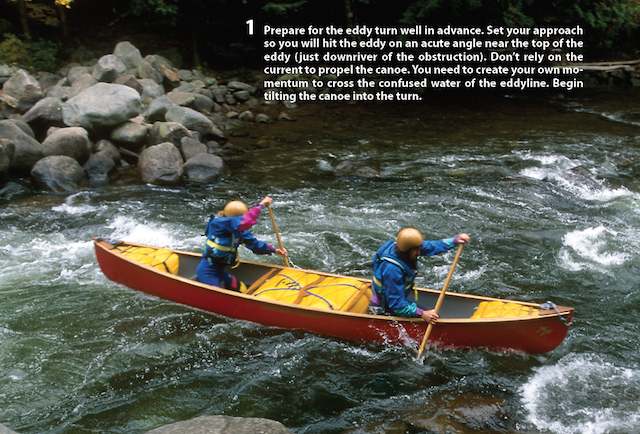

Eddies are sanctuaries of calm water formed behind obstacles that disrupt the flow of fast-moving water. When water hits an obstacle, such as a constricted shoreline or mid-river rock, it must move around it before continuing downstream. This leaves an area behind the obstruction where the water recirculates back upriver.

For canoeists, eddies provide a safe place to stop, rest and scout—or take to the portage—amid even the wildest whitewater. But first you have to break through the eddyline, the dividing line between current moving downstream and the eddy water recirculating behind the obstacle.

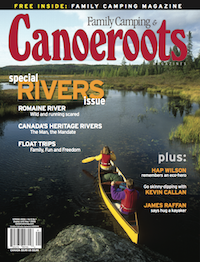

With practice it is easy to identify the boundary between the fast-moving and aerated downstream flow and the calmer, slower water of the eddy. It is important to cross this eddyline with an acute angle of approach. You should carry momentum across the eddyline and time your turn so the contrasting currents help to spin your canoe upstream as you enter the eddy.

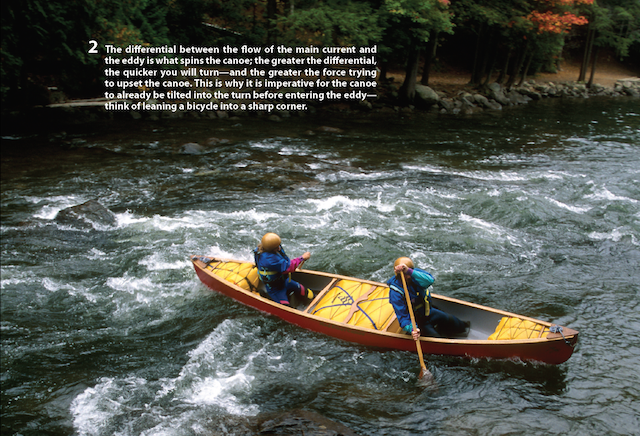

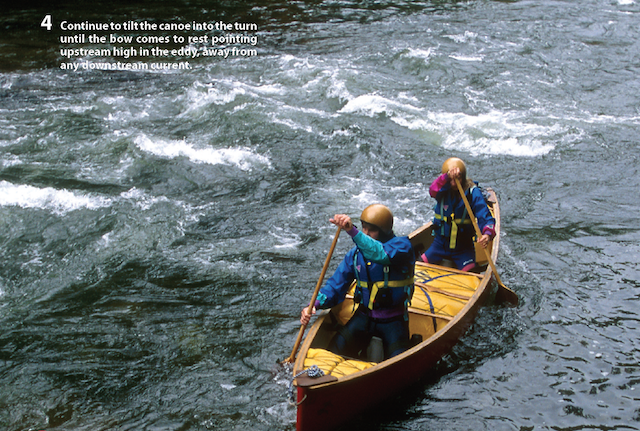

The three components of an eddy turn are: angle—entering the eddy at an angle of between 45 and 90 degrees to the eddyline; motion—carrying speed and momentum into the eddy; and tilt—leaning the canoe into the turn.