I couldn’t even begin to guess who figured this out first. I grew up on a farm, and it never occurred to me while milking cows and baling hay. Nor as a rookie raft guide doing day trips did it ever get mentioned. But after I talked my way into a multi-day guide job on Utah’s Canyonlands’ rivers it was—I was told in no uncertain terms—absolutely essential every night I slather my feet and hands in cow’s udder salve. Bag Balm to be exact.

Yeah, right, I thought. A joke on the new guy.

No joke. That’s what you do, and it works.

This is how it goes with the essentials. Sometimes we figure these things out for ourselves, but with river guiding’s ingrained mentor model, these things are often passed on from senior guides to the new ones.

The greatest river running essential no one talks about

1  Bag Balm

Bag Balm

A trip to Intermountain Farm Supply—then the only place to get Bag Balm, though the word has now gotten out and now you can find it more easily—for a one-pound tin of medicated cream meant for cows’ udders. It has some magical qualities to deal with hands blistered from the oars and feet cracked from the endless wet-dry cycle. It is essential for river guides. A tin rode in the bottom of my drybag for many years.

2  Nail clippers

Nail clippers

I didn’t think much about my fingernails until I became a guide. And then it became crucial they were as short as possible at all times. Guides carry nail clippers in their life vest pocket.

Most rowing guides hold the oars thumb on end, rather than wrapped under. This means thumbs almost touch as they pass by each other a thousand times a day. Any nail showing means a bloody gouge on the opposing thumb if a stroke gets duffed. Likewise, long toenails get unceremoniously ripped off under cross tubes or when stepped on by clients. Best avoided.

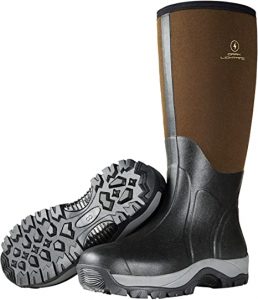

3  Rubber boots

Rubber boots

Before my first rip as a northern canoe guide in the Yukon, my trip leader took me to Canadian Tire in Whitehorse to buy a pair. Growing up on a farm, I wore rubber boots sometimes, but for canoe guides, they are essential.

That same trip leader directed me not to buy just any rubber boot, but the one with a liner, so it can be pulled out to dry at night, and a nylon cuff. She went on to show me how to replace the cuff lace with bungee and a cord-lock, making them pretty much soaker proof. Essential.

4 Channel lock pliers

I could also tell you about channel lock pliers, a frame wrench, or butane lighters—all also essential. But for me, it’s not so much about the essentials themselves. Many have their own personally approved packing list, or you can Google a generic list at a moment’s notice.

The real story is the people who introduced them to me. It’s the guide-vine passing on this knowledge and the mentor relationships found in every guide team. Sometimes these essentials are passed on with genuine caring, other times with impatience and an undertone of “How can you not know this?”

I remember these mentors, and owe them all a nod every time I have a frame wrench at my fingertips when an oar stand slips; every time I replace the laces in a new pair of rubber boots (or step in over the tops and get away scot-free!); and every night as I massage cow udder salve into my feet.

I appreciate those who have come before me and took the time to pass on the little pieces of their hard-earned expertise—perhaps passed down to them by their mentors. Another essential.

Tools in my pocket and pieces of gear come and go, but a mentor’s impact is everlasting.

Jeff Jackson is a risk management professor at Algonquin College, on the banks of the Ottawa River.

The best memories come from bad ideas done with good friends. | Photo: Robert Faubert

Bag Balm

Bag Balm Nail clippers

Nail clippers Rubber boots

Rubber boots