There are many ways of improving kayaking performance. The obvious one most paddlers go to first is simply paddling more. Unfortunately, or fortunately depending on how you look at it, the gains from this alone are limited and you quickly run out of time unless you are a professional athlete. One mode of training that most paddlers neglect or struggle to do well is strength training in the gym or at home. Smart strength training can have a huge impact on kayaking performance.

Whether you are a competitive paddler training for your next race, looking for adventure in whitewater or love the freedom of touring, you can improve your paddling experience with strength training. A well-planned kayak strength training program will help you paddle faster and longer, protect you from injury, allow you to get more out of yourself or just enjoy the journey more by not being as fatigued by the demands of paddling.

In this article, I’ll go over the fundamentals of strength training for kayaking so you can get started in designing a program that works for your goals and lifestyle.

[This article is part of The Ultimate Fitness Guide For Paddlers. Find all the resources you need to stay healthy and fit for paddling.]

How strength training improves your paddling

Strength training both directly and indirectly improves your performance in the kayak. Let’s go over how this works.

Direct improvements: helping your muscles generate more force while kayaking

Direct improvements to your paddling come from an increase in the muscles’ ability to generate more force. This force production comes as a result of increases in muscle fibre size and neural activation. Force production—or how hard you pull on the paddle—is a key component of the power production equation, Power=f*v, where f is force and v is velocity or how fast you pull your paddle (aka stroke rate). By increasing either of these factors you can increase power and therefore your boat speed.

While you are not always paddling at your max power, having greater power production capacity also means you can power your boat up faster to catch that wave, make that eddy or get yourself out of a sticky situation.

Indirect improvements: providing you with greater resiliency to injury while kayaking

On the other hand, indirect improvements in the kayak from strength training come from improved core control, joint stability, and ligament and tendon strength, all of which make a paddler more resilient to injury. When a paddler has higher injury resilience they are able to train harder on the water and manage a higher training load which will result in increased performance. As a side note, improved core control can also have a direct impact on performance through improved transfer of power and maintaining good paddling technique longer as you start to fatigue.

While it is not black and white in terms of when you get direct and indirect performance improvements, generally indirect performance gains come in the early phases of training and you will be able to build your direct performance gains off this sounds platform in the future. The type of training required to obtain the direct performance gains is more advanced and demanding than the training required to obtain the indirect improvements. Regardless of ability, all paddlers can and should be doing some low-level strength work to get these indirect performance gains.

Focus points for paddling strength training

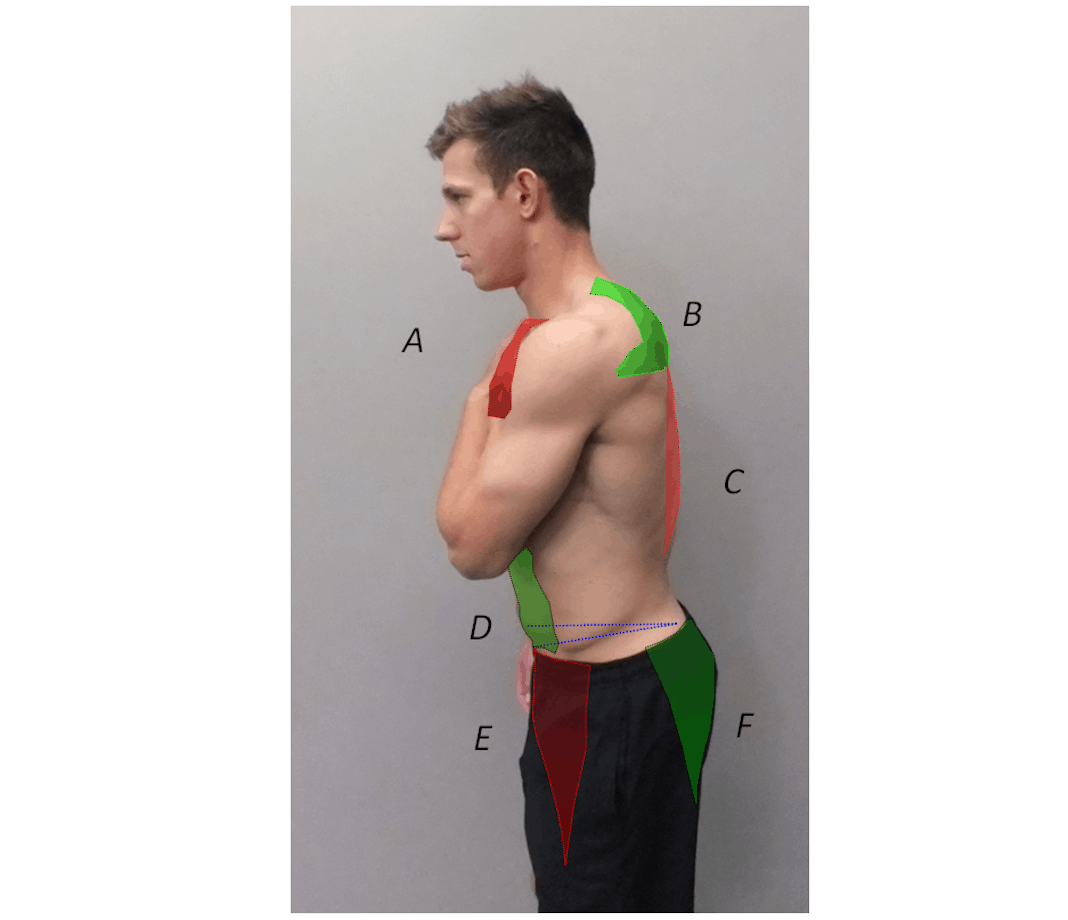

The nature of paddle sports and the modern lifestyle leaves many paddlers with some really tight and strong muscle groups (outlined in red above) and others that become weak and stretched (outlined in green). While there are hundreds of different exercises and plans you could do in the gym, for 95% of paddlers the best place they can put their attention initially is on strengthening these green areas while stretching and mobilizing the red areas. If you can do this then you will be taking a large step in the right direction.

[ Read also: 7 Of The Best Cross-Training Activities For Paddlers]

Pectoral muscles

The pectoral muscles become extremely tight with training and life in general. Accordingly, paddlers should focus special attention on this area with their stretching and mobilization

Because the strong pectoral muscle group is pulling the shoulders forward, the muscles of the upper back are under constant tension. This prolonged tension causes the muscles to atrophy (decrease in size) and “creep” (lengthening of the muscle fibre). This then leads to the muscles becoming weak and inactive. With this in mind your focus needs to be on performing pulling exercises such as the bent-over row, bench pull, and cable or seated rows to strengthen this area.

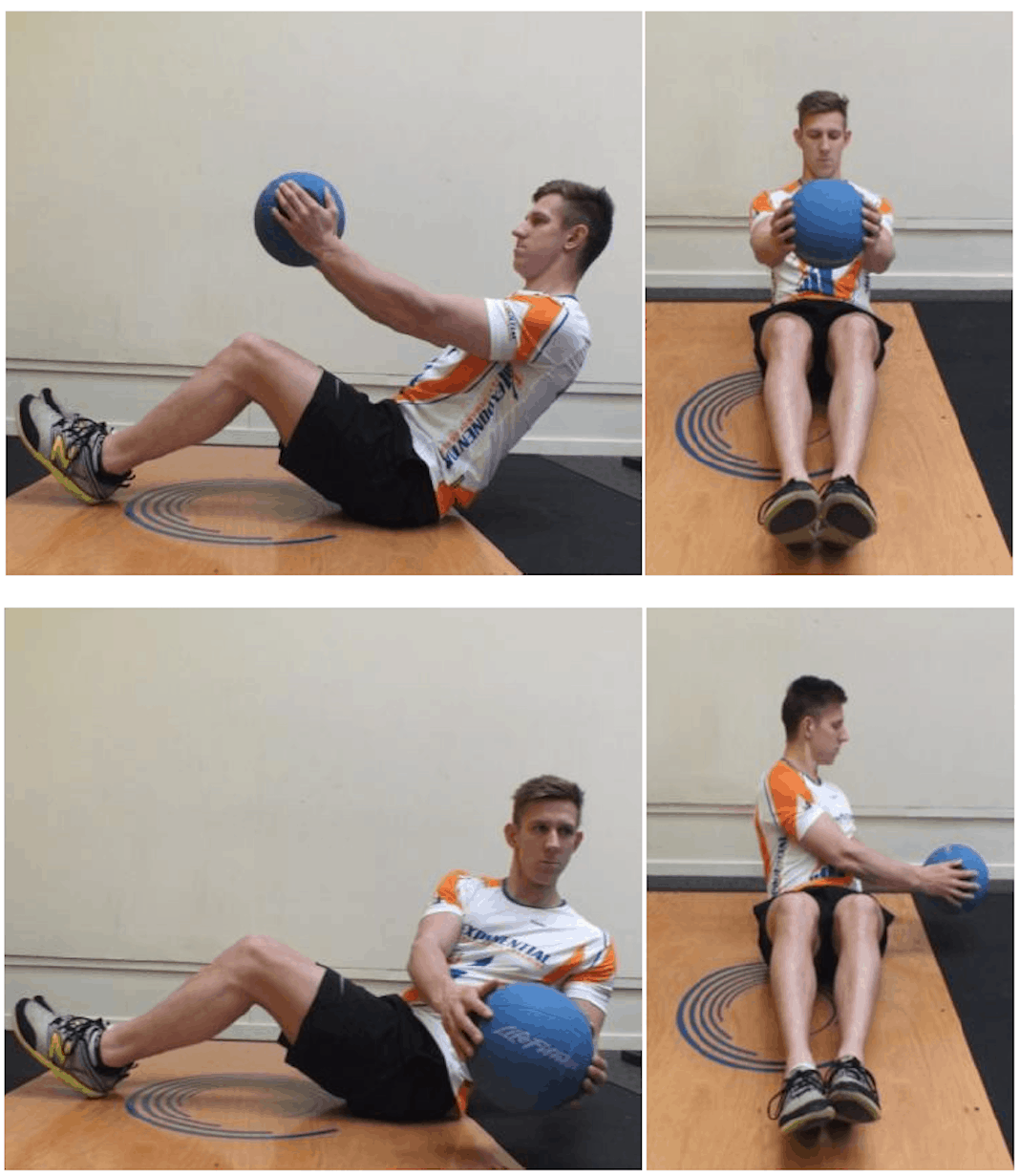

Core muscles

Due to the kyphotic rounding of the shoulders, forward head posture and inactivity of many of the key core stabilizers, the erector muscles of the spine have to work overtime to keep it stable. This can lead to lower back pain and restricted movement, particularly rotation. Your strength training should focus on developing the surrounding core musculature to take some of this load off.

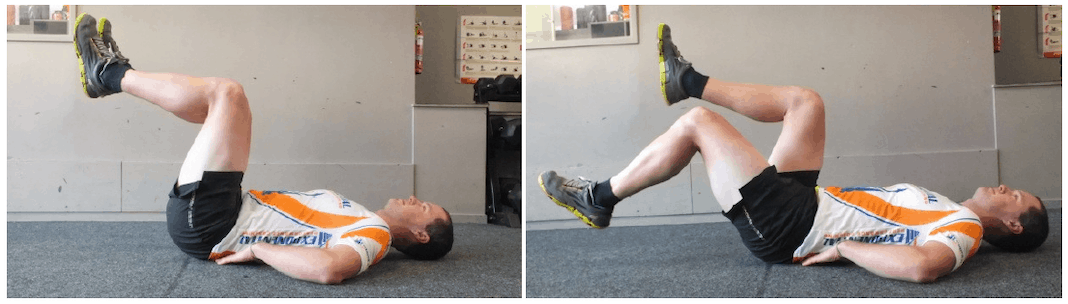

The core is the key link between the upper and lower body. For paddlers, it is critical for the transfer of power and stability. While the rectus abdominis (“six pack”) is often well-developed in paddlers, the more important, deep core stabilizers are typically inactive and overpowered by the more dominant rectus abdominis. Your attention should be focused on the development of these deep abdominal muscles to develop their activation and control.

[ Read also: 11 Easy Exercises To Make You A Stronger (And Better) Kayaker]

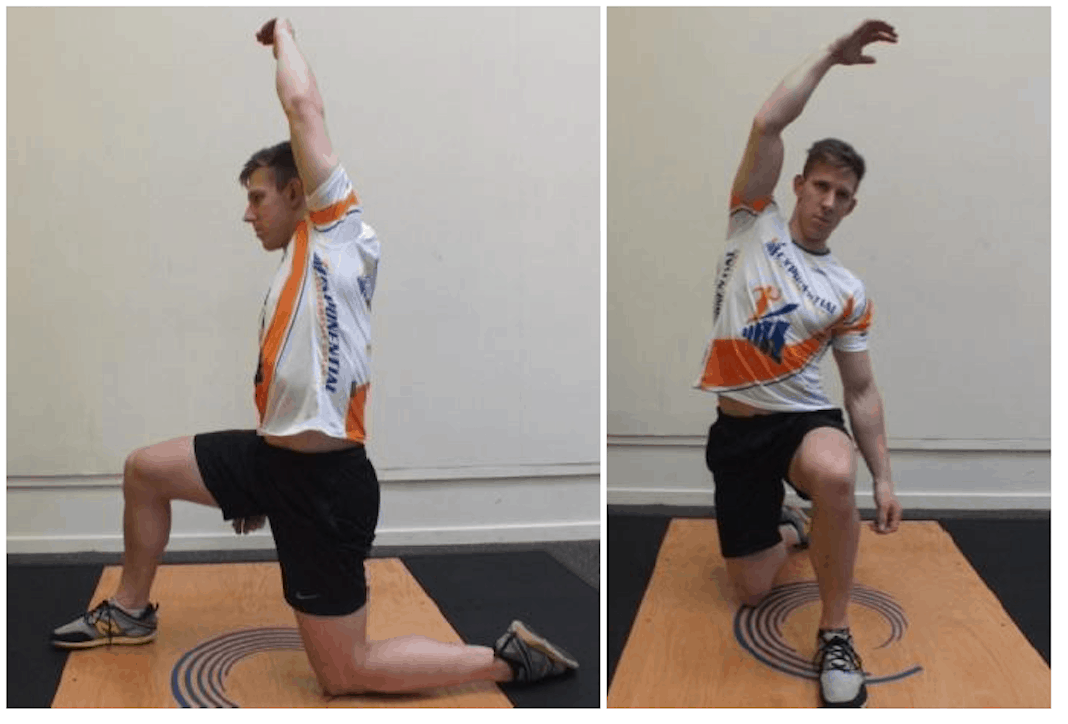

Hip flexors

The seated position and leg drive involved in kayaking coupled with prolonged sitting in day-to-day life means that paddlers’ hip flexors become very strong and tight. This often leads to lower back pain and the feeling of tight hamstrings due to a tilted pelvis. Focused stretching of the hip flexors can go a long way towards minimizing these issues.

[ Further reading: How To Avoid Lower Back Pain While Paddling ]

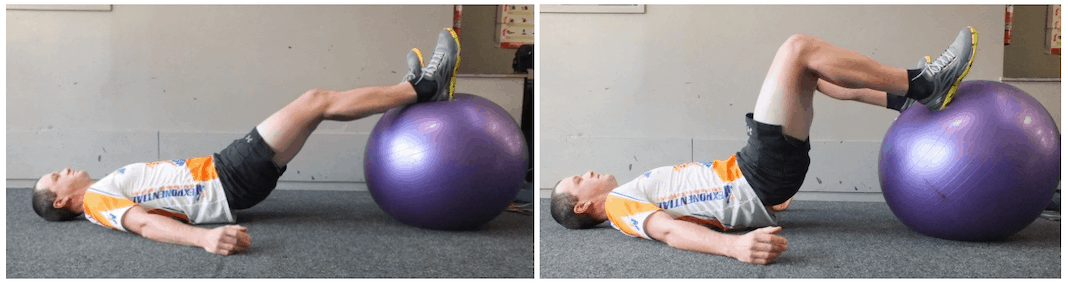

Gluteal complex and hamstrings

The muscles that form the gluteal complex and the hamstrings often become inactive and weak in kayakers. This affects postural control as well as power generation and transfer. Spending some time on developing the activation of these goes a long way.

Training phases

Introductory strength phase

During this introductory strength phase, select a weight you can comfortably lift for eight to 10 repetitions while holding good form at a controlled speed, for three to four sets. This will allow the rapid development of your strength, technique and stimulate some muscle growth in those weak green areas.

If you are new to strength training, then in the beginning, one session per week is going to be enough to see improvements

As your training progresses and your body adapts, increasing to two to three session per week will be required for you to continue getting optimal improvements.

Now that you have the knowledge, get into the gym and start your base strength development. This needs to be performed for six to eight weeks so your body develops the correct technique, structure and movement patterns to make the training you will perform in your next training phase as effective as possible.

Anatomical adaptation training phase

Now that you have completed some general introductory strength training, your body is ready to progress to the anatomical adaptation training phase. Over this training phase your focus still needs to be on refining your technique while you start to increase the amount of weight you lift. This training phase is really important to prepare your muscles, tendons and ligaments so they are able to cope with the next training phases.

During this training phase the focus is to stimulate some muscle hypertrophy, which is when your muscle fibres increase in size. A larger muscle has the potential to be a stronger muscle, so having some increase in muscle fibre size is beneficial.

Many endurance paddlers and multi-sport athletes worry about bulking up in the gym. These concerns are unnecessary as this training phase should coincide with the base endurance phase of your on-water training. The aerobic on-water training limits the amount of energy available for dramatic increases in muscle mass; therefore, endurance paddlers will not experience large gains in muscle mass.

During this training phase the load lifted is moderate (40-75% 1RM) at a moderate to high repetition range (2-5 sets x 10–20 reps, depending on the exercise) to expose the muscle to a large amount of accumulated load to “break down” the muscle fibres and trigger the hypertrophic response.

[ Watch: 8 Pre-Season Exercises For Kayaking]

Maximal strength training phase

Once you have four to six weeks of anatomical adaptation training under your belt, you are ready to progress in to the maximal strength phase. Research indicates it is this phase of your strength training that will give you the biggest “direct gains” in your performance.

These performance gains are going to occur via increases in force production through an increase in neural activation. This means you will be activating more muscle fibres, more forcefully with each muscle contraction leading to a more powerful paddle stroke.

During this training phase, the weight lifted in the exercises is increased (85–95% 1RM) and the number of repetitions is decreased (5 sets x 3-6 reps). Because of the increased weight, the speed at which the exercises are performed naturally decreases, so you end up lifting a relatively heavy weight slowly.

During this phase of your training, aim to keep your gym sessions simple and limited to a few key exercises that are going to give you the biggest bang for your buck. Compound movements that use your prime movers such as the dead lift, bench pull, bench press and rotational exercises are key during these phases of your training.

Specific kayak strength exercises

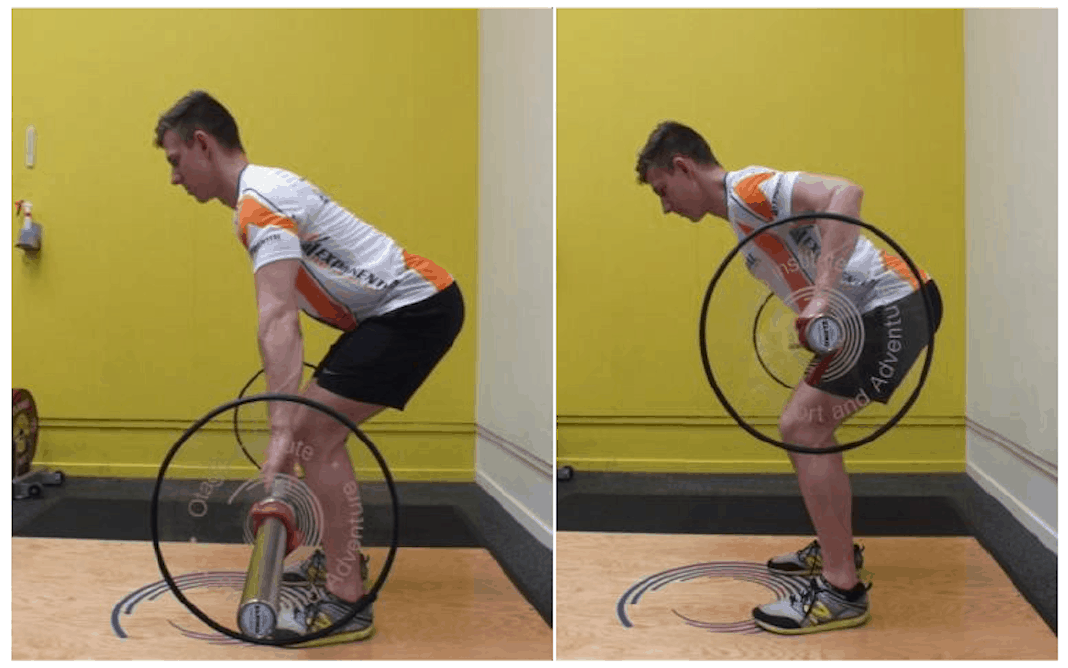

Bent-knee deadlift

Set your feet up under the barbell with your shins almost touching. Keep lower back straight in the set up, and throughout the movement. As you lift the bar, keep it as close to your legs as possible without touching on the way up. Try and open your knee and hip joints at the same time for maximum efficiency and injury resilience. Always lower the bar back down with the same technique used to lift (straight back), think of it as a “backwards lift.”

Lying barbell row

Squeeze your shoulder blades together. Try not to raise your chest off the bench. Similar to the bench press, your elbows should point away from your head. Pull the weight until it touches the bottom of the bench, then lower back down.

Bench press

Centre load directly over shoulders. As the weight comes down, push your elbows down your body towards your feet. The bar should touch your body between nipple line and sternum. Press the weight straight back up to start position in a fluid movement.

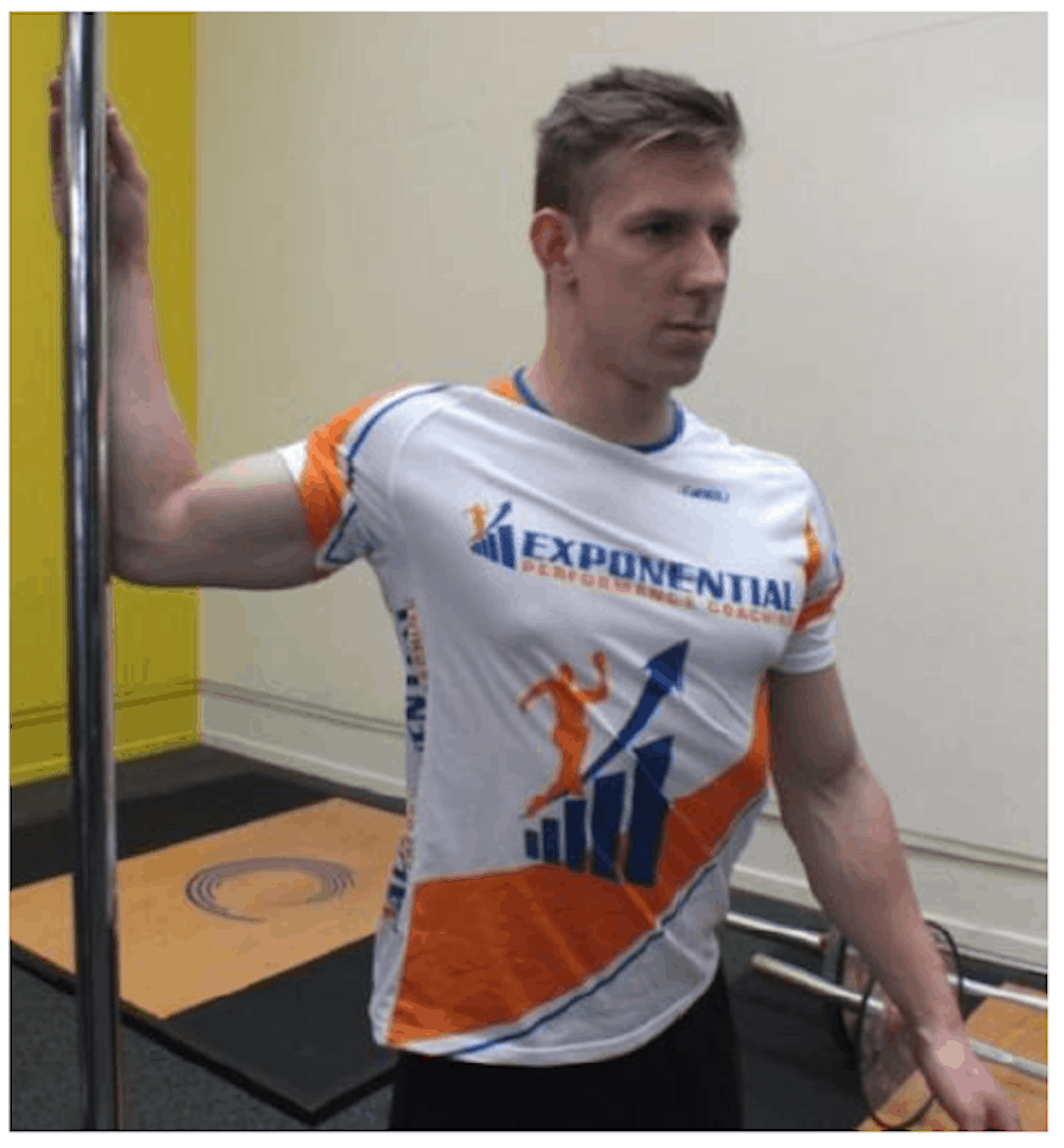

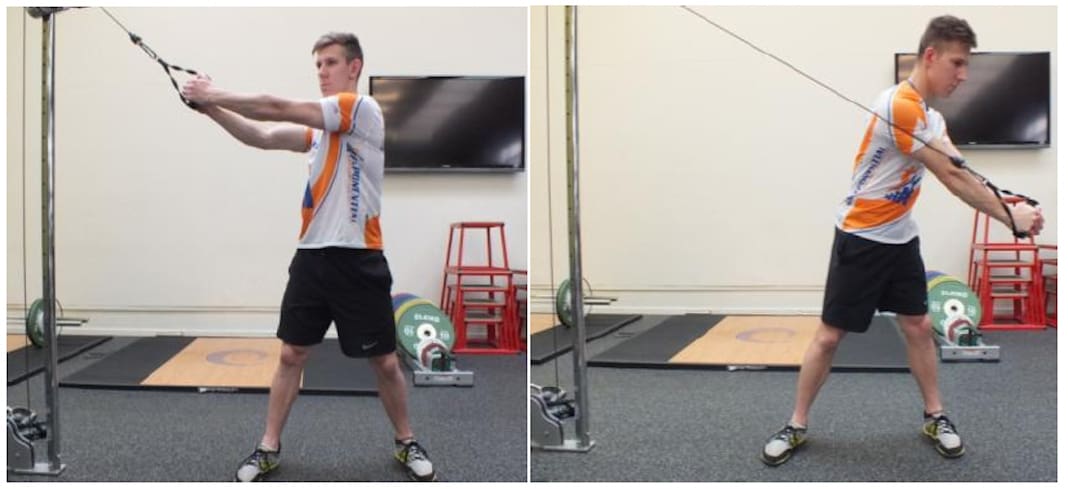

Cable cross pull

Set the cable up in a high position. Stand with your feet slightly wider than shoulder width apart and feet facing forwards. Twist your torso around to grip the handles. From this start position, rotate through your core moving your arms in an arch down to finish position. Retrace the arch with your arms back to the start position, controlling the movement with your core.

How many sessions should you have in your kayak strength training program?

The research in this area has found performance gains with a number of different sessions per week. Anywhere between two to four sessions in the gym per week is required for you to get good results from your strength training. How many times you train in the gym each week will vary depending on who you are, your training history, goals and your other training load.

I have found two sessions per week seems to works really well for most weekend warrior athletes who are balancing work, family and training. For those looking to take things up a notch and push the sharp end of the field, bumping this load up to three to four times per week on some weeks is required to get maximal results.

Great article. One strength exercise that is omitted which I find helpful in my own workout program: the one arm dumbbell row. Done with trunk exaggerated rotation, it is quite effective in strengthening and increasing flexibility in most of the major paddling muscles – including abs, lats, upper and lower back, rear delts, and arms.

I’m Fused From T4 down to L5 do rotation is a No No so I think I need to focus on shoulders and arms Seated rows, and core abs.