Regardless of where you’re from, you’ve probably heard of India’s Ganges River: It is one of the world’s longest rivers at nearly 2,700 kilometers. Tracing the border of India and Bangladesh, the Ganges basin is home to more than half of India’s population, and it’s considered holy to people of Hindu, Buddhist and Jainism faiths.

Source to sea on the lifeline of India

Expedition paddler and raft guide Rency Thomas grew up knowing that the Ganges River is central to his Indian culture and national identity.

“In India, rivers are considered very sacred and holy,” says the 36-year-old resident of Manali, part of the state of Himachal Pradesh, in India’s Himalayas. “The River Ganga is the most sacred river of all. It is believed that by bathing in the holy waters of Ganga one can purify the soul from all sins and attain salvation.”

The Ganges has another important meaning to Thomas: It’s where he discovered paddling.

“Born and raised in India, the River Ganga was part of our lives in stories, in scriptures, in academics like geography and history,” he says. “Somehow, the river has always fascinated me.”

An exploration of the Ganges

A self-propelled source to sea expedition was the ultimate way for Thomas to pay tribute to this sacred waterway and satisfy his own desires to know it more intimately. He knew portions of the Ganges were remote with difficult access, and the river is also impeded by six dams. Thomas also faced the challenge of dealing with his own chronic arthritis, which makes it difficult for him to sit in place for long periods of time.

“I have been a chronic arthritis patient since the age of 20,” he says. “Many of my joints are affected and have limited mobility. Last year I had a very severe flare-up and was bedridden for almost two months. Two of my fingers on my right hand were deformed with limited mobility. This scared me and made me want to finish my dream project as soon as possible.”

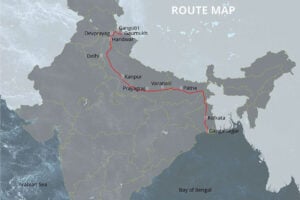

To convince himself that his body was up to the task, he spent a month putting in eight-hour days in his kayak, discovering his personal limits on the water. Last fall, feeling prepared, Thomas set out on foot on the Gaumukh Glacier at 4,023 meters of elevation in the Himalayas, the source of the Bhagirathi River which in turn feeds the Ganges. After 23 kilometers of trekking, Thomas paddled 60 kilometers in a whitewater kayak on the Bhagirathi, and then switched to a sea kayak on the Ganges River itself. Along the way, he also put in about 800 kilometers of mountain biking to avoid obstructions or other difficulties on the river.

“It was pretty much a pure exploration in the river as there are no navigation charts or earlier data,” Thomas says. “The river changes its course every year. Even the satellite imagery is not reliable as it’s been recorded before monsoon.”

Tracing the lifeline of India

The Ganges River is home to incredible wildlife and Thomas encountered millions of migrating birds, elephants, golden mahseer (an endangered species of carp), freshwater turtles and gharials (a critically endangered, fish-eating crocodile). The greatest highlight for Thomas was seeing Gangetic dolphins, a unique freshwater dolphin that’s elusive and difficult to observe, swimming alongside his kayak.

The characteristics of the Ganges changed considerably over the course of Thomas’ 95-day expedition from the Himalayas to the Bengal Sea. The waterway passes through five different Indian states, and Thomas notes that for just about every 100 kilometers of river there’s a distinct culture and dialect. Just as Thomas sought to explore the river as a means of challenging his body and getting to know his home country, he discovered the Ganges River is truly “a lifeline for the people” of India.

“The culture and life around this huge river is so overwhelming.”

Gratitude for the River Ganga

As he neared the end of his 2,600-kilometer sojourn, Thomas was left with a firm feeling of resolve that’s gaining momentum across India as local environmentalists battle to leverage legal “personhood” status to protect the Ganges River.

“The river needs to be safeguarded,” Thomas asserts. “Any destruction to this river in terms of pollution and building dams can be very devastating to the rich wildlife and people. The people living around this river are dependent on it for drinking water, fishing, irrigation—even the industries around rely on the water from Ganga. Any developments in and around Ganga must be sustainable and special focus and awareness should be given in keeping the river clean.”

Completing his journey felt like “a dream come true.”

“I find solace in outdoor sports,” Thomas says. “I love high-altitude trekking and mountaineering, but it’s on the water where I feel most at home. I feel so proud of my accomplishments but at the same time, so humble and thankful to River Ganga for keeping me safe.”

Feature photo: Ponni M. Nath