My first real rain suit came from the sports section of a discount department store. It was heavy, made of a rubberized cotton-nylon blend and camo-colored for stealth in the deep woods. Just 10 years old, I wore it proudly—around the house, in the shower and prancing in my sunny backyard, sweating like a pig and wishing for rain.

Back in those days, a rectangle of that same material served as a groundsheet. When laid inside a floorless Egyptian cotton tent, it was all that was between the dirt and me during overnight outings on the land and water trails of my youth.

The following morning, everything I owned—the Gordie Howe autographed sleeping bag from the Eaton’s catalogue, extra socks and underwear—was rolled up. It was tied with the greatest of care inside that same groundsheet in what my Boy Scout leader optimistically called a waterproofed camp kit.

By comparison, nowadays I’m camping in luxury. My über expensive, Fairy Breath Blue designer rain gear weighs less than the little pouch my childhood suit of armor came in. Stuff sacks and sealed river bags and backpacks ensure everything else stays dry. There’s a fat foam camp bed between me and the cold, hard ground. Maps and compasses used to dictate navigation; now I have photovoltaic blankets covering my loaded canoe, charging the gizmos that keep me on course as I paddle.

Wilderness gear has changed a lot in the last 50 years, and even more in the 50 years before that. Our camp kits look nothing like those of the original adventurers, the Voyageurs, who ventured forth with just the clothes on their backs, canvas tarps and tumplines. They used packs without straps, let alone suspension systems, and traveled hundreds of miles with hand-drawn maps, if they had maps at all. Imagine that!

Of course, Mackenzie basin explorer George Douglas had far more advanced gear than the Voyageurs when he was exploring in the early 20th century. My dad’s generation had even more than him and, like his dad before him, my dad would look at my Scout’s gear and scoff—“That’s not real camping!”

But I disagree. As a kid, wearing that rubber rain suit and smelling like a wet dog in neoprene, I ventured into the depths of the forests and river routes near my home. I imagined I was John Rae, Edmund Hillary, Roald Amundsen or Robert Falcon Scott, exploring the wilds, climbing the peaks and racing toward the poles.

It wasn’t my ragamuffin kit that connected me to these timeless adventurers—though I imagine theirs must have smelled similarly— it was the act of exploration and discovery, full of real route finding, real risk and real adventure. In this sense, nothing has changed. Whether navigating by starlight, compass or GPS, we’re all explorers here.

I went to the woods, even in the very early days, to feel the rain on my face and to see if I had what was needed to meet the challenges the trip might present. And what I learned on the trail—about myself and others, about life and the natural world—through triumph and the occasional disaster, was something I could bring home and apply to the challenges of everyday life.

That desire has always led us into the woods, throughout the ages, in spite of what we own.

Columnist James Raffan is the Director of Development at the Canadian Canoe Museum.

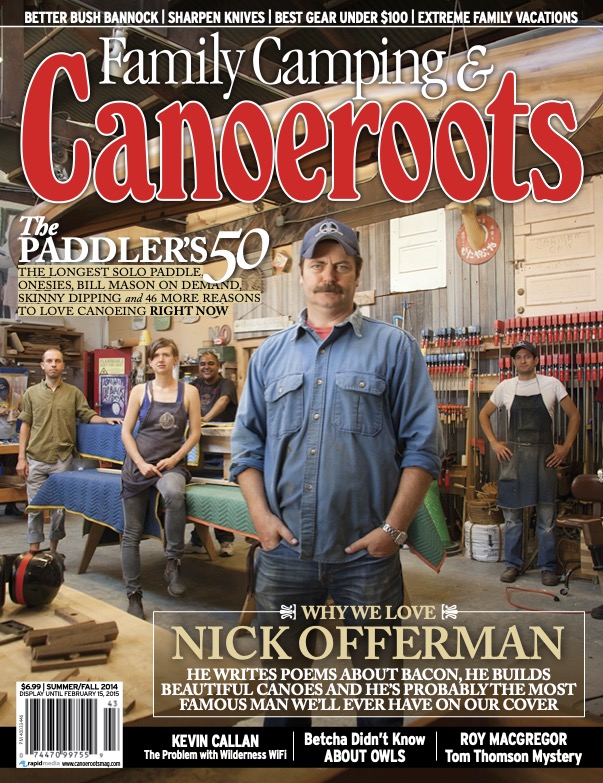

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots and Family Camping, Summer/Fall 2014. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots and Family Camping, Summer/Fall 2014. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.