Delta Kayak designer Stuart Mounsey explains what makes the new Delta 15 special. Designed for a smaller fit, the kayak has a number of redesigned features, including cockpit size and new seat materials. Delta is also debuting a new hatch system using press on lids with minimal extra steps. These improvements along with other nice touches help bring the weight quite low for this style of boat.

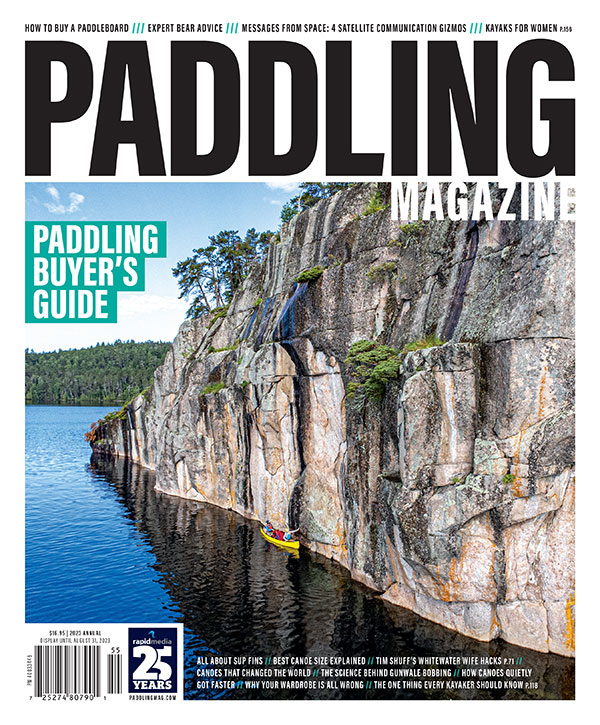

Daily Image: Island Exploration

Sander Jain photographed a sea kayaker gliding along the cliffs of grice bay’s indian island on a dark, unnaturally still January day. “The bay is a popular feeding ground for grey whales, and the scandinavian homes on indian island are a local landmark,” says Jain, whose Tofino home is just minutes from the put-in.

– Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia

Behind the Scenes at the Canadian Canoe Museum

The Canoeroots magazine crew headed down to Peterborough, Ontario for a unique, behind-the-scenes tour of the Canadian Canoe Museum. Check out this video tour of the main building as well as a few looks at what they have in the warehouse out back.

Time Travel

We’ve all been one or know one. Memorized the impossible, seven-syllable names (try saying Archaeornithomimus three times fast); pretended the backyard was Jurassic Park (and known that, to be perfectly correct, it really should be called Cretaceous park); slept between dinosaur-motif bed sheets. Yes, I’m referring to the part-time paleontologist, the fearless fossil hunter in your family. Whether it’s you, your son, grandson, sister or dad, a fascination with the creatures that walked, crawled, swam and sprouted long before we appeared can inspire a fun theme for your next family adventure.

Badland National Park, South Dakota

South Dakota’s White River Badlands are to the study and understanding of ancient mammals what Alberta’s badlands are to dinosaur research. Since 1846, paleontologists have uncovered the remains of camels, three-toed horses, saber-toothed cats, rhinos, rabbits, beavers and more, providing the most complete snapshot of mammalian life in North America during the early Age of Mammals 36 to 28 million years ago. But that’s not all. The extensive erosion that has produced this landscape of buttes, pinnacles and spires amid the prairie has also revealed even more ancient fossils dating from the cretaceous. During the Age of dinosaurs, however, a warm shallow sea covered the great plains. Since dinosaurs were land creatures, none have been found here. instead fossil hunters have unearthed giant marine lizards called mosasaurs, along with fish, turtles, nautiloids (shelled mollusks) and ammonites (ancient squid).

STAY AWHILE: Bison, bighorn sheep and prairie dogs may be seen from the park’s trails. hike 1.5 miles to the notch, a dramatic overlook of the white river valley—watch your step, the trail climbs a log ladder and skirts drop-offs.

INFO: The park is 75 miles east of rapid city on route 44. Badlands national park, 605-433- 5361, www.nps.gov/badl/

Mistaken Point Ecological Reserve, Newfoundland

Newfoundland is world-renowned for its fossils. Long ago set adrift from what is now Europe, the rock’s sheer bounty of, well, rock is home to ancient marine organisms spanning 320 million years of geologic time. Most famous of these fossil beds is Mistaken Point, a wave-battered crag that takes its name from the deadly result of sailors mistaking it for the safe harbor of cape race. Buried in fine volcanic ash 565 million years ago, the creatures now exposed here in tennis court-sized slabs of sea cliff are not only the most ancient deep-water marine fossils in the world, they’re also the oldest diverse collection of complex organisms ever discovered. And they’re controversial, too. Only a handful of the frond-like, leafy forms resemble known living animals— most are so radically different that some scientists insist on assigning them to their own completely separate kingdom.

STAY AWHILE: Reached by dirt road and a six-kilometer hiking trail on the tip of the Avalon Peninsula, Mistaken Point has an edge-of-the-world feel that’s worth visiting even if you’re not a fossil buff. Between June and September, don’t pass up a whale- and puffin-watching boat tour 90 minutes north in Witless Bay.

INFO: The point is two hours south of st. John’s, off route 10. Meet your guide at the interpretive center in the coastal village of portugal cove south for a daily tour (departs 1 p.m., May–October, 3–4 hours). 709-438-1100, www.env.gov.nl.ca/env/parks/wer/r_mpe/ index.html

Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta

When dinosaur fanatics dream of Nirvana it looks a lot like southeastern Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park. Here the Red Deer River Valley carves through Canada’s largest badlands, revealing haunting hoodoos, isolated mesas and the greatest concentration of Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils ever found. Every known group is represented, including favorites like Triceratops, Hadrosaurus, The Lost World’s battering ram Pachycephalosaurus and, of course, the terrifying Tyrannosaurus rex. Seventy-five million years ago, this was low swampy country with a steamy subtropical climate, and the dinosaurs rubbed shoulders with fish, turtles, crocodiles, amphibians and even marsupials. Since the first paleontologists began digging here in the 1880s, more than 23,000 fossils have been collected, including 300 dinosaur skeletons. Some of these now reside in museums around the world, but the greatest collection is housed just a two-hour drive away in Drumheller, Alberta’s Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology.

STAY AWHILE: explore the stark beauty of the badlands on the six-kilometer Great Badlands hike. Join one of the park’s paleontologist-led family or kids’ day programs, including an authentic dinosaur dig, prospecting hike or dinosaur day camp.

INFO: The park is three hours east of Calgary, off route 544. Dinosaur Provincial Park, 403-378-4342 ext. 235, www.albertaparks.ca/ dinosaur.aspx

Burgess Shale – Yoho National Park, British Columbia

The word Yoho comes from the Cree language. Probably the best translation is “wow”. Native peoples and modern visitors exclaim at the stupendous Rocky Mountians, emerald lakes and 833-foot Takakkaw Falls (another Cree word meaning magnificent). But it is likely that paleontologist Charles Walcott also breathed “wow” in 1909 when he discovered the fossil bed now known as the Burgess Shale. in seven years, Walcott collected more than 65,000 fossils, many of which were unknown. Declared a World Heritage site in 1981, the Burgess Shale is still regarded as the finest site for Cambrian age fossils. Join a daylong guided hike—the only way to view the park’s two fossil beds—to learn how these half-billion-year-old marine animals hold important clues to evolutionary understanding. Mount Stephen’s famous trilobite beds are accessed via a nine-kilometer hike, while walcott quarry is a strenuous, 22-kilometer round-trip to a spectacular subalpine ridge.

STAY AWHILE: There’s no shortage of things to do in Yoho. View some of the park’s abundant wildlife and lofty peaks while hiking one of the dozens of trails, canoeing on aptly named Emerald Lake or staying at a historic backcountry lodge.

INFO: The park is a short drive west of Lake Louise on Trans-Canada Hwy 1 and borders Banff National Park to the east. Yoho Visitor Center, 250-343-6783, www.pc.gc.ca/eng/pn- np/bc/yoho/natcul/burgess.aspx

What is a fossil?

Think of fossils and the first thing that comes to mind is probably a dinosaur skeleton. But fossils come in every shape, size and age—the oldest fossils are 3.5-billion-year-old stromatolites while the youngest are just 10,000 years old.

Mold and Cast Fossils form when a skeleton is buried by sediment. Over time, the sediment turns to stone and the entombed bones begin to dissolve, leaving a cavity in the shape of the original skeleton. Water rich in minerals enters the cavity and the minerals deposited in the mold form a cast that has the same shape but none of the internal features (or DNA) of the original skeleton. Most of the fossilized bones, shells and leaves we find are mold and cast fossils.

Replacement Fossils are made up of minerals that have taken the place of the original organic material while preserving the internal structures. For example, petrified wood is actually rock—silicon or calcite crystals have replaced all of the organic matter down to the last cell!

Whole Body Fossils are unaltered, intact organisms like mammoths caught in ice or tar pits, or insects trapped in amber.

Trace Fossils record the activity of an animal, rather than the animal itself. These include footprints, tracks and coprolites (fossilized poop!).

This article first appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

S-Turn Rapid Technique

This whitewater kayak technique article originally appeared in Rapid magazine.

S-Turn is one of the most famous and celebrated rapids in Mexico. It is the crux rapid on the notorious Roadside section of the Rio Alseseca, dropping 20 fast and twisty feet before ending in an eight-foot-wide mini gorge.

As with any steep, tight drop the first requirement for hitting your line is staying upright. The real trick to nailing S-Turn, however, is to get river right during the first slide. Although it looks like a bad idea, starting left is the way to go. Then the water will take you back to the right at the correct time.

[1] Enter the rapid on the far left with your bow pointed slightly right. This will look intimidating since there is a menacing rock wall on the left that if feels like you are going to crash into. In reality, you will slide down four feet, hit the angled rock on the left and deflect back with right momentum.

[2] Take a hard left stroke to pull yourself as far right as possible onto the ridge of dry rocks that form the top bend of the “S”. Your bow should launch off the rock, sending your boat into the air. This move is key, as it sets you up for the next turn. If you don’t make it all the way right, your bow will drop and could piton the left wall, which will most likely result in a flip. Avoid this at all costs!

[3] Once you have launched off the rock and are aerial, lift your left knee. This prevents you from flipping when you land on the large boiling curler coming off of the left wall.

[4] Brace as required to stay upright and take a powerful right stroke to keep your bow pointed left as you enter the final kink of the S-turn. If you fail to keep your bow left here, you risk spinning out into a micro eddy on the right or spinning sideways and pinning in the narrow alleyway below.

[5] After you have snaked through the sliding S-turn, you drop into the super cool mini gorge. This alleyway is about 70 feet long with 15- to 20-foot-high walls. Make sure to stay pointed downstream because, at just eight feet wide, the gorge is the perfect size to pin sideways if you get careless. Enjoy the view as you drop out of the alley into a calm pool.

[6] When you realize that this is one of the coolest rapids EVER, you can eddy out on the left in the bottom pool and hike back up for another run.

– Nick Troutman was a member of the first team to make a full descent of the Rio Alseseca. He swam three times and considers himself lucky.

This article originally appeared in Rapid, Fall 2012. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions