It seemed 2010 was a year filled with pe troleum-related disaster—the Gulf, Lake Michigan, the Niger delta, the Yellow Sea. Gushing crude made for dramatic headlines, but these stories were as much about water as they were about oil.

In North America, we have 11.5 percent of the world’s renewable freshwater resources. However, our surplus is no excuse for sloppy stewardship or lack of policy governing downstream rights, ownership and access to water.

The Upper Delaware—a designated National Wild and Scenic River—topped American Rivers’ 2010 list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers. This watershed, which provides drinking water for 17 million people in New York and Pennsylvania, is threatened by development of the vast Marcellus Shale natural gas field.

While our understanding of balanced development and conservation continues to expand, as canoeists, so should our awareness and responsibility for our waterways.

With the spike in natural gas prices, the region has the potential to become one of the U.S.’s most lucrative energy deposits. Exploration and extraction come at the cost of surface and groundwater toxicity along with soil and habitat contamination throughout the Upper Delaware catchment.

In northwestern Canada, the Mackenzie River basin rivals the scale of the Amazon and Congo rivers. The Mackenzie is fed by a set of waterways at the epicenter of the largest industrial project on earth, the Alberta tar sands.

Currently, between two and five barrels of water are required for each barrel of oil extracted from the sands. This means the tar sands draw enough water every year to meet the needs of a city of 2.5 million people. Much of that water comes from the Athabasca River, raising concerns of overdrawing the resource.

The release of tailings into the Athabasca and the surrounding groundwater supply further intensifies pressure on the area. Tens of thousands of miles of waterways are affected by this continual contamination of the North’s most significant watershed.

This year marks an opportunity to clean things up. While our understanding of balanced development and conservation continues to expand, as canoeists, so should our awareness and responsibility for our waterways.

When a project like the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) hits a milestone like it has in 2011, it’s worth celebrating. The CHRS program operates under the notion that rivers have shaped our continent and its people. And, under its framework, the people—communities, rec- reational user groups and landowners—are responsible for designating waterways as Heritage Rivers.

So hats off to organizations like American Rivers and programs such as the CHRS for engaging North Americans, keeping us all from being left thirsty for more.

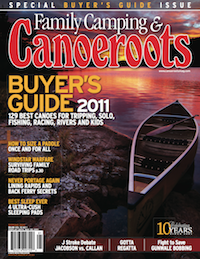

This article first appeared in the Spring 2011 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.