Greenland rolling has its origins in the deep survival skills of Inuit hunters plying frigid Arctic seas. The ability to recover from any capsize, in any conditions, was a matter of necessity.

While there are some 35 different Greenland rolls, most are variations of a handful of fundamental rolls. You may want to know these more esoteric options for those occasions when, for example, you’ve had your fingers chomped by a vicious leopard seal (crook-of- the-arm roll) or become ensnared in your harpoon line (straightjacket roll).

But in our experience, mastering just three rolls—the standard Greenland roll, reverse sweep roll and storm roll—will empower you to recover from any capsize where you keep hold of your paddle.

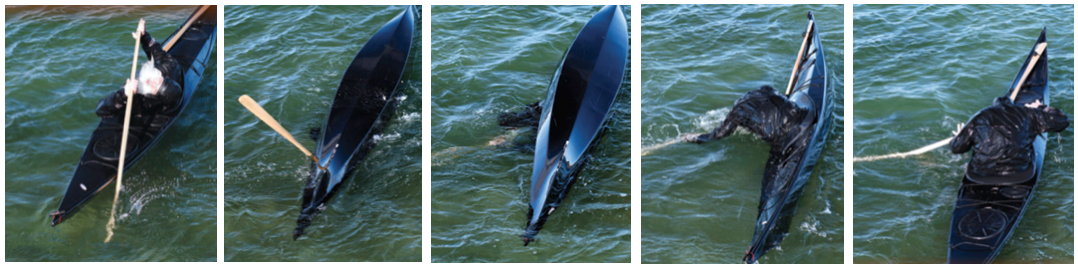

Standard Greenland Roll

The Standard Greenland roll is the easiest of the three rolls to learn. Performed with an extended paddle for added leverage and flotation, it can be done slowly, giving you more time to think. Once dialed, it can be executed with your hands in a normal paddling position. This roll is the foundation for all other aft finishing rolls.

- Extend your paddle, gripping the blade shoulder-width apart. Rotate, hold the paddle alongside your kayak and tuck tightly forward to this side. Capsize and hold the tuck.

- Pause and let the paddle float to the surface. Maintaining your tuck, move your pivot hand—the hand closest to the stern of the boat—to your pivot shoulder. This hand is like the center of a clock, it anchors to the pivot shoulder and stays with that shoulder throughout the roll. The pivot hand also sets your blade angle, so be patient with your sweep until it is in place. Now your body is ready to uncoil.

- Uncoil your body, rotating onto your back just as you would float on your back while swimming. Engage your core muscles to get your shoulders parallel to the surface. The back float is key— utilizing the natural buoyancy of your body, it allows you to gain support from the water to leverage the kayak upright. As you uncoil, keep your pivot hand at the pivot shoulder and open that hip while driving up with your water (or lower) leg. The sweep shoulder moves up toward your sweep hand, finally meeting on the surface. Resist the urge to pull downward as you sweep.

- To finish the roll, arch your back, drop your head back deeply into the water and continue to drive up with your water leg. Engage your abdominals and lift your body out of the water onto the back deck. At this point, both of your hands are facing palms up at your shoulders and the paddle is perpendicular to the kayak.

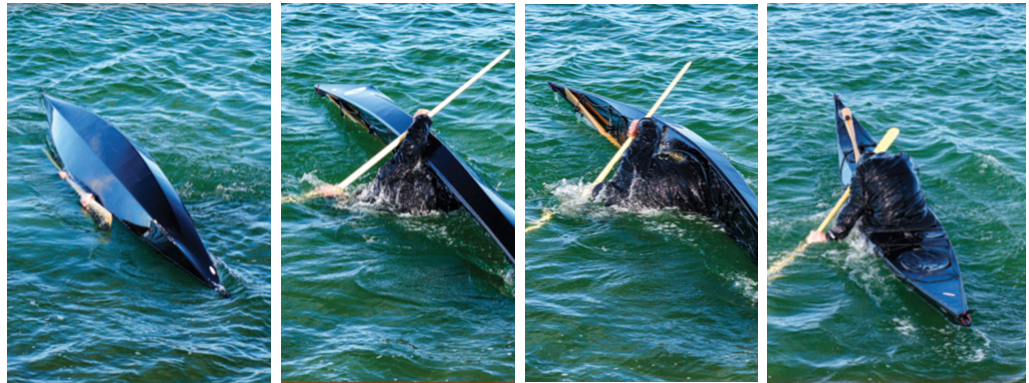

Reverse Sweep Roll

The reverse sweep roll starts with your body rotated and arching back, and finishes with your chest tucked forward over the front deck. The roll is essentially the opposite of the standard Greenland roll; while you again use an extended paddle and your body’s natural ability to float, you move the blade in the opposite direction and float face down. This roll is useful anytime you find yourself capsized to the back deck, as often happens while surfing or if you’ve just blown your standard Greenland roll.

- Extend the paddle, holding it with hands shoulder-width apart and palms facing upward. Rotate your body, look- ing back toward the stern, and place the extended paddle tip beyond the opposite gunwale.

- When you’re ready to capsize, archback and use your core muscles to maintain this position with the paddle tip pinned to the gunwale. After capsizing, pause here with the top of your head sticking out of the water, close to your stern gunwale. The extended paddle tip should be out of the water, on the same side of the kayak as your head. Extend your pivot hand, on the other tip, straight down underneath your body. Bend your sweep arm and hold this hand close to your forehead without weighting the paddle. Arch your back— think cow pose in yoga—with both shoulders horizontal to the surface.

- Sweep forward with your body, face down and shoulders horizontal, keeping the pivot hand below you and the sweep hand near your forehead. As you sweep toward the bow—body and blade in concert—drive up with your water leg.

- Continue until your head, torso, and paddle are 90 degrees to the kayak, and then transfer the weight from your pivot hand to your sweep hand. Straighten that arm, pushing your sweep hand away from your face and driving the sweep blade down. Rounding your back—think cat pose in yoga—drive your head down with the paddle. Continue engaging your water leg.

- At this point the kayak should be mostly upright and your head and sweep hand deep in the water. To finish, pull the paddle inward across your lap with even pressure on both hands, and bring your body over the front deck.

Storm Roll

The storm roll is the best rough water roll. It requires minimal set-up and is very quick. Use it to paddle out through heavy surf—you start and end tucked forward so your head stays protected the whole time. As soon as you finish the roll, you are looking forward and in position to paddle quickly or roll again if needed.

- Hold the paddle with your hands in regular paddling posi- tion. Rotate, tuck forward and reach both hands as far over the side of your kayak as possible, pressing the paddle faces to the hull as you capsize. Maintain your tuck with your face looking at the sky and continue reaching both hands around the bottom of your kayak. Push the paddle past the chine, toward the keel.

- Your stern hand is now your push hand. This hand pushes down and forward along the kayak, using the hull to set an effective sweeping blade angle. The push hand moves from behind your hip at set-up to the foredeck at the finish, pressing the paddle hard to the kayak the whole time. Your forward hand is your sweep hand—as you push with your stern hand, you pull with your sweep hand. Don’t weight this hand; just sweep it along the surface.

- As soon as you start to sweep, drive up hard with your lower leg. Don’t put any pressure on the other leg—if you find your- self engaging this leg, take it off the foot support or drive it into the bottom of the kayak. As your sweeping blade reaches perpendicular to the kayak, rotate your head to face down at the opposite gunwale, keeping your shoulders parallel to the surface.

- The sweep ends just past 90 degrees with your body tucked tightly to the front deck. If your sweep angle isn’t quite right, you may need to add a pry or low brace at the end of your roll.

Cheri Perry and Turner Wilson are featured in a brand new instructional DVD, This is the Roll. Get it at cackletv.com.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2012 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2012 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.