Last summer, four-time freestyle world champion and whitewater paddling legend Eric Jackson took up training for a new discipline. He was eyeing a spot on the U.S. extreme slalom team.

Jackson trained with his 28-year-old son, Dane, ahead of trials. Part of their training was head-to-head paddling on flatwater. In most cases, Jackson was as fast or faster than his son.

At 58, he’s now the oldest member of the U.S. national team after qualifying for the newly-added extreme slalom event. People keep asking him if he’ll retire.

“Why would you want to retire if you’re having fun doing it,” Jackson says.

The questions kept coming. Wasn’t he finding it harder to recover? Not really. He started paying more attention to who was asking the questions. “They weren’t working out,” he says. “They weren’t athletes anymore.”

Why you’re never too old to be whitewater world champion

From running whitewater to honing their skills on the slalom course, kayakers flock to the sport for many reasons. But what keeps them on the river is a never-ending supply of fun, challenge and life-long learning. And as long as your skills remain sharp, you can compete at a high-performance level for decades.

At what age are high-performance whitewater paddlers typically peaking? There isn’t much scientific data about whitewater kayaking, but we can look to the sport’s Olympic discipline for some clues. In a 2016 paper, researchers analyzed the ages of top performers in 40 sports at the 2012 London Olympics. The top 10 athletes in canoeing, which didn’t separate flatwater and whitewater events, had an average age of 27.5 for women and 27.8 for men. The youngest solo athlete was Australia’s Jessica Fox, 18, who took home silver in women’s K-1, while the oldest athlete on the podium was 34-year-old Tony Estanguet of France, who won gold in men’s C-1 slalom.

Swimmers, in contrast, peak in their early 20s. Gymnasts, divers and BMX cyclists—all sports requiring flexibility and acrobatics, like freestyle kayaking—also peak in their early 20s, according to the same research.

The enduring allure of kayaking

You don’t want to do most sports forever, according to Jackson, who grew up as a competitive swimmer. “Do you want to swim back and forth in a chlorinated pool looking at a black line and then when you get to the T on the other side, you turn around and return and just do it over and over for 50 years, 40 years, 30 years,” he says. “You want to do it to prove you can be the best, then you get there and it’s like, man, wouldn’t I love to go kayaking or skiing and do something fun.”

There are many reasons why athletes choose to leave high-performance sport: career, marriage, kids and injury are the most common. Why they stay is clear, especially if they’re able to organize their lives around paddling. Jackson traveled between rivers with his young family in a giant RV, while two-time extreme kayaking world champion Mariann Saether follows the paddling season south with her family. They split their time between the road, their home in Norway and their riverside home in Chile.

“I never get bored in my kayak,” says Saether, who learned to paddle more than 25 years ago. Now 41, Saether won her world titles at age 35 and 39. While she participated in a whirlwind of activities growing up in Norway, kayaking has her heart.

“I got pretty good on a snowboard, [at] handball, I even did synchronized swimming and baton-twirling,” she adds. “It all got boring. But out on the river, I am never bored.”

Older athletes must adapt to compete

David Ford made the Canadian whitewater slalom team for the first time in 1984. Thirty-three years later, he qualified for his final national team in 2017 at age 50.

Ford is a five-time Olympian and in 1999, at age 32, became the first non-European paddler to win a men’s K1 title at a slalom world championship.

He loved being on the water, training and the puzzle of high performance: what pieces can you add and subtract to give you an edge? As he got older, those pieces changed, and he gained access to great minds in sports medicine. They recommended more rest and recovery, and phasing his training to peak precisely when he needed to.

Ford has always been quick to adapt to the shifting sport of whitewater slalom, and he credits the ability to change for allowing him to remain competitive for so long. Even as boats got shorter and courses tightened, he remained one of the top male slalom kayakers in the country, in its deepest field. “The key has been to just not stop moving,” he told one reporter ahead of his final world championship in 2017.

But toward the end of Ford’s competitive slalom career, the kids who grew up in the shorter slalom boats were catching up. “They were able to do things I could do, but they were doing it just with instinct,” Ford says. “I had to think about it, and the slight amount of thinking about it just made it tougher.”

While Ford is now retired from slalom paddling, he’s still out on the water at least four times a week.

Veteran squirt boaters stay on top

One discipline that hasn’t seen much growth is squirt boating. The low-volume boat remains a favorite for Canadian freestyle team member Matt Hamilton. He’s currently qualified to represent the country at the next world championships in 2022 and was also part of the squirt boat contingent Canada sent to Spain in 2019, who were all over 30.

There are younger paddlers participating in squirt, says Hamilton, 46. They just aren’t performing as well in competitions. So veteran paddlers like Hamilton, who have more than three decades of experience on the water, continue to compete at world championship levels.

Hamilton, who lives a few minutes from the take-out on the Ottawa River, says he’s putting time in on the water. In 2021, he logged more than 100 days in his boat.

The idea of just putting the time in has served fellow freestyle kayaker Jackson well throughout his career. “If you are an athlete focused on that part of it, the physical side of it,” he says, “and you don’t let it go, you maintain it, it doesn’t just go away.”

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2022 issue of Paddling Magazine. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.

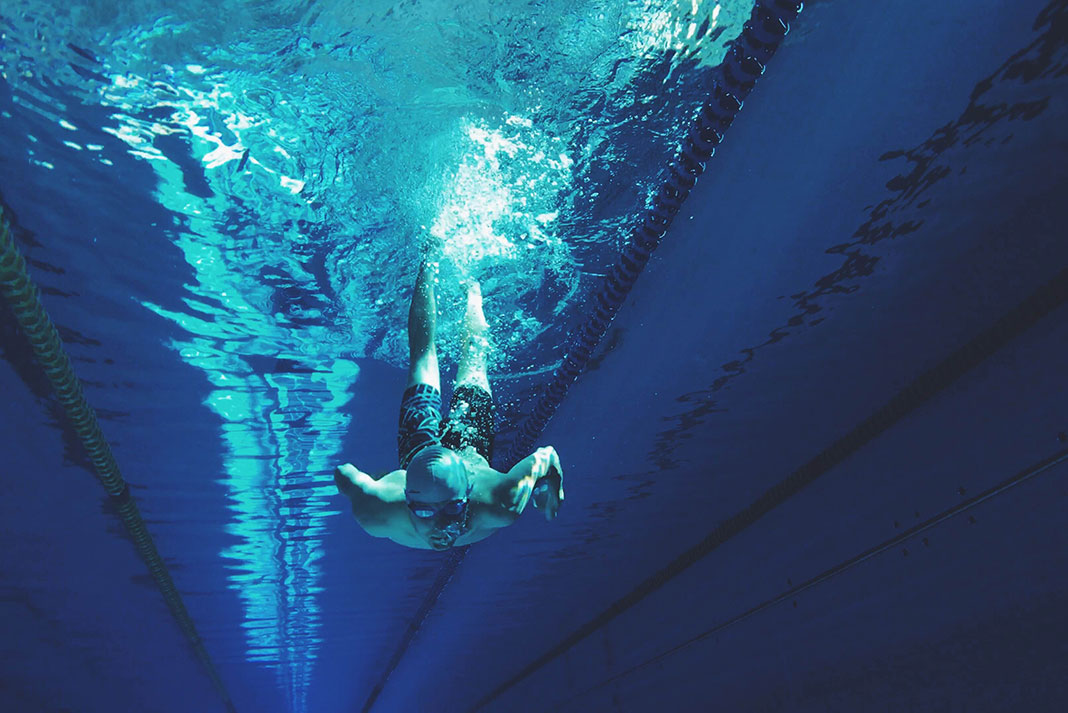

Shine on you crazy diamond. | Feature photo: Peter Holcombe