Trips to the wilderness are supposed to revitalize us. That’s why they call it re-creation. So why, after a week of paddling, do I feel so restless and irritable the moment the trip is over?

I’m not the first adventure-seeker afflicted by wicked post-trip hangovers. Paul Caffyn described a similar depression after he kayaked around Japan in 1985. “The worst side of sea kayaking for me was the immediate period following a successful trip,” he noted. “It was not one of elation and satisfaction, as you might expect.” Instead, Caffyn’s sudden lack of purpose left him feeling adrift.

I’ve even suffered from hangovers following weekend-long trips. After two or three days of steady exercise, nature and simple rhythms, I walk through my front door and quickly feel overwhelmed. I’m simultaneously trying to return to the outdoors, catch up with friends, clean my gear and read email. It’s a potent cocktail of regret, frenetic activity and fatigue.

Re-entry is abrupt. I remember talking with a paddler who finally arrived home after 1,500 miles and months away. Shifting his mindset from monitoring the tides to tracking the flood and ebb of Seattle traffic, he said, was the hardest transition of his life.

In the wilds, we return to our hard-wired evolutionary origins: small bands of nomads wandering an ecological landscape. In my kayak, I’m doing what our ancestors did on the plains of Africa. Of course checking email feels weird.

Pulling up to that last beach also adds social disruption. We’re suddenly among people who haven’t shared our experience. As a kid growing up near Manhattan, I returned from my first backpacking trip to the Rockies exploding with stories of jagged peaks, steep alpine passes, cobalt blue lakes and snow in July. The kids on the block weren’t impressed—they had their own experiences hanging out in the neighborhood. While you’re adventuring, others are simply getting on with their lives.

Snow specialist Matthew Sturm, veteran of Arctic science expeditions, describes returning from the Far North in blunt terms: “Your place has been filled like water smoothing the surface of a pond…returning from an expedition is a chance to see how little your world would change if you died.”

Transformational experiences matter to the people who have them, but are puzzling to everyone else. That’s why outdoor adventurers are so tribal: we seek people who understand our experiences even if we haven’t had them together.

The cure for a trip hangover probably isn’t longer or more frequent trips. Most of us struggle to clear decks for a two-week vacation—turning ourselves and our families into Kerouacian wilderness vagabonds isn’t likely. If we can’t spend more time in the wilds, we have to figure out how to keep the simplicity and clarity of the wilds with us when we return.

I once had a boss who spent her career studying wildlife. She lived next to a river where animal tracks and birdsongs were part of her daily life. When she moved into an urban condo, she began her day by opening the window and listening for whatever birds were singing. She kept a journal of nature observations as detailed as the one she’d kept by the river.

My own ritual is sitting on my front porch in the morning with a cup of coffee, regardless of weather, simply to feel the outside air. It’s not the same as coffee on a remote beach days’ paddling from another soul, but I find it helps. Trip hangover is a kind of heartache, and as Stephen Stills sang: If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.

Neil Schulman celebrates kayaking’s diverse heritage in Reflections.

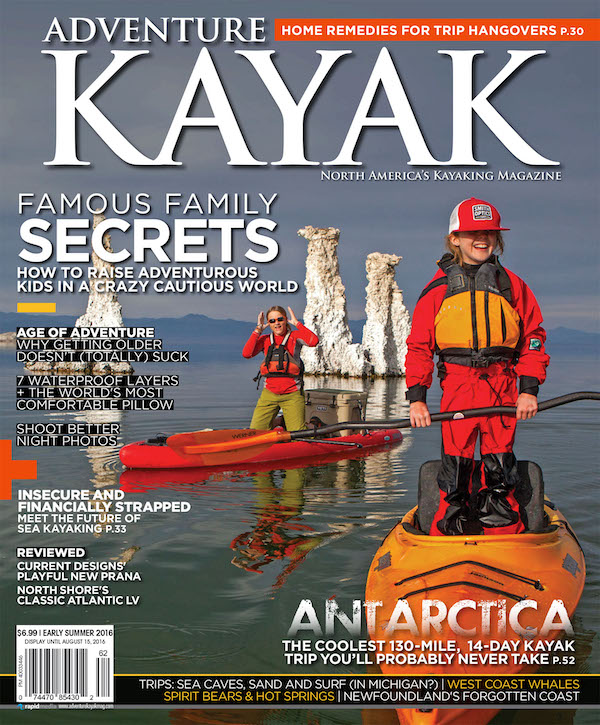

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak Early Summer 2016 issue.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak Early Summer 2016 issue.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.