By 1690, Europeans no longer relied on aboriginal traders bringing their furs to Quebec. They had traveled west from Montreal, the epicenter of trade, and entered the wilderness to live and work with the natives, establishing trading posts. As a result, the fur trade boomed.

To accommodate the flow of goods, the Hudson Bay Company (HBCo) commissioned the building of Montreal canoes. Handmade in Louis Maître’s shop in Trois Rivière, the canoes were 30 to 36 feet long, six feet wide and weighed more than 700 pounds. Able to carry four tons of trade goods, they could hold passengers and even livestock. Paddled by the Voyageurs, these canoes plied the big waters from the St Lawrence Seaway to the western shore of Lake Superior, delivering and receiving goods from major trading posts.

Exploring the waterways further west required smaller boats. Looking to compete and carve out its own territory, the North West Company (NWCo) built freight canoes with half the load capacity of the Montreal canoe.

Built by local First Nations men employed by the NWCo, these birch bark canoes were called North Canoes. They were 25 feet long, light enough to be portaged by two paddlers and able to carry two tons. Unlike the Montreal canoe, North Canoes were nimble enough to paddle up and down small rivers. The NWCo paddled them across the continent to the Pacific and Arctic oceans. Those paddlers were the first to trade with uncontacted First Nations communities on the west coast and Canada’s northern territories.

Four to eight paddlers, collectively known as Winterers, manned each North Canoe. Many considered themselves a tougher and more wilderness-savvy breed of trader than the Voyageurs who didn’t often overwinter in the First Nations communities.

By 1821, the HBCo and NWCo ceased their ruthless competition by merging under the Hudson’s Bay name. For another eight decades, annual brigades of North Canoes carried furs to James Bay and brought back trade goods for posts near the height of land, such as Grand Portage and Northern Ontario’s Temiscamingue.

The big Montreal canoe continued to serve the Great Lakes until 1858. The construction of the canals on the Great Lakes, the introduction of steamboats on the Ottawa River in 1851, and finally, the completion of the railroad to Mattawa in 1881, were nails in the coffin of the freighter canoe, rendered slow and old-fashioned.

This photo depicts one of the last North Canoe brigades, seen in the Temagami area in 1902. The local fort closed shortly after and the remaining canoes fell into personal ownership. A few still survive in the historical collections of heritage sites, including former fur trading posts Fort William and Grand Portage.

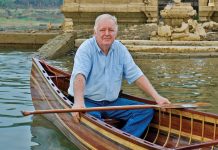

Paddling historian, Wally Schaber, is currently writing a book about the history of the Dumoine River watershed. www.dumoinewatershed.blogspot.com.

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots Early Summer 2014. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots Early Summer 2014. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.