Paddling a loaded, two-person canoe doesn’t just have to be an art expose but it is okay for it to be an efficient process as well. I still recall the day when I was first introduced to the sit-and-switch paddling technique. I was trying to cross Churchill Lake on Maine’s Allagash River waterway in a headwind. My bow partner was tiring and I was in the stern, using the traditional J-stroke. Then we heard “hut, hut, hut” coming from behind.

There were four paddlers in two canoes coming fast. They had shorter bent shaft paddles and they were switching sides every 10 strokes. They did not appear to be working hard, but they easily passed us. Two hours later, when we finally reached camp, we found our sit-and-switch friends with their tents already set up. They were fishing!

Learn the sit-and-switch canoe paddling technique

The sit-and-switch method offers more speed and efficiency than the J-stroke. There are less steering corrections to slow momentum, allowing both paddlers to power forward. You don’t have to participate in races to appreciate it. If you’ve ever crossed a big lake, bore into a headwind or just tried to reach that next campsite at the end of a long day, this technique should be in your arsenal.

Getting started

The good news is that the sit-and-switch stroke is not hard to learn.

- Opt for a canoe with comfortable seats. Foot braces are optional but will increase performance.

- Use a bent shaft paddle. It’s more efficient, and the stout blade allows for a faster cadence.

- Adjust any gear you carry to keep the canoe as level as possible.

- Partners paddle on opposite sides, switching every eight to 12 strokes.

- Partners should time their strokes with each other; the bow paddler sets the pace.

- The stern paddler calls the switches by calling “switch” or “hut.”

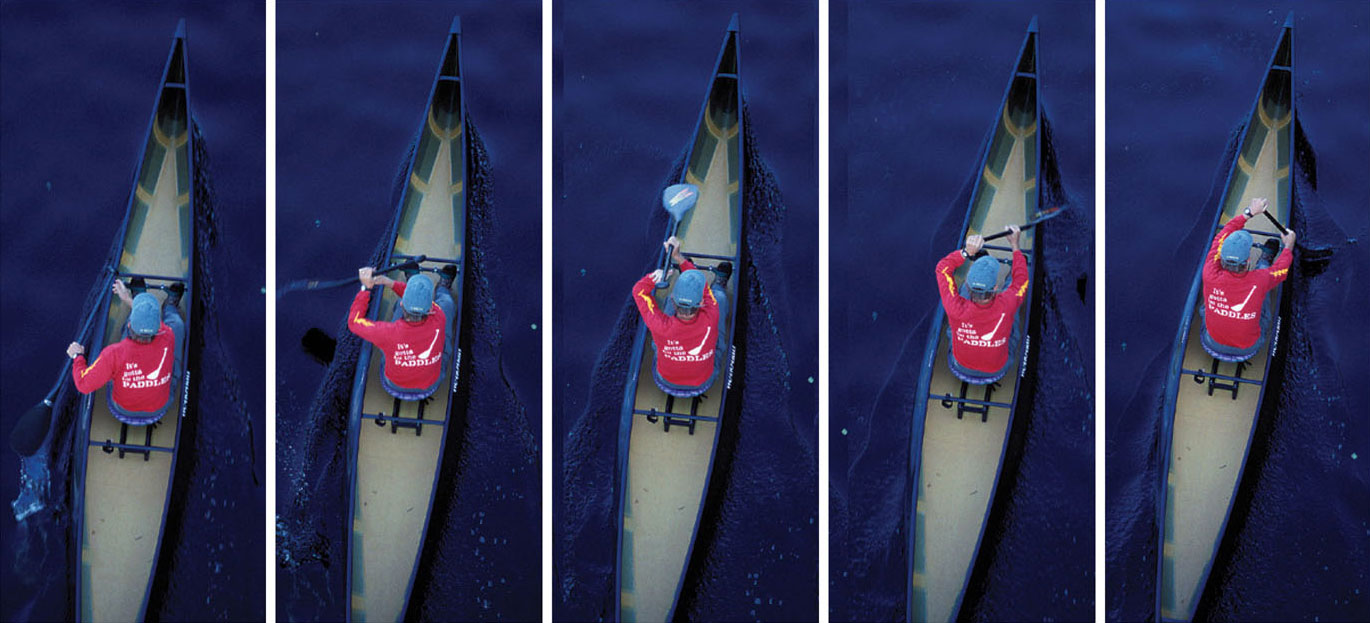

Sit-and-switch stroke basics

Like any good forward stroke, power comes from the major muscle groups of the back, shoulders and torso to pull the canoe through the water.

Getting the paddle in the water and anchoring it is called the “catch.” Bury the blade in the water as early as possible in your stroke by reaching forward with the lower arm and dropping that shoulder as you start the stroke.

Simultaneously, reach up and across with the upper arm, so that the upper hand is directly over the paddle blade, essentially keeping the paddle perpendicular to the water. Let the upper arm flex slightly, and keep the upper hand no higher than the top of your head. As you pull the canoe forward, drive down and slightly forward with the upper arm. Use your arms as levers to get power from your torso and shoulders.

Keep your stroke short. Once the elbow of your lower arm reaches your torso, slip the blade out to the side and reach forward again to begin your next stroke.

Aim to sit nearly erect with a slight forward lean. Do not lunge forward or bend at the waist, as this causes the canoe to porpoise up and down inefficiently.

Switching sides

Keeping the canoe going straight is a matter of calling switches at the right time. The canoe tends to gradually track away from the side the stern paddler is paddling on. The remedy is to switch sides every eight to 12 strokes. Solo paddlers may have to switch sides more often.

After the call to switch, finish your current stroke, then bring the shaft hand upwards, while releasing the paddle’s grip end with your top hand and swinging the paddle over the canoe to the new side. By the time the paddle is passing the centerline of the canoe your hands should be in their new positions so you can start your next stroke without breaking rhythm. The switch will take some practice to do with finesse at speed.

Peter Heed is co-author of marathon paddling bible, Canoe Racing: The Competitor’s Guide to Marathon and Downriver Canoe Racing, and a many time national marathon race champion. He’s currently the president of the United States Canoe Association.

A canoeist practices the sit-and-switch paddling technique from the middle of a solo canoe. | Feature photo: Pål Krogvold

This article was first published in the Spring 2016 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2016 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.