We live in a time where multitasking is king. Job postings call for applicants who can skillfully handle many duties at once. Families eat breakfast together while scrolling through photos on their phones, periodically tuning into the conversation. We answer emails while chatting on speakerphone and sneaking in a sandwich, all in the name of productivity. We are at the mercy of the notifications, pings and vibrations emanating from our numerous devices. The ability to manage many thoughts and ideas at once is seen as an asset, although there is mounting evidence to the contrary.

In their 2011 study “Juggling on a high wire: Multitasking effects on performance,” Rachel F. Adler and Raquel Benbunan-Fich found that while some multitasking improves productivity, too much has a negative effect. When performance is measured in terms of accuracy, the negative effects of multitasking are especially pronounced.

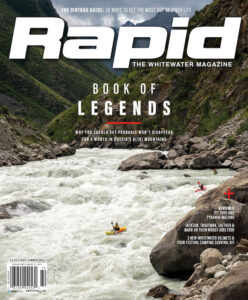

Rivers have no patience for mulitaskers. Experiencing the features they have to offer requires concentration, focus and a relinquishing of unrelated thoughts, worries and catwheeling attention spans. Sharp ledges and retentive holes demand to be the sole focus. It’s like skiing powdery slopes coated in tight trees, leaning into greasy switchback turns on a mountain bike trail or problem-solving an incredibly technical climbing route.

Last spring I went to a whitewater festival on a new river. It was dam controlled and the single release each year brought paddlers from hundreds of miles away to camp in an idyllic mint-green field where the river melted into a deep lake.

I’d just begun a new job and felt perpetually frazzled, always convinced I’d left some key detail unattended or forgotten to respond to an important email. During the two-day festival, the challenges of the river I faced during five-hour day runs were all I could think about. My obsession was how to navigate tricky holes and catch those crucial can’t-miss eddies. Driving home Sunday night through tiny riverside towns, my relaxed mental state indicated I had enjoyed a reprieve from rumination that weekend, but I wasn’t quite sure why.

After shooting photos of a new whitewater canoe with some other members of the Rapid team on a -5-degree Celsius January afternoon on our backyard river, we stood around the take-out. In between shedding helmets, reaching for beanies and clawing at gaskets with numb fingers, someone mentioned they felt way better than they had before paddling. Paddling the short section of whitewater ringed by sheets of ice required her to completely cease thinking about other things. In an unlikely place— the bow of a canoe in a rapid—she relaxed.

You don’t have the luxury of thinking about other things in whitewater. Maybe that is the luxury.

Hannah Griffin is a journalist, photographer, and mountain lover. She’s a NYU Journalism alum, and her work has appeared in The Guardian, Al Jazeera and Vice.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Early Summer 2017 issue.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Early Summer 2017 issue.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.