If you’ve never wished you could capture the pulse- quickening feeling of a rapid or the expression on a friend’s face just above a drop to share and enjoy later, then might we suggest skipping this article. But if, like most paddlers, you recognize the power of an evocative photograph, there are no better teachers than the talent we’ve tapped for the very first Rapid Photo Issue.

COMPOSITION IS KEY

Spend time achieving a deliberte composition. To do this, I frame the scene and let the paddler move through. With experience you’ll know where the paddler is trying to go and anticipate the crux moment.

The only time you may want to follow a paddler through a rapid is in big water or for a generic, up-close paddling shot.

FOR STRIKING IMAGES, REMEMBER THESE RULES:

- The best shot is never from your boat and rarely from river level. Getting a good angle requires hiking.

- Put the paddler at the edge of the frame, not the center.

- Leave space for the paddler to move into—this builds suspense. Shoot for the moment of anticipation and create drama with the unknown.

- Don’t tilt the lens to make a drop look steeper than it is—this is always obvious and looks tacky.

- Shoot more than just the rapid—river canyons are beautiful!

If you have the time, shoot a lot. Try a different angle or zoom setting for every person that runs the rapid. You’ll learn a lot about what works, and what doesn’t.

METHODS OF ADJUSTMENT

STOP: A stop is a measured amount of light that is consistent across all methods of adjust- ment. For example, you can correct an underexposed image in one or a combination of three ways: slow down your shutter speed, open your aperture, or speed up your ISO by the required number of stops. On a bright sunny day, I’ll generally start off with a shutter speed of 1/800, ap- erture F/8, ISO 100. Then I’ll check the histogram and adjust as necessary, starting with aperture.

APERTURE: Along with shutter speed, aper- ture—or F-stop—controls the amount of light reaching the sensor. The numbering seems backwards—the smaller the number, the larger the aperture. Larger apertures permit low light shooting without sacrificing action-freezing shutter speed, but reduce the depth of field—the amount of fore-, mid- and background that is in focus.

SHUTTER SPEED: Faster shutter speeds stop action but don’t let in much light so they are challenging to use in deep, dark river canyons. Slower shutter speeds expose the sensor to more light, but moving objects like water, kayakers and paddles will blur. I consider 1/500 the absolute minimum when trying to freeze action. A better range is 1/800 to 1/1250. Shutter speed is the weakest of the three methods for adjust- ing exposure, because you only gain one stop of light going from 1/1000 to 1/500.

ISO: The digital equivalent to film speed. Lower ISO speeds absorb less light than higher ISO but retain better detail and color and less noise (digi- speak for grainy looking photos). As a rule, keep your ISO as low as possible for the situation.

SHOOT FOR THE LIGHT

Understanding light consists of a few basic rules mixed with experience. The most common mistake is to choose your angle for the rapid, not the light.

Early on, I thought sunny days were best for shooting action, since they allow medium apertures, fast shutters and low ISO speeds. Unfortunately they also limit your ability to shoot the angle you want.

Sometimes it can take years to get a shot because you have to camp at a certain location to shoot in the morning, on a run that flows only once a year. As you repeat rivers, remember key locations to shoot from, and what time of day will give you good light from that angle.

The most basic rule for whitewater lighting is to shoot with the sun behind you. It’s as simple as checking your shadow. This reduces glare, improves color saturation and, if the sun is low enough, lights up the paddler’s face. On the West Coast, this means shooting downstream in the morning and upstream in the afternoon. Vice versa on the right coast. At mid-day you are more or less limited to an overhead shot. If you have no option to get the sun behind you, use a good polarizer.

Although it is tricky since we can’t paddle in the dark, try to shoot near dusk and dawn for the most dramatic soft lighting.

If you’re shooting in the shade, try to exclude any direct sunlight from the frame, unless you see a specific bright spot that will highlight your subject. Don’t be afraid of mixed lighting when it can work to your advantage.

My favorite condition is when high cloud cover causes the light to naturally “lightbox.” Lightboxes are used for studio shoots and disperse the light so it’s even from all angles. You will need fast lenses or a camera with good high-ISO performance to maximize the light on these days, but you can shoot from your angle of choice with nice, even lighting.

GETTING THE RIGHT EXPOSURE

Any bright day on the river has a large dynamic range. This means that there is a vast difference from light to dark. Our eyes are amazing at taking in large dynamic ranges, while cameras are quite limited. Left to their own de- vices, cameras overexpose whitewater making it pure white and losing texture.

Welcome to the world of the histogram.

I shoot with my camera set to manual mode and adjust the exposure myself, using the histogram to achieve the right exposure. The histogram is a graph of the light captured by the camera sensor. It is the perfect tool for getting the correct exposure.

The most natural look for a scene where the dynamic range is too great is to adjust the exposure so detail is lost in the shadows (the left side of the histogram) but not the highlights—otherwise the image will appear washed out.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, the correct exposure for whitewater should look like the images at left. The graph needs to drop down before the right edge of the histogram to preserve highlight (whitewater) detail.

FINDING FOCUS

Another make or break component to any action shot is sharp focus. Digital cameras focus best on areas with straight lines and high contrast, not exactly the prime features of whitewater.

Switch your auto-focus from the shutter release to the AF-ON or AE-L/ AF-L button. Also put your camera in continuous AF mode for greater accuracy. You can find out how to do this in the manual of any DSLR.

I use the central AF point on my camera and focus using AF-ON to the anticipated crux and paddler visibility. Then I reframe my shot to the original composition and wait for the paddler to move through.

If the camera struggles to lock focus where you want, look for an outstanding object like a rock the same distance away and use that as your focus point.

When following a paddler through a big water or up-close shot, choose the furthest outside AF sensor that will put the paddler moving into the frame, and then hold down the AF-ON button and keep the sensor over the paddler as they move past. Use this same strategy for panning (see below).

If your camera has focus tracking with lock-on, set the delay to normal or longer so waves or objects passing by in the foreground don’t distract the AF.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

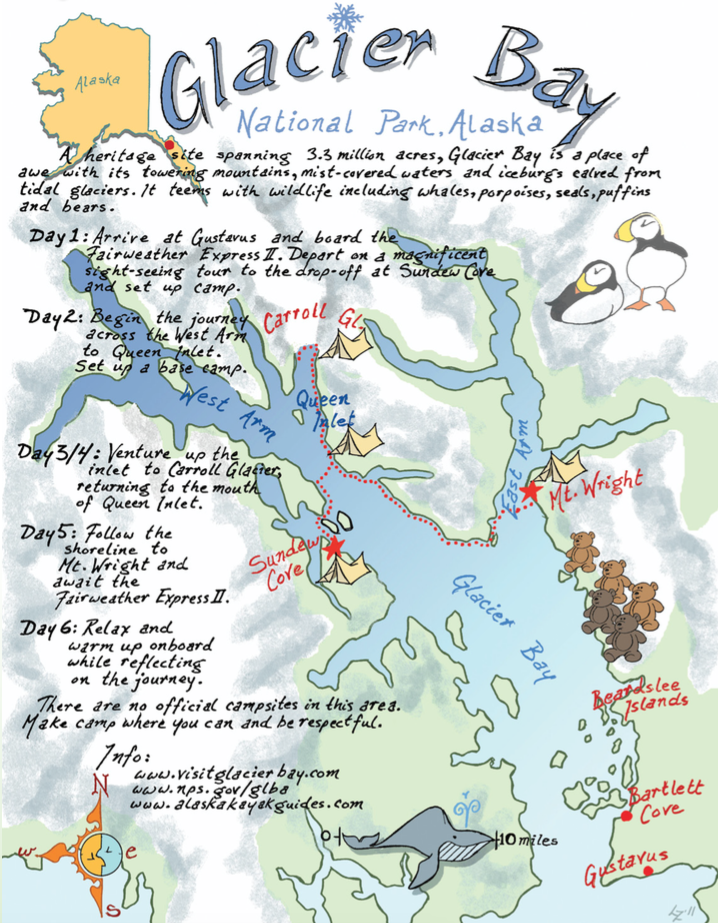

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions