In the austral summer of 2013, four adventurous paddlers, photographers and filmmakers caught a 14-hour flight from the Pacific Northwest, bought a secondhand camper van, loaded kayaks and gear, and set out to explore the island’s rich paddling culture.

Stewart Island Is Land of the Glowing Skies

Thick, low clouds sailed swiftly across a restless sky. A gust of wind snatched an empty dry bag and sent it tumbling down the sloping, sandy beach at Halfmoon Bay. As I snagged it, I caught Cynthia’s gaze. She flashed a quick smile but her eyes looked more reserved. With 45-knot winds and heavy storms forecasted, we were feeling pressured to get on the water and move quickly to find a safe place to camp for the night.

The beginning of an adventure, like the opening of a new book, has a ceremonial nature. A story is about to be released, pulled from time and its environment. Add to that existential reflection a remote, exotic location with a building storm and it’s a great recipe for excitement.

As we traveled to the bottom of the South Island with kayaks on top of our van, people approached to ask where we were headed. When we replied, “Stewart Island,” their eyes grew large and their heads nodded in approval. One man exclaimed, “Stewart Island? Most Kiwis [local New Zealanders] don’t even make it there!” Those who had visited spoke of the moody weather, untouched beauty and lack of invasive species. Rakiura National Park, which constitutes over 80 percent of the island, is home to a number of endangered birds including the yellow-eyed penguin, the kakapo (a parrot that is slowly rebounding from the brink of extinction) and the elusive, flightless kiwi.

The total population of the 674-square-mile island is a mere 381, all concentrated in the single town of Oban, where the ferry arrives after crossing the notoriously treacherous waters of Foveaux Strait. While it takes some intention to get there and storms are common in the Roaring 40s—Stewart lies between latitudes 46 and 47 degrees south—the undisturbed nature of the bush, abundant seafood (a bag of rice would suffice for trip supplies) and lack of tourists make it an outstanding paddling destination.

It is often under such suspenseful moments that life tends to throw a curve ball. A missing bulkhead for one of the folding kayaks we had brought with us sent Freya bounding off to the local pub while I stood behind questioning what the pub could possibly offer, other than a calming ginger beer.

Moments later I was ushered into a van with Liz, daughter of the pub owner and an avid kayaker. It turned out she and her husband were selling the kayak rental shop they ran to focus on raising their young children. Since the kayaks were sitting unused, she explained, we might as well borrow one.

Watching the building whitecaps, we discussed how to harvest and prepare paua (New Zealand abalone) and chatted about life on the island. “The beauty is spectacular,” Liz told me, “but the weather is a bit shifty.”

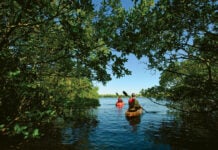

Fifty-knot winds sent us hurrying back to Liz’s boathouse soon after launching, but the following day we were able to make our way to Miller’s Beach, a beautiful yellow sand bay. From there we crossed Paterson Inlet and paddled into the southwest arm, picking our way through a maze of sandbars to the mouth of the Rakeahua River. Tea trees and spiky flax swords lined the banks of the dark, tannin-infused Rakeahua. A chorus of bellbirds sang to us as we made our way up the increasingly narrow river to a cozy Department of Conservation hut outfitted with bunks, rainwater catchment and a small woodstove.

We gorged ourselves on the lush intertidal zones of the inlet, eating the rich black meat of paua harvested by scooping with kayak paddles, briny mussels plucked from exposed rocks and fresh blue cod Jaime caught on his handline.

At night we grabbed headlamps and scanned the bush for the nocturnal kiwi. Stewart Island’s Maori name—Rakiura, or land of the glowing skies—is usually attributed to the Aurora Australis that sometimes paint the skies at night, but the dark rain clouds contrasting with bright, teasing patches of cyan made the epithet seem just as appropriate during the day.

Our fifth and final day of paddling ended back at the pub, where we caught wind of Phil Dove who, with his wife Annett, operates a paradisiacal ocean view lodge and the only remaining kayak outfitter on Stewart Island. Like most of the folks we met on the island, he was generous and full of entertaining stories. Phil is also a well-rounded whitewater paddler and sea kayaker, an unusual combination back home in the States, where the two sports are both culturally and geographically divided. His tales ranged from recounting his solo circumnavigation of Stewart to losing all his gear—and clothes!—in a swim through the North Island’s infamous Nevis Bluff rapid.

In New Zealand, where mountain rivers spill directly into the sea, many paddlers are lured by both fresh water and salty surf, blurring the lines between whitewater and sea kayaking.

If You Go to Stewart Island

Stewart Island is a remote and logistically challenging place to paddle. Bring your own kayak over on the ferry from Bluff or contact Phil’s Sea Kayak (www.observationrocklodge.co.nz) to arrange a half-day, day or longer trip out of Paterson Inlet. The quiet blackwater rivers at the west end of the inlet are a highlight. Be sure to check a tide table and weather update before heading out.

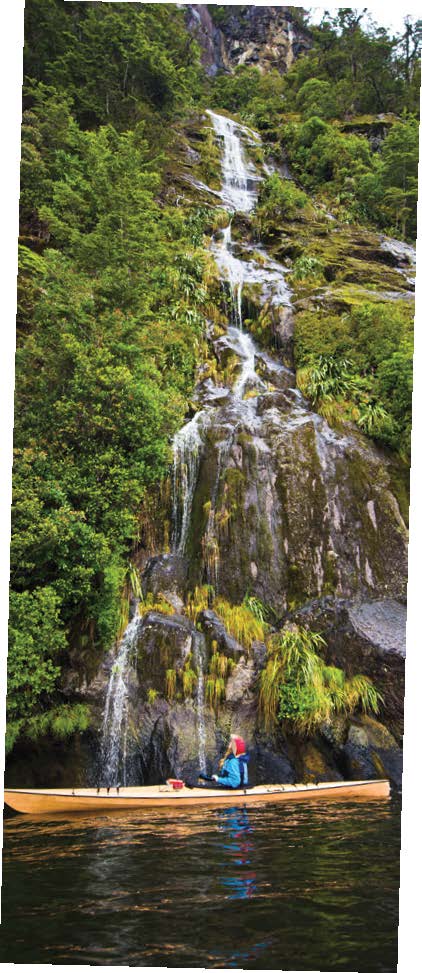

Milford Sound Is Crown Jewel of Fiordland

Dramatic glacier-carved cliffs that soar 4,000 feet straight up from the sea and thousands of breathtaking waterfalls that appear like magical faucets after the frequent rains have made this spectacular fiord one of the most popular tourist destinations on the South Island.

We pulled into Milford Sound on the evening of a gathering. I mistakenly called it a “party,” but was quickly corrected by one of our hosts: “Parties in Milford are when people dance naked on the tables.” Nevertheless, everyone in town was in attendance, including the local fishermen, skippers, guides and cruise boat staff.

Jaime had lined up an interview with the founder of New Zealand’s longest established owner-operated sea kayak company: the famous Rosco of Rosco’s Milford Kayaks, who also happened to be hosting the gathering.

Rosco Gaudin first saw Milford Sound’s potential as a world-class paddling destination in 1988, when he paddled into the fiord on a trip with friends and found himself escorted by a pod of 30 bottlenose dolphins. The experience planted the seed for the area’s first commercial sea kayaking operation, which Rosco has kept small and is still happily helming over two decades later. “I feel extremely privileged to be living my life in an area I love,” he says, “It’s not just the paddling, it is the lifestyle, the people, the vibe and the buzz of showing everyone our playground in paradise.”

Rosco is also the self-proclaimed Mayor of Milford (no one contests the title) and something of a local celebrity. For the past 12 years, he has organized The Great Annual Nude Tunnel Run, which it turns out, is exactly as it sounds.

Every April 1st, around 100 participants run naked—save for headlamps and tennis shoes—through the Homer Tunnel, a nearly mile-long passage that was hand-dug through the mountainside between 1935 and 1953 to provide road access to Milford. The prizes are meager—the fastest woman and man have their names engraved into a nude Barbie and Ken doll, respectively—but entry fees are donated to charity and, as Rosco points out, there are other rewards: “Being naked is invigorating, natural and beautiful; it’s a great way to make new friends.”

The next day we joined one of Rosco’s guides, Mark Buckland, on a tour of the fiord. We were shuttled by motorboat to just shy of the Tasman Sea, where we hopped in kayaks and paddled the 10 miles back through the steep-sided fiord to the village of Milford. Along the way, we admired 500-foot Sterling Falls and paddled with a pod of playful bottlenose dolphins that leapt into the air all around us.

Every paddler we met in Milford expressed gratitude for being able to spend time in such an amazing place. Of all the stories we heard, one in particular stuck with me: a Maori legend about the origin of Fiordland’s pesky, omnipresent sandflies. In Maori culture, the biting insects were born at Sandfly Point, near today’s kayak launch, to protect Milford Sound from the careless destruction that people often bring to beautiful places.

If You Go…

The knowledgeable staff at Rosco’s Milford Kayaks (www.roscosmilfordkayaks.com) offer daily trips for all levels of paddlers. Options include taking a water taxi to the mouth of Milford Sound and paddling back, sunset and sunrise tours, or combining kayaking with hiking part of the renowned Milford Track—hailed as “the finest walk in the world.” Whichever you choose, don’t forget your bug repellant.

The West Coast Is Home of Paddling Legends

Sparsely

populated and generally inhospitable, the West Coast challenges surf kayakers and advanced paddlers. Here, the Southern Alps, the 10,000–12,000-foot spine of the South Island, meet the pounding swell of the Tasman Sea and winds blow with unobstructed fury all the way from Australia. It is a coast of contrasts, glaciers reach into lush rainforest and turquoise rivers tumble quickly to the sea.

Fittingly, the region is also home to two of the country’s best known paddling legends: Paul Caffyn and Mick Hopkinson, the godfathers of New Zealand sea kayaking and whitewater paddling, respectively.

It’s hard to summarize Paul Caffyn’s many astonishing achievements, but most paddlers will recognize him as the first person to paddle around New Zealand, Australia, Great Britain, Japan and coastal Alaska, to name a few. He’s traveled over 23,000 miles by kayak. He is, in short, sea kayaking’s Sir Edmund Hillary.

He is also a casual, unassuming man who welcomes us into his modest home, appropriately perched 20 precarious feet above the sea. One rogue wave could easily flood his living room. When someone points this out, Caffyn casually sips his tea, staring out the sliding glass door into the choppy seas, and tells us that slowly the waves have indeed nibbled away at the cliff just beyond his back door. He seems to need the rhythm of the sea nearby, like a moth drawn to light. Books, opera posters, old photographs and paddling keepsakes crowd the walls of his home. I scan them, looking for clues as to the man behind the legend.

When we ask about his adventures, Caffyn smiles and corrects us, “I subscribe to the belief that adventure is what happens when things go wrong.”

His goal has always been to mitigate adventure and one of his favorite aspects of such massive undertakings as circumnavigating a continent is the planning and challenge of the logistics. I begin to see a calculated, reflective man who is comfortable by himself and at home on the sea.

From Caffyn’s house we head north to Murchison, home of the New Zealand Kayak School, founded and owned by whitewater legend Mick Hopkinson. Mick’s first descents include Africa’s Blue Nile, Everest’s Dudh Khosi and many other rivers in Pakistan, Switzerland, Austria and New Zealand. He’s been inducted into the International Whitewater Hall of Fame and his school has earned international acclaim.

Piquant and just a little sardonic, Mick likes people who stay on their toes, not surprising for a man who loves linking moves in rough water. Now 65, he tells us he is considering taking up sea kayaking in his eighties. Teasing aside, Mick is a gracious host who cares deeply about the waters he paddles.

Mick started his career as a slalom paddler in Britain, where it was illegal to kayak local rivers. Fishermen and farmers threw rocks at paddlers for trespassing, and slalom races provided his only opportunity to access the water.

Mick later fell in love with the free-flowing rivers of New Zealand and stayed. As he talks passionately about the future of his adopted country’s rivers and the “idiots” who want to dam them, I get the sense that he and Edward Abbey would have enjoyed sharing a beer. When I bring up the notoriously intractable author and polemic conservationist’s name, Mick smiles broadly and picks up a page tacked above his desk.

“One final paragraph of advice: do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am—a reluctant enthusiast… a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of yourselves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it’s still here…” he reads the quote in its entirety and smiles again. “I’m really just a hedonist, turned conservationist so others can be hedonists.”

If You Go To The West Coast

Take a class or rent whitewater equipment at Mick’s New Zealand Kayak School (www.nzkayakschool.com). Even if you’ve never paddled a river before, the school’s world-class staff teaches all skill levels from October through April. They can also organize helicopter shuttles to many of the West Coast’s remote access rivers.

Abel Tasman – Sun and Sand at the Top of the South

The perfect antithesis to the wet and rugged coasts found further south, Abel Tasman’s golden sand beaches, sun-filled fruit orchards and warm, Caribbean-blue water make it a paddling paradise. Although it’s consequentially more commercialized, the region is also rich in history and Maori culture.

We link up with Kyle Mulinder, a charismatic guide for the Sea Kayak Company who takes great pride in his Maori heritage and carries on tour his grandmother’s conch, or putatara. The shell is a traditional Taonga puoro, Maori musical instruments used in the recounting of creation stores. Mulinder shares some of these stories, enacting each tale as he tells it, dancing and drawing in the sand in front of his international audience: a couple from Germany, two girls from France, two Americans and two Kiwis.

He relates his own speculations on history and what first contact must have been like for the Maori—indigenous Polynesians whom it is believed traveled over 2,500 miles to New Zealand by dug-out canoes, or waka, and settled some 400 years before the first Europeans—when Dutch explorer Abel Tasman sailed into nearby Golden Bay in 1642. Although Tasman is credited with “discovering” New Zealand, he and his crew actually never set foot on the island. When the Dutch sailors attempted to land in the bay, a major agricultural area for the Maori, they were met by a fleet of war canoes. Four of Tasman’s men were killed in a bloody skirmish and the explorer hastily sailed away, never to return.

After our tour with Mulinder, we paddle to the far end of Abel Tasman National Park and pick our way back over 30 miles along the shore for the next three days. It’s a leisurely trip compared to our initial adventure on Stewart Island. The skies are clear and the sun so powerful that unshielded skin burns in minutes. We seize the opportunity to paddle in the cool mornings and linger at offshore island fur seal nurseries, watching the curious pups play in the clear water. Water taxis buzz up and down the coast throughout the day, but in the quiet evenings we share well-equipped campsites and swap stories with other kayakers and hikers from around the world.

If You Go to Abel Tasman

Water taxis make it possible to shuttle into Abel Tasman National Park from the villages of Marahau or Kaiteriteri, then paddle back. Allow one day from Anchorage Bay, or three days from Separation Point at the park’s north end. Another popular option combines paddling out and hiking back on the Abel Tasman Coast Track. Arrange rentals or a guided tour with the Sea Kayak Company (www.seakayaknz.co.nz).

This article first appeared in the Summer 2014 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.