One summer in Maine, as I hoisted my canoe for the quarter-mile portage around Allagash Falls, I noticed the stones at the landing were covered in streaks of dark green and red. Continuing over the rise, blinking sweat from my eyes, I stared vacantly at the trail scrolling beneath my boots. It was rugged and steep and full of rocks, every one of which was marked with red or green, or both, even at the height of land where I stopped to catch my breath. On the way down there were even more colorful streaks, which makes perfect sense because it’s easier to drag a rented canoe downhill than up.

From that day on, I’ve been a believer in Royalex, the green (sometimes red) miracle material that dominated the middle of the canoe market from its introduction in 1972 until 2014, shortly after plastics giant PolyOne acquired Royalex manufacturer Spartech and shuttered the Indiana factory where it was produced, citing insufficient demand from the canoe industry.

T-Formex: Esquif’s long-shot bet on a replacement for Royalex pays off

Jacques Chassé is also a believer. So much so that he gambled his company, Esquif, on creating a replacement for the famously durable material. While other canoe companies looked to fill the gap with high-end composites or rotomolded boats, Chassé never saw those materials as an option for the canoe company he founded in 1997 with an order of five sheets of Royalex. While Esquif had grown to employ about 20 workers at its Frampton, Quebec, factory, it never moved away from Royalex.

“The other manufacturers already had composite boats in their pocket or rotomolded boats in their pocket, so they were able to survive with that,” Chassé says of the years after PolyOne ceased deliveries. “We did not have that. For us, developing T-Formex was a question of survival.”

Royalex consists of a foam core sandwiched between layers of ABS plastic, with a very thin outer skin that provides UV protection and a slick surface that tends to glance off rocks and slide over shallow river bottoms. Those qualities made Royalex a favorite of canoeists for more than 40 years, particularly expedition paddlers and rental liveries who valued its nearly indestructible nature and middle-of-the-road price point.

Manufacturing Royalex, or any viable replacement for it, requires sophisticated chemistry and machinery to produce each layer of material, and still more complex equipment to bond them together in a process called vulcanization. Chassé was somewhat familiar with the final step, because he had proposed to Spartech that Esquif could take over the vulcanization to expedite delivery during the busy spring season. He knew nothing about Royalex’s real secret sauce—the formulation and manufacture of the three component layers. He decided to go all-in anyway.

“There are things that you will do when you are a believer, no matter the challenge,” he says now.“When I received the letter from PolyOne saying they will cease their operation, instead of panicking or feeling destroyed by that news, I saw it as an opportunity.”

Chassé bought up every sheet of Royalex he could put his hands on, expecting it to bridge the gap until he could introduce the replacement laminate he would call T-Formex. He spent 2014 working to reproduce the Royalex recipe. Chassé read everything he could find about plastics and began working with Polytechnique Montréal, a research university with a pilot plant where Chassé pursued his own version of the Holy Grail: A trio of materials that, when bonded together, will hold its shape after impact, slide over rocks and resist the sun’s ultraviolet rays—a material that won’t weigh too much and can be made in sheets with reinforcements where needed, such as the places that will become the bow and stern when the material is draped over a mold and thermoformed into the timeless shape of a canoe.

Chassé ran out of Royalex, and cash, in early 2015.

“I didn’t pay myself for six months, but I kept my longtime workers until I had to tell them one morning, I can’t pay you anymore,” Chassé recalls. He eventually let all his employees go, and Esquif went bankrupt.

Still, he believed. He gathered a few friends and investors and bought Esquif out of bankruptcy. He was convinced he could bring T-Formex to market, and that when he did the company would thrive like never before.

A void, and an opportunity

In the early post-Royalex years, Chassé remembers talking to paddlers at shows like Canoecopia or on his favorite local runs. “Quebec rivers are tough and rocky, and it’s part of our DNA to paddle them,” Chassé says. “We are involved in whitewater as well, and paddlers were telling us they really needed a material that is durable enough for that.” Those conversations gave Chassé the confidence that there was a strong market—more than that, a real need—for T-Formex, if only he could deliver it.

After more trial and error he developed what he calls an evolution of the Royalex formulation, and found a processor in the United States that could produce the core and the skin. Then he bought the shell of an autoclave in Texas, shipped it to Quebec, and spent months making it operational and converting it from steam to electric heating. This solved one of the problems that had plagued Royalex, Chassé says.

“Moisture doesn’t fit very well with plastic, so our equipment allows us to control the process much better. ”

By the 2016 model year, Esquif was shipping a full line of canoes in T-Formex and was soon thriving like never before. In the Royalex years, Chassé says, Esquif had always been in survival mode. That changed with T-Formex. “It became the second profit center we needed to support our growth,” he says.

Esquif has made T-Formex available to other canoe manufacturers and Chassé has explored its use in different industries. Finally, he says, because a canoe manufacturer owns the formula, the paddlesports industry is no longer vulnerable to the whims of a multinational corporation.

The path hasn’t always been a smooth one. When a factory fire halted production during the peak of the pandemic boom in 2021, Chassé gathered his employees and told them they would be making canoes again in a matter of weeks—and they did.

“If you want your team to follow you, you need to be inspiring. You’ve got to feel the confidence that you’re going to make it,” he says. “You’ve got to believe.”

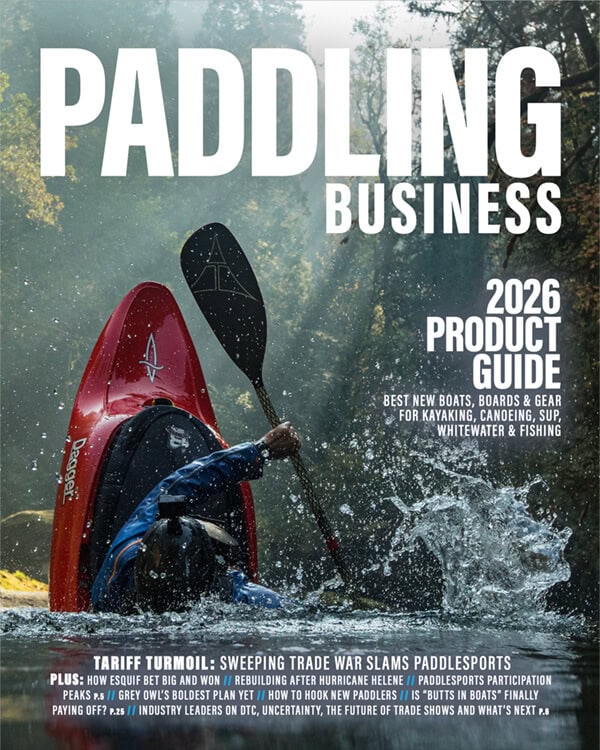

Jacques Chassé at Esquif’s factory in Frampton, Quebec. | Feature photo: Francis Vachon

This article was first published in the 2025 issue of Paddling Business.

This article was first published in the 2025 issue of Paddling Business.