“It’s a five-eagle day,” exclaimed rafting guide Katie Duffie as we glided into a calm eddy to admire a young bald eagle perched above our heads. It was summer 2023, and we were catching our breath on a remote stretch of the Upper Klamath River in Oregon. As the bald eagle winged its way overhead and upriver in search of lunch, I couldn’t help but think its hunting was about to get a whole lot better. It was a fleeting thought as Duffie prepared us for the next rapid.

Dragon was one of six named class IV rapids with a steep drop followed by two jagged submerged rocks—dragon’s teeth—and a set of drenching waves at the end. It was on a heart-pounding five-mile section of the Upper Klamath, known as Hells Corner, part of a longer 13-mile stretch of exhilarating big water. Even in drought years, when other rivers were too low to raft, the Upper Klamath had a reputation as one of the best summer whitewater rivers in the West. Its flow depended on a combination of geography—a steep, narrow canyon constricting the river—and hydrology, a water flow of 1,000-3,000 cubic feet per second. Its flows wouldn’t have existed without an assist from a hydropower dam just upriver, the John C. Boyle. And they don’t exist now.

My day trip was one of the last guided rafting trips on the Upper Klamath, taken on the cusp of its historic transformation. Construction has begun to demolish four aging dams on the Klamath, including the John C. Boyle. It’s the world’s largest dam removal project and aims to return historic salmon runs to the Klamath—once the second-largest in the lower 48 states—and free 400 river miles on one of the most culturally important rivers in the western United States. The implications for river enthusiasts will ripple for years to come.

Last call on the Klamath River

What’s the dam problem?

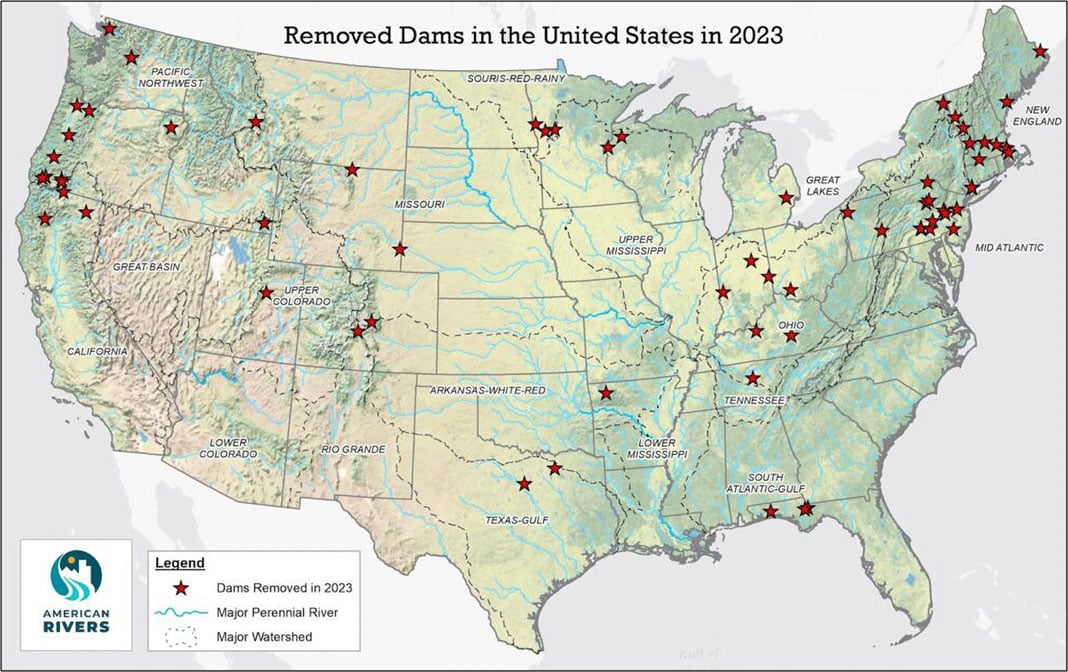

The Klamath’s restoration is part of a national reevaluation of dams on America’s rivers. According to river conservation nonprofit American Whitewater, there are 50,813 miles of whitewater rivers in the U.S. If you superimpose a map of major rivers with the locations of the 92,075 dams inventoried by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, you’ll discover only a handful of rivers flow freely—California’s Smith River, Montana’s Yellowstone, Idaho’s Salmon and Alaska’s Yukon all flow hundreds to thousands of miles undammed. The actual number of river-blocking dams in the U.S. far exceeds the official inventory, according to American Rivers, since the Army Corps inventory only includes dams higher than 25 feet or ones posing significant flood risk downstream.

“What makes a river attractive for whitewater boaters, a high gradient with lots of flow, also makes a good site for a hydropower dam,” says Dr. Thomas O’Keefe, a river ecologist and Pacific Northwest Stewardship Director for American Whitewater. Where dams and whitewater boating opportunities overlap, American Whitewater advocates for protecting navigable rapids and the interests and safety of those who enjoy running them.

While controlled water releases at some dams benefit outfitters and boaters by providing reliable flows, the ecological toll is undeniable. Dams block fish migration, alter natural river flows, and can significantly degrade water quality through impoundment and pollution concentration.

The Copco Reservoir on the Klamath was frequently overrun in summer by a bright-green toxic algae bloom, which can cause liver damage and poses risks for fish, wildlife and communities downriver, including the Hoopa and Yurok tribes. Poor water quality from the Copco Reservoir contributed to a massive fish kill in 2002, prompting renewed calls to undam the Klamath. It took another 20 years of advocacy to reach an agreement with the dam owners and transfer ownership to the non-profit Klamath River Renewal Corporation, beginning the process of removing the dams and restoring the river.

Certainly, dams have their utility. They provide flood control and hydropower electricity, and the reservoirs they impound can store water for farmers and cities, and create recreational opportunities and barge transportation. For those reasons, the U.S. was on a tear to build dams in the last century, at the rate of four a day from 1930 to 1970. But if the 20th century was the era of dam building, the 21st century is looking to be the era of selective unbuilding.

Many of these older dams, which have a design life of 50 to 100 years, are becoming unsafe and at risk of failure, overrun by silt and crumbling concrete structures. Dam operators have also run afoul of the Endangered Species Act, which requires building fish passages or replenishing stocks to prevent severe decline or extinction of endangered salmon and other species. In many cases, the profits from hydroelectric generation, which can be replaced by renewable wind and solar, aren’t enough to offset the costs for repair and for protecting fish, leading to the designation of a deadbeat dam.

Restoration’s ripple effects

Dam removal, deadbeat or otherwise, can’t come soon enough for the Indigenous communities whose identities and ways of life are deeply intertwined with impacted rivers. A study published in Environmental Research Letters in 2023 estimated more than a million acres of tribal land in the U.S. have been flooded by dams, adding to centuries of land seizures and forced displacement.

New coalitions between tribes, government, scientists, outfitters, nonprofits, whitewater enthusiasts, anglers and farmers are finding opportunities to remove dams that have outlived their usefulness and to restore rivers and fisheries. In 1999, the federal government determined for the first time the benefits of a hydroelectric dam were outweighed by the harm it caused to aquatic habitats and fisheries, leading to the removal of Edwards Dam on Maine’s Kennebec River.

For big hydro dams, unbuilding is not an easy or quick process. Removing two dams on the Elwha River in 2011, the largest dam removal project in the country at the time, required an act of Congress and took three years to complete. For over a century, these dams blocked salmon from accessing 90 percent of the watershed and caused a population crash. The subsequent restoration led to a resurgence in Chinook salmon numbers, allowing the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe to resume limited fishing in 2019. Boaters also returned to explore the restored Elwha Canyon, once blocked by a dam, through a class IV section paddlers cheekily call That Dam Rapid.

Another success for boaters was the tear-down of Condit Dam on Washington’s White Salmon River. On October 26, 2011, a hole was blasted through the bottom of the 125-foot-tall dam, releasing an enormous plume of charcoal-gray water down the river and draining the reservoir in hours. A year after removal, kayakers and rafters were running class III to class V rapids on the White Salmon, past the nearly invisible former dam site and extending the paddle for an additional five miles through the former reservoir to the Columbia River. Salmon and steelhead also found their way back to historic spawning grounds above the former dam, though not in full force as they still have to negotiate the gigantic Bonneville dam downstream.

Whether the Klamath dam removals will be as successful remains to be seen, but work has ratcheted up. The first of the four dams, Copco 2, was torn down in fall 2023, opening a section of river called Ward’s Canyon, which had been dewatered since 1925. In January 2024, tunnels were opened at the bottom of the three remaining dams to drain the reservoirs behind them. Construction crews will work simultaneously beginning in March, dynamiting and tearing down the structures with heavy equipment and hauling away debris.

The Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) expects the dams on the Klamath will be gone by year’s end. During reservoir drawdown, mudflats emerged from the former footprint. Restoration crews, including members of the Yurok tribe, will plant millions of native seeds to restore and stabilize soils along the riverbank. Crews will also connect tributaries and restore salmon spawning grounds to create more habitat on the free-flowing river. The removal of four dams in such a short timeframe is a feat of planning and engineering and is considered the best way to clear the river of reservoir sediment quickly, as too much turbidity depletes oxygen and harms fish.

The paradox of reliable whitewater

Dam removal can be a paradoxical topic for boaters and outfitters who care about both river health and reliable whitewater. While removing the John C. Boyle dam marks a significant win for river restoration, it also ushers in a new era for whitewater rafting on the Klamath, necessitating adjustments from both outfitters and enthusiasts.

Water releases from the John C. Boyle had been a mainstay for a handful of southern Oregon rafting companies for four decades. Despite the hit to business, “We strongly believe dam removal will lead to a healthier Klamath River system and, if done correctly, would also be good for surrounding communities and local economies,” the Upper Klamath Outfitters Association stated.

But transformation isn’t without growing pains.

“It hurts,” said Bart Baldwin, owner of Noah’s River Adventures, which has run trips on the Upper Klamath since the 1980s. The Hells Corner trip made up between 40 and 60 percent of business. “It’s one of—if not the best—whitewater trip west of the Rockies. You have warmer water, beautiful scenery, and mile after mile of rapids.”

In 2023, Noah’s and other Upper Klamath River outfitters offered big water summer trips for the last time, serving an estimated 4,000 clients and generating more than $500,000.

“It’s bittersweet, like saying goodbye to an old friend,” added raft guide Duffie, who guided my trip last year through Hells Corner below the John C. Boyle dam. “I’m sad to lose big exhilarating whitewater all summer. But I’ll be happy to see the river free and wild again and excited to see what new stretches of whitewater open up.”

Before work began, KRRC commissioned a group of hydrologists and whitewater boaters to evaluate potential changes to river flow and impacts on boating after dam removal. While acknowledging summer flows will be lower through Hells Canyon and require higher technical skill to navigate, the newly opened Ward’s Canyon will provide “exciting new whitewater boating opportunities,” according to the commissioned report.

Thanks partly to American Whitewater advocacy and commercial outfitter requests, the restored Klamath River should offer easier access with more put-in and take-out locations. Previously, more than 90 percent of boating was commercial due to the difficult logistics and rapids. The trickiest part for outfitters in the future will be timing.

“Flows will be more variable,” said Duffie. “It will be weather dependent, and we’ll watch snowfall and rain closely.” The best whitewater opportunities in Hells Corner will shift to spring, between March and May, rather than summer and fall, when dam releases artificially boosted the flow from less than 1,000 cfs to 1,500-2,000 cfs.

Noah’s River Adventures owner Baldwin is considering how to pivot his business once the river opens again in 2025. “I have to be open-minded; our guests have to be open-minded,” he said. Baldwin will run spring trips but said it will be a different experience with wetsuits rather than shorts and sandals. “It might be sleeting at the put-in. They’re still going to have a good time and remember the experience for a long time, but on a 100-degree day, they’re not worried about water splashes because it feels so good,” he added.

Baldwin might offer fishing trips or multiday floats through parts of the river previously off-limits or flooded by reservoirs. He’s testing smaller, lighter boats to get through rapids with lower flows. The readjustment the Upper Klamath River outfitters face is unique but also increasingly common as more dams are dismantled and rivers freed. Eighty dams were removed in the U.S. in 2023, according to America Rivers. The organization predicts another 90 to 100 will be removed this year, with the number of dam removals growing at 10 percent per year.

Now that removal is underway, Baldwin looks forward to seeing how the river sorts itself out. “I’ve always thought, ‘This sucks this has been taken away from us,’” he said. “But I’ve been down to see the river flowing again with no artificial peaking; it affected me more than I thought it would.”

First call on the Klamath

Everyone will have to wait until 2025 to boat the undammed Klamath, but the rights for first descent belong to a special group of Tribal youth organized by Rios to Rivers. For two years, Indigenous youth from the Yurok, Hoopa, Karuk and other local tribes have been learning whitewater kayaking skills in preparation for a 400-mile journey from source to the sea. Whitewater is a new experience for some intertribal youth; others have a deeper relationship with rivers.

“I grew up on the Trinity and Klamath rivers, knowing those are our home places and our sacred places, where all of our food came from and a lot of who we are in our culture,” said Danielle Frank, a Hoopa tribal member and the developmental coordinator for Rios to Rivers’ Paddle Tribal Water program. She was born right after the 2002 fish kill on the Klamath and was submersed in the climate movement from a young age. Her father was a frontline activist who fought to remove the Klamath dams.

“We’ve been hearing about this for a long time, and it’s finally here,” she said. “It’s a pretty momentous occasion, and celebrating it with these kids is pretty special.” Frank is currently studying environmental science and hopes to become a fisheries biologist so she can continue spending time on the water.

While learning to whitewater kayak is essential to Rios to Rivers, the training program is more than a recreational pursuit. It’s also about healing and reconnecting to a culture that once navigated these waters in canoes.

“Technically, this is not a first descent,” Frank said. “Our people have been in this river on canoes since time immemorial.”

Frank and the other Rios to Rivers leaders are planning the weeks-long trip next summer with 28 Indigenous youth, primarily from the Klamath River basin. In the process, they traveled to the deconstruction sites and learned how the river and its salmon populations will be restored. They’ve met with elders and members of the Shasta tribe to discuss the tribe’s sacred connection to Ward’s Canyon. Part of being responsible for the first descent, she points out, will be modeling ways to show respect and honor the river’s sacred places. Along the way, she wants participants to develop their leadership skills and reflect on how the river and their futures are intertwined.

“I hope we can teach these kids there’s a reason to stay home and build a life around the river. With a restored river, I hope it’s another avenue for them, rather than leaving the reservation.”

Mary K. Miller is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. A grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists supported her reporting on this story.

Watch the trailers:

Rafters on the Hells Canyon section of the Upper Klamath River. | Feature photo: Noah’s River Adventures

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.

Found a major error in this article… although I know this is more about the Klamath river dams, there is one paragraph regarding the Condit Dam removal in 2011 in Washington State. At the end of the paragraph it is mentioned about the salmon runs and that they “still have to negotiate the gigantic Grand Coulee Dam three miles downriver”. Please check your geography. The Grand Coulee Dam is nowhere near the White Salmon River. It is hundreds of miles upriver. The closest dam is 30 miles downriver (not 3) from where the White Salmon enters the Columbia and it is Bonneville Dam.

Doris, thank you for this correction. The article has been updated to address the error.

Interesting article which leaves out any data to support the statement; “In many cases, the profits from hydroelectric generation, which can be replaced by renewable wind and solar, aren’t enough to offset the costs for repair and for protecting fish, leading to the designation of a deadbeat dam.” Such as where is the ROI, return on investment, to determine what the capital costs are to purchase and maintain enough wind and solar power equipment to replace the electrical generation from the dam? As well as the life cycle costs for wind and solar power equipment vs the maintenance costs a 50-100 year dam.

So I suspect the electrical short fall will need to be made up by; natural gas, nuclear or coal. If not then users will face brown outs like the

southern neighbor and not be able to charge all the elecrical vehicle.