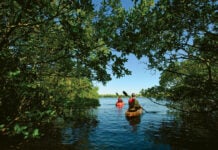

As paddlers, we are particularly moved by wild, coastal landscapes. One such special place exists on Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore. Those in the know appreciate its surf-washed beaches, rugged cliffs, moss-cloaked forests and raw, natural beauty.

It’s called the 100 Wild Islands.

In the nearly 20 years I have paddled this area, which actually includes 282 islands and islets sprawling across 27 square kilometres—some 250 kilometres of shoreline stretching along 30 kilometres of mainland coast between Clam Harbour and Mushaboom, I’ve rarely seen other people on the water. Far more regular sightings are of eagles and ospreys wheeling overhead or tending young in their nests. Porpoises, seals, schools of fish, and deer are more commonly seen than other visitors.

“It’s true wilderness on an amazing scale, a completely wild archipelago of islands and most of the habitat has been completely undisturbed since the last ice age,” says Bonnie Sutherland, executive director of the Nova Scotia Nature Trust. “These islands show us what nature is like if humans don’t interfere in any way, and that kind of land is shrinking in this world.”

Even more incredible is that this massive wilderness archipelago lies so close to a major urban centre—the provincial capital of Halifax is just an hour’s drive southwest along the coast. Inevitably, the islands caught the eye of developers.

Plans were drawn up for an exclusive golf resort and seaside mansions on 533-acre Borgles Island, smack in the middle of an interconnected and globally significant mosaic of coastal bogs, barrens, saltmarsh and freshwater wetlands—and one of the most beautiful double crescent, white sand beaches I have ever had the luxury of camping on.

The Nova Scotia Nature Trust

Currently, less than 5 per cent of Nova Scotia’s coast is protected. Over 85 per cent is privately owned and faces unprecedented pressures, threatening the integrity of coastal habitat and biodiversity, as well as public access and enjoyment. The 100 Wild Islands represent one of the last and best opportunities in North America, perhaps the world, to protect such a vast, untouched, ecologically rich and diverse coastal archipelago.

The islands’ significance has been recognized twice before. In the early 1970s, the federal government made moves to appropriate the privately owned islands—comprising some 40 per cent of the archipelago—to create a national park, but locals and landowners fought back the attempt to seize their land.

The provincial government then looked at making a park in the area, but again the bid met with roadblocks. Ultimately, the province set aside only two small parks at Taylor Head and Clam Harbour Beach.

The stalemate between private owners, the Crown (which lays claim to 4,000 acres of the 7,000 acres of islands) and would-be conservationists turned on the interests of one man.

Paul Gauthier grew up on the Eastern Shore in Cole Harbour before moving to California to pursue a career in Silicon Valley. Now in his forties and a successful entrepreneur, he’s an avid adventurer who has traveled the world scaling some of its highest mountains and escaping into wild places on the water.

A decade ago, while looking at charts of the Eastern Shore, Gauthier noticed the massive, unprotected wilderness area in the backyard of his hometown. It compelled him to act. In 2007, he approached the Nature Trust with the vision of protecting the entire archipelago, and the dream of the 100 Wild Islands was born.

The Nova Scotia Nature Trust first started protecting private properties in the area in 1997. The Trust’s unique land trust approach works with each landowner to arrange land donations, negotiate purchases or forge conservation easements. By working to ensure locals and the general public continue to have access to recreate in the area, the Trust has won over residents and local businesses. By 2007, they had protected Ship Rock and Shelter Cove conservation lands, paddlers’ paradises that are home to beautiful beaches, dramatic cliffs and some of the oldest rocks on earth.

Still, it was Gauthier who gave the project the momentum it needed when he stepped up to match every dollar donated to the 100 Wild Islands campaign, which launched in 2011, eventually contributing half of the $7 million goal set by the Trust. For its part, the province agreed to designate all government-owned land within the archipelago as part of the Parks and Protected Areas Plan.

“It was big and ambitious,” admits Gauthier. “But taking this beautiful place and keeping it pristine and protected resonated with me. These islands will stay this way forever. They won’t get turned into golf resorts or cottage subdivisions.”

Long neglected islands

The scientific community knew little about the area and its offshore island ecology before Gauthier funded three summers of exploratory field studies. Research by Nature Trust scientists and ecologists revealed the 100 Wild Islands contain every type of coastal habitat found in Nova Scotia: wetlands, headlands, beaches, saltmarshes, sheltered coves, sea cliffs, eelgrass meadows, lagoons and even rare island lakes. Much of it is an intact, bio-diverse ecosystem that exists largely as it did 10,000 years ago.

The potential scientific findings on these long neglected islands is staggering. Perhaps most surprising was the discovery of some of the East Coast’s only known temperate rainforest. The 100 Wild Islands are characterized by old-process forests. A shorter growing season with harsh winter storms off the North Atlantic does not allow for large, ancient trees like those found in milder West Coast rainforests, but the undisturbed windfall creates a unique and evolving habitat.

The area also provides refuge for more than 100 species of birds. It shelters and supports diverse seabirds, including imperiled species such as eiders and harlequin ducks. Shorebirds can often be seen cruising beaches for food. Various songbirds can be heard as you quietly ply the waters. You may catch the melodic whistling of a rare fox sparrow, boreal chickadee or a black warbler whose numbers are dwindling on the mainland.

On Borgles Island, researchers have found that near-pristine forest and coastal habitats support “globally significant ecology and biodiversity,” making it an integral piece of this benchmark ecosystem. Fortunately, Borgles is now protected, saved from the clutches of condos and 18-hole courses. But Borgles is just one island in this very special archipelago. As this story goes to press, more than 70 per cent of the 100 Wild Islands have been protected.

A success story

To witness local enthusiasm and support for the 100 Wild Islands campaign, a paddler should stay at Murphy’s Camping on the Ocean. The campground is in Murphy’s Cove, and owned by Brian Murphy. He has a strong appreciation for why visitors are drawn to the area, and why it’s been important to generations of Murphys.

“These are truly gorgeous islands,” Murphy gushed to a reporter for The Chronicle Herald. “When you fly over them, it looks like Bermuda—white sand, lots of marshes and seabirds—this has to always stay the way it has always been.”

If you’re already familiar with the paddling potential of these crystal clear waters, you probably owe Dr. Scott Cunningham and Gayle Wilson a debt of gratitude. The couple started Coastal Adventures 35 years ago in Tangier, located in the heart of the 100 Wild Islands. They have been sharing their beloved waters with kayakers ever since.

Cunningham says the archipelago cast its spell the very first time he glided his kayak among its exposed headlands, idyllic coves and incredible beaches. He literally put the area on paddlers’ maps when he included the 100 Wild Islands in his guidebook, Sea Kayaking in Nova Scotia, first published in 2000. He writes:

“It is the island archipelago that distinguishes the Eastern Shore and makes the region such a pleasure for the paddler. Nowhere else in the province will you find the number and variety of shoals, islets and islands as along this neglected coast…You will be sharing them with only the seals and sea birds.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that the 100 Wild Islands rival many world-class kayaking destinations. The archipelago boasts a terrestrial wilderness twice the size of British Columbia’s Broken Group. It’s more intact than Washington’s San Juan Islands, Maine’s Casco Bay islands or the St. Lawrence River’s Thousand Islands National Park.

It’s also fair to say that the 100 Wild Islands represent one of North America’s most significant coastal conservation success stories in recent years.

“We’ve grown so used to seeing places that we call wild, but they are not really wild,” says well-known environmentalist, Yvon Chouinard. The owner of Patagonia outdoor clothing company became a major donor to the campaign after a recent visit to the 100 Wild Islands.

“I’ve been involved in conservation all across the planet, and these islands are truly unique, like no other place I’ve ever been,” Chouinard says. “That this archipelago could be so pristine, so close to a city, yet untouched—it just makes so much sense to protect it.”

Paddle the 100 Wild Islands

When: Most precipitation falls in winter and spring, with a fair amount arriving as fog. Rain and storm days are possible any month in Nova Scotia, but the finest paddling weather usually occurs from July to late September.

Where: Both Coastal Adventures and Murphy’s Cove offer good water access for kayakers. Additional public access can be found at Clam Harbour Provincial Park and Taylor Head Provincial Park, which conveniently lie at the west and east end of the 100 Wild Islands, respectively. Both are wonderful protected areas in their own right. The Nature Trust also plans to add visitor friendly facilities and water access from the mainland highway.

Stay: Pitch your tent at Murphy’s Camping on the Ocean before heading out. Great campsites can be found throughout the 100 Wild Islands, with Borgles Island, Shelter Cove and Wolfes Island offering some of the best.

Outfitter: Coastal Adventures in Tangier, Nova Scotia, offer three and five-day guided tours of the 100 Wild Islands throughout July and August 2016.

How To Help: The 100 Wild Islands Legacy Campaign is less than $300,000 from reaching its goal of $7 million. Learn more and help save this unique coastal legacy at 100wildislands.ca.

Gregor Wilson volunteers with the Nova Scotia Nature Trust and spent three seasons guiding kayaking on the Eastern Shore. He spends much of his free time skiing, paddling, hiking and trail building.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.