what it’s like up north.

To Me, Reconciliation Looks Like Granting Everyone Access To Education

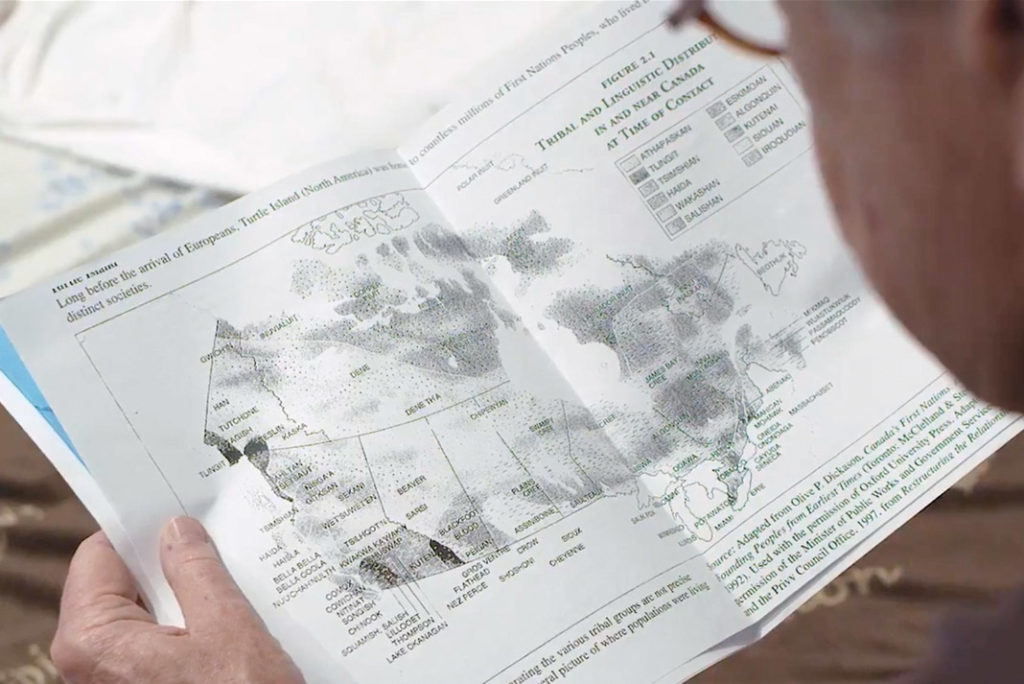

The real history of Canada isn’t taught everywhere and not offered to everyone. Only once it’s known, can there be a real conversation.

There’s a history behind why we need reconciliation, and why we need it now. My history program at university touches on Indigenous people, colonization and the effect settlers had on our culture, but had I not gone to this program I would not have had this perspective on my own history.

When I first learned, I’d felt betrayed. I thought about my family members and my friends’ families, how they were affected by residential schools. My parents never had this discussion with me, and my friends’ parents who went to residential schools were very closed off. For me, it was the first time learning why.

Through The Connected By Canoe Trip I Felt Uplifted And Inspired—It’s Not That Canadians Ignore The North Or Don’t Care, Many Just Need An Opportunity To Connect

On the trip, I presented throat singing to some communities. Traditionally its done by two women, but I split the group into two, with people on either side and taught them to throat sing together.

Sharing one aspect opens up conversation and curiosity, and people started asking questions about traditional gender roles and contemporary issues for First Nations today. It opened my mind to the communities in southern Canada—they are interested, and just need a chance to connect.

Gary Running

Retired // Seeley’s bay, Ontario

James Raffan knew I paddled the Rideau Canal every year during National Paddling Week in June. The Connected By Canoe group needed someone who knew the Rideau system well and could drive a van.

So, I became the roadie for the trip.

I Didn’t Know Much About Reconciliation, But James Was Stuck And Needed Help

As we went along, I realized what the whole thing was about; how the Canadian government treated its Indigenous people. It was a real eyeopener. I listened a lot. Growing up, I didn’t really know these things.

While they were paddling, I drove a bus and a big, long trailer. I had no experience at all—the whole thing was about 60 feet long. That was a rude awakening too. The Rideau Canal waterway is beautiful, with lots of fur trade history. I was happy to share my knowledge.

You know, we do a lot of talking, but we don’t always practise but we preach. I know so many people who know the commandments on the way in the church door, but forget them on the way out.

It Took This Trip To Show Me What Was Done To Canada’s Indigenous People

At one point we were going around a circle sharing stories, and when it came to my turn to speak I said I used to be a proud Canadian, but I’m not so proud anymore.

This history should be taught in the schools. I think maybe it’s a step towards reconciliation. I was never taught what went down. Schools and teachers don’t speak about it and they don’t teach about it and I would not have known if it wasn’t for this trip. I’m 64 years old. Many other people don’t know too.

Stephen Hunter

Algonquin Negotiation Representative // Bancroft, Ontario

There’s a real commonality once you get into a canoe. If you don’t work together in a 16-person canoe you’re not going anywhere. A lot was said on the Connected By Canoe journey about the canoe in general—cheemun to the Algonquin people. It’s iconic to us, indicative of everything we are. It was also a tool used to colonize the country. Imagine trying to use rowboats to navigate west.

The Canoe Was Integral To The New People In Terms Of Getting Into This Country, Mapping It And Colonizing It

It was great we did this journey, but it was a long time coming. There were lots of tears on the trip as people opened themselves up and talked about their personal stories.

The conversation needs to continue in order to heal some of the pain of the Indian Act and I think we’re on track. I have hope—not for me, but for my great-great-grandkids—this country is going to be a great place for them.

What Can Readers Do?

They can love the guy next door. Care about the person who lives down the street. Step out of the bubble you live in.

There’s no letsgetengaged.com or official engagement center. There are friendship centers and pow-wows and Indigenous tourism associations and many ways to engage with Indigenous communities. In terms of building a stronger community though, the answer lies inside the reflection in the mirror.

To have a full appreciation, you really need to reach out to the guy next door, listen to his story and share your own story. Doing this, like we did in the canoe, creates stronger streets, communities, cities and provinces. Caring about the guy next door is a lost art, and it’s one we need to revive. It’s so damn simple to me.

I See Reconciliation As A Continued Willingness To Engage With First Nations People

And an openness to adopting some of our values, and lending them to modern issues and problems.

For a long time, the system set out to break us apart and to separate us from each other. As we move forward, I believe you’ll see us come together as First Nations people, with our traditions and the profound respect we share for community. And by community I mean this great Earth—this Mother—we live on.

Community is in our animals and birds, our flora and fauna, and this connection we all share but many have forgotten. Reconciliation looks like a world of respect for each other, and all living things.

Text by Kaydi Pyette