We began our trip as Debside invariably does: at the bus stop.

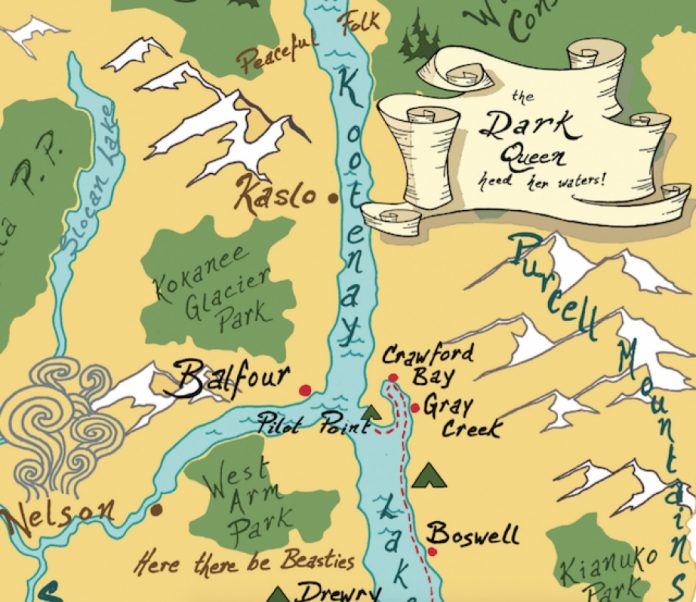

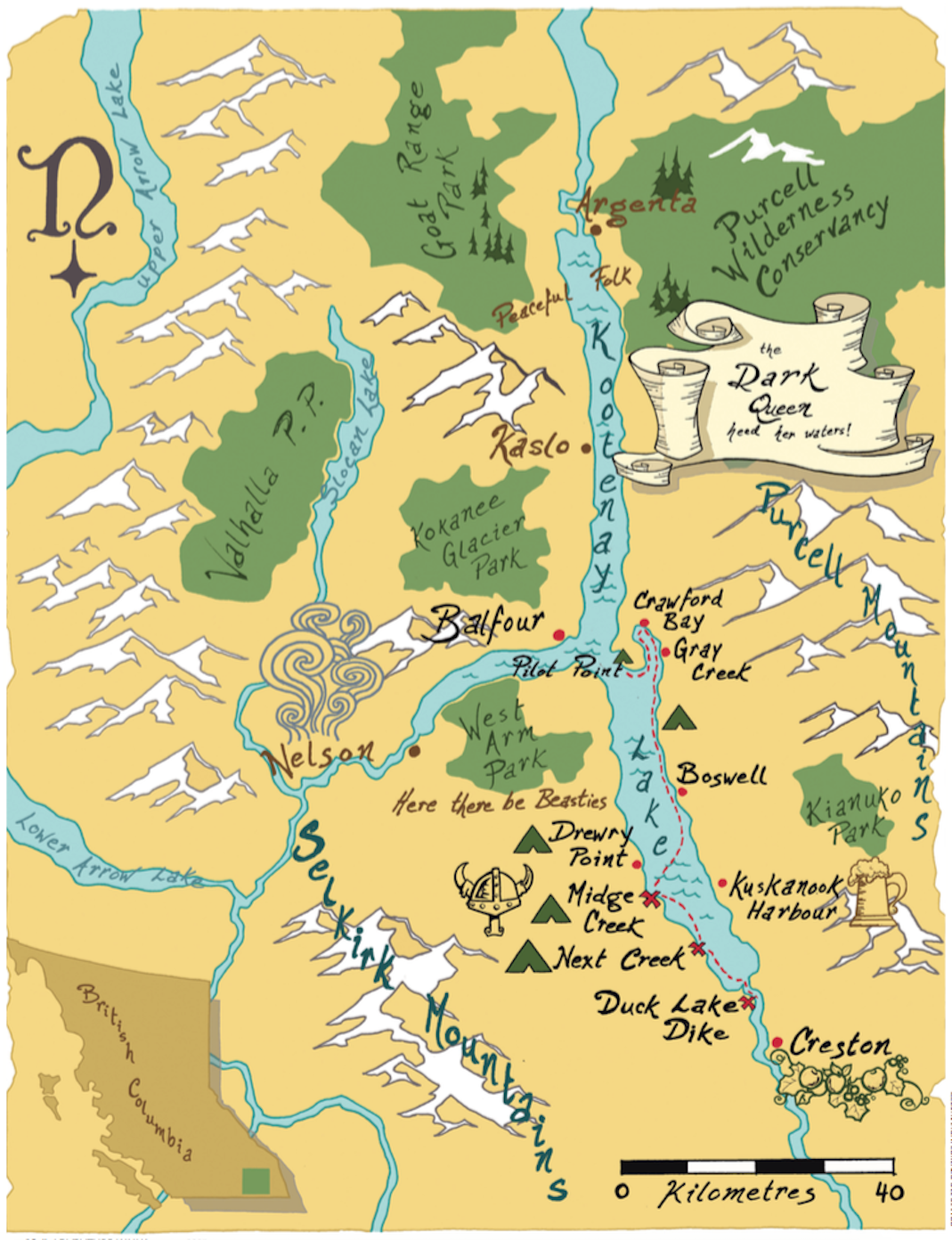

I followed as he dragged the black bag containing his folding kayak and paddling gear on its wheeled frame past the children’s playground to a fence overlooking Puget Sound. There we paused while he pulled out a coloured map.

“Here’s this put-in.” His finger identified our location. “At the bottom of this hill, there should be a footbridge.” Moving his finger to indicate another spot on the map where the road curved close to the water. “I thought this place might be good too but when I checked it out, there’s no way to get across the rail tracks. You have to think of that sort of thing when you choose put-ins. Bus routes….” He held up his timetable, and a map. “You don’t want to cross private land either—it would give kayakers a bad name—but there are often little public access places to the beach if you look for them.”

We followed the fence to a corner where wooded land dropped steeply to a creek, and then as we backtracked we ran into a dog walker who pointed us in a different direction, back to the road to cross the creek. There in the bushes we found the top of several steep flights of steps.

The thud of descending wheels gave way to their steady rumble as we crossed the caged walkway high above the rail tracks and rolling stock. As we spiraled down more steep steps toward the beach I reflected how awkward a carry this would be with a rigid kayak, even with two people, yet how comfortably Dubside dealt with it.

WHAT IS DUBSIDE?

Dubside’s lifestyle package began in Philadelphia. Into the reggae scene, which incidentally inspired his famed dreadlocks, he worked as a sound engineer for bands. Living inexpensively in a single room in a house with a shared bathroom, no outside yard space, no car, no vices, he found he needed to work no more than two or three days a week to cover his expenses. Valuing time over money, for most of each week he was free. In 1998 he discovered kayaking.

Dubside’s lifestyle package began in Philadelphia. Into the reggae scene, which incidentally inspired his famed dreadlocks, he worked as a sound engineer for bands. Living inexpensively in a single room in a house with a shared bathroom, no outside yard space, no car, no vices, he found he needed to work no more than two or three days a week to cover his expenses. Valuing time over money, for most of each week he was free. In 1998 he discovered kayaking.

Canoeing as a kid introduced him to access to wildlife spots and special moments even in the middle of the city. It offered a different, magical perspective. But to take up kayaking now Dubside faced a radical change to his lifestyle. If he were to buy a kayak, a car to carry it with all its running expenses, and find a place to store his kayak, that could require a full-time job which would leave him little time to paddle. Then he ran into Ralph Diaz at the New York Kayak Company, a lifetime advocate of folding kayaks. Dubside was inspired to mail-order one, sight unseen.

Reaching the beach, Dubside looked around for a place to assemble his kayak.

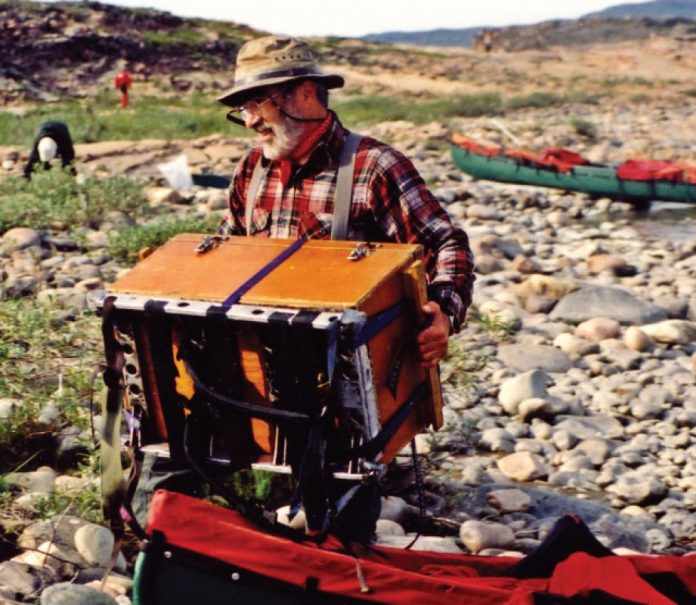

“I try to find grass so I don’t get sand and stones inside the skin.” From his black package he unfolded a 16-foot-long black rubberized kayak skin and a pile of aluminum tubes and plastic frames. “When I got my first kayak it took me more than an hour to assemble it. Now it takes fifteen minutes.” My own first attempt to assemble a Feathercraft, out in the Queen Charlotte Islands, had been a puzzling experience. Setting out then on a multi-day camping trip rather than Dubside’s more usual day or night trip, I never did trim my time to less than an hour.

As Dubside inserted sections of frame and his kayak began to take shape, he continued, “Then there’s the safety aspect. I can paddle during the week when most people are at work, so I mostly went solo. My first kayak was so wide and stable most people said it wouldn’t capsize, but then I got a nar- rower one and I wanted to learn how to roll, for safety, especially as I often paddled in winter. Sometimes there was ice on the water. At the pool sessions the other paddlers were Greenland-style enthusiasts, so they taught me to use their paddles, and I got into the whole Greenland stuff, with its emphasis on a wide range of different rolls. The ropes tricks? That came as part of the same pack- age. Helps to keep you flexible and fit too!”

Too modest to volunteer his success in competition, Dubside neglected to add that he is regarded as one of the world’s most highly skilled performers of both Greenland rolls and of Greenland rope gymnastics. All this in so very few years, he says, because his lifestyle allows him so much time on the water.

DUBSIDE ON ACCESSORIZING

Dubside now peeled off the black boiler suit he’d worn on the bus to reveal a black drysuit underneath. He struggled into his neoprene tuilik. Sealed around his face so tightly, this combination of spray deck and anorak almost completely excludes water when he rolls.

He clipped his pump to his deck and a VHF radio to each shoulder. He laughed

as he explained how he used to give talks about radios. He bought several for the purpose, so now he often carries two, one for monitoring all channels, and the other on a fixed channel to listen for specific conversations. “If I hear ferry or tugboat captains warn of a kayaker in the channel I can call back and say it’s me. That makes everyone more comfortable.” He assembles his paddle and he’s about ready to go.

Paddling beside me across gentle waves, Dubside played at what he likes best, rolling. He surfaced each time with a big smile on his face admitting that it is difficult for him to stay upright. That’s not because he doesn’t have the skill to do so. “Even when I decide to stay dry for a day, I always end up rolling a few times because I enjoy it so much!”

STEALTH IS ESSENTIAL

As we cross the channel to Whidbey Island he points this way and that, identifying places where he knows he could put in or get out. Relatively new to the Northwest, he’s becoming familiar with it. In time he might know it as thoroughly as Philadelphia, where he would decide on the best access and egress points depending on the weather, or if it was daylight or not. There were some intimidating places he felt he could land and take apart his kayak hidden by the vegetation of the bank without attracting unwelcome attention. He could not do the same when launching because people would follow him into the bushes. He’d felt vulnerable surrounded by hostile kids with his kayak only part assembled.

“Stealth paddling! That’s what I often did in Philly!” I could understand why the coast guard and police so often challenged this figure clad completely in black as he crept around the channels at dusk and lurked in the bushes.

Perhaps here in the friendly Northwest, he can be more relaxed. “All the Whidbey Island transit buses offer rides for free, and the ferry doesn’t charge passengers on the way back off the island. So, depending on the weather, I could change my plans and go over there, or over there, and catch a bus and ferry back to the mainland to get my bus home. That flexibility offers me more safety, more options if conditions are not how I expected. It doesn’t matter where I come ashore; I just pack up my kayak, look up the bus routes and timetables and figure out a way home.”

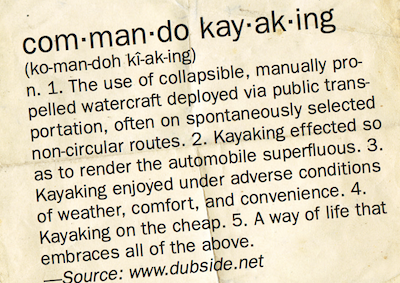

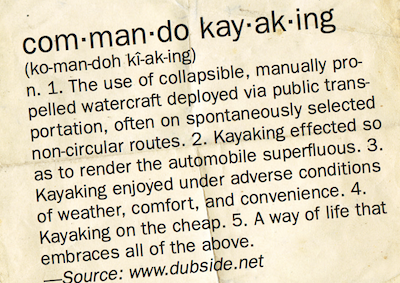

Taking advantage of that flexibility and independence is the style of operation Dubside refers to as “commando kayaking.”

Asked what he would change in his lifestyle, if he could, Dubside considers for a while before answering. “Maybe better mass transit. Perhaps if I moved closer to Seattle where the buses would run later, I’d have more options.” We drift while a ferry crosses our path on its way to dock. “We could catch that one if we pulled out the stops,” he says, eyeing up the distance left to paddle and calculating the time it would take to fold his kayak and wheel it aboard. But neither of us feels the need to rush.

MAN WITH A MESSAGE

I ask if he preaches his lifestyle. “Not exactly. But you know, although a Feathercraft is an expensive bit of kit, you don’t have to have a lot of disposable income to enjoy paddling. If you don’t have a car, don’t have anywhere to store a kayak, don’t have much income, you can still do it. And that goes for adventure too. The media love to glorify the exotic places people go to paddle, but really, adventure can be anywhere and everywhere. You don’t have to go far to find it. Water freezes, there are eagles and wildlife dramas, you see tugboats and find out where they go, you get familiar with where the low-tide rocks are so you know where not to roll. There’s magic in the mist. Knowing an area intimately through different times of day, different tides and different sea- sons, with all the possible landing places and ways to get home from wherever you go—that’s something very special a tourist visiting an exotic location for a short time will never know.”

As he spoke, I was reminded of my early kayaking days. As a 16-year-old I walked my canvas kayak on a homemade trolley down two miles of winding hill

to the coast near Brighton each time I wanted to paddle. Less versatile than a kayak I could carry on the bus, the rigid kayak on wheels yet offered me independence, the chance to escape to the English Channel, the door to the adventure I am still having.

I have to ask one more question. What about a life partner? I knew his answer before he replied. Not married yet, still looking for that perfect kayak wife. I don’t know who she will be, but I can imagine how she will be.

As Dubside wheeled his anonymous black bag from the ferry, I reflected on what I saw, and on what I knew. I saw

an inconspicuous small figure in black dragging a bag, walking with the crowd up the landing ramp. I knew that particular one in the crowd as a committed kayaker, who tailored his life to fit his dream, not tailored his dream to fit his life. He is now producing instructional DVDs and booklets. He is invited to demonstrate and teach rolling at sea kayaking events. He is finding the way to do what he enjoys in a way that is in harmony with his ideals. I can relate to that.

It’s true, you don’t need much money. You just need to take the time.

Nigel Foster is an international figure in sea kayaking.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

Dubside’s lifestyle package began in Philadelphia. Into the reggae scene, which incidentally inspired his famed dreadlocks, he worked as a sound engineer for bands. Living inexpensively in a single room in a house with a shared bathroom, no outside yard space, no car, no vices, he found he needed to work no more than two or three days a week to cover his expenses. Valuing time over money, for most of each week he was free. In 1998 he discovered kayaking.

Dubside’s lifestyle package began in Philadelphia. Into the reggae scene, which incidentally inspired his famed dreadlocks, he worked as a sound engineer for bands. Living inexpensively in a single room in a house with a shared bathroom, no outside yard space, no car, no vices, he found he needed to work no more than two or three days a week to cover his expenses. Valuing time over money, for most of each week he was free. In 1998 he discovered kayaking.