Of all the epic portaging fails that have happened in a lifetime of canoe tripping, none was more memorable than a tumble on the bouldery high ground in the headwaters of the Lockhart River system northeast of Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories a few years back. We were in the early days of a seven-week canoe trip north toward Bathurst Inlet with no resupply, so there was a welter of stuff to carry when we ran out of paddleable water.

Tumplines: How to make portaging great again

I’d carried the canoe and a blanket pack first, followed by another epic load of food. Then, saving the best to last, I hefted up our kitchen wanigan—aka “that f@#$%^& box.” I got the tump settled on my brains, heaved a Pelican case containing 33 pounds of camera gear on top of the wanigan, and staggered off to what could have been a life-altering crash.

It happened at the end of the portage, as many faux pas do. On my first trip, I tiptoed across a field scatter of boulders with the canoe and flipped it down where it sat nicely and could be reloaded with gear. On this trip with the wanigan, thinking the carry was all but over, I momentarily lost concentration on those last few steps. In a heartbeat, a slip on the rock pitched everything forward. The Pelican case arced ahead and splashed into the water, as did the wanigan, leaving me to continue the fall and do a very inelegant faceplant into the rocks.

But here’s the lucky thing: pack straps would have kept the load more or less on my back and propelled me face-first into the rocks with even more force. Because the load was attached to me with just a wide leather tump strap, the load and I parted company for the betterment of all concerned. There was damage to me and the wanigan, but it could have been much worse. Saved by the tump, as it were. In honor of being delivered from death by that unassuming bit of kit, I’d like to send a little love in its general direction.

When it comes to load carriage, we’re awash in dubious improvements to what was very likely the first and simplest way to move stuff from one place to another: the tumpline. Back straps, external frames, internal frames, Trapper Nelsons, widgets, zippers, waist belts and chest straps—all came along after the tumpline and eclipsed the single head strap for reasons that might include the invention of cameras and other reasons to use your hands while carrying a load.

But, if you follow back load carriage to its first principles, the tump strap was the first and possibly the best innovation for getting loads from one place to another with the least possible effort.

My affection for tumps is in some measure due to the innovative genius of French-Canadian shoemaker Camille Poirier, who transmuted the voyageur tradition of carrying heavy loads with one strap around your head to the green canvas, leather backstrap Duluth Packs created in the 19th century. The Woods Outdoor Company knocked these packs off in Canada, creating a family of packs purchased widely by Canadian summer camps, where I first began my canoe-tripping career.

We took these packs on canoe and hiking trips. On these journeys, I came to appreciate carrying at least some of the load on your head made a world of difference in the distances you could cover without collapsing into a weepy heap of protoplasm with no place to turn for respite.

It wasn’t until I began canoe tripping with friends that the idea of carrying a load with only a tump strap dawned. Tripping camps had been using wanigans with tumps for years. Once we got the kitchen wanigan going, it seemed the best way. For starters, it kept the spine straight and, once you got used to it, appeared to be a way to carry a heavier load for a longer distance than anyone ever could with just shoulder straps. The tump also allowed you to breathe because no straps constricted your chest. Maybe the Nepalese porters, African water carriers, beleaguered voyageurs and all those early hominids who needed to carry a load from place to place had something going on.

The incontrovertible proof that anyone serious about carrying a load should ditch the shoulder straps and fancy accoutrements of frames and instead adopt the tump strap comes from the 11th Canadian Brigade Tumpline Company during World War I. The problem was getting supplies from roads to the trenches in France, which often involved travel over muddy, conflicted ground not navigable by horse and cart. The only solution was to hand-bomb everything, which took an inordinate amount of manpower. Thanks to the wisdom of Staff Captain F.R. Phelan, a member of the Canadian Expeditionary Force who had done “considerable hunting and fishing in the back woods of Quebec,” the tumpline was introduced to the Allied war effort.

Phelan showed switching from backpacks and conventional hand-carrying of ammunition and supplies to tumplines reduced the manpower needed to supply the trenches by at least 50 percent. For example, a 93-pound Vickers machine gun could be carried by just one man with a tump. It would have otherwise required two men to carry it into the field. So chronicles an article by F.R. Phelan published in the Canadian Defence Quarterly in October 1928.

Twelve picks for digging trenches would require three men with ordinary carriage, but with a tump and a few carefully tied knots with the tump ties, the 78-pound load could be easily carried by just one soldier. The same is true with a load of six sheets of corrugated iron. Both cases would result in a 66.6 percent saving in labor and personnel.

Who knows if the tumps saved lives by moving the loads forward when members of the Tumpline Company slipped and pitched into the muck, but I’m guessing they did.

James Raffan is the former executive director of the Canadian Canoe Museum. He’s also an author, explorer and occasional Zodiac driver. Tumblehome celebrates the rich heritage of canoe culture.

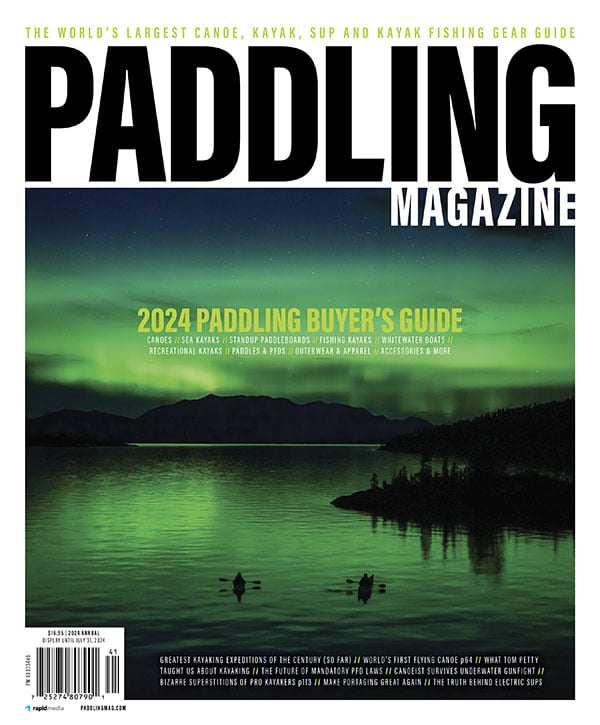

Tumplines are worn on the head, usually perched just behind the hairline—not over the forehead. Leaning forward aligns the load with the spine, utilizing the back for support. | Feature photo: David Jackson

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Paddling Magazine.