For the canoe tripper, parks present a dilemma.

On one hand, park services such as information staff, route maps and marked campsites and portages can make planning and executing a trip a simple affair.

For the canoe tripper, parks present a dilemma.

On one hand, park services such as information staff, route maps and marked campsites and portages can make planning and executing a trip a simple affair.

On the other hand, the simpler the planning is the more likely that the route will be crowded and you’ll be plagued by a feeling of being watched by park authorities.

By digging a little harder than the average park visitor you can still find routes that are unfairly neglected.

Every park has a corner that is hard to get to or a lake in the middle that requires a tough carry to reach. Here we offer four routes that enjoy all the ease of park tripping and all the seclusion of a forgotten piece of Crown land that only you know about.

Clearwater-Azure

Alpine wildflowers, old growth rainforest, extinct volcanoes and snowy peaks are not the typical scenery of a canoe trip. Clearwater and Azure Lakes provide an ideal setting to soak up several days of B.C. wilderness. If the stunning views aren’t enough, the route offers great campsites, sandy beaches, a river section, and, in addition to the standard-issue moose and eagles, the Clearwater-Azure route is home to grizzlies and mountain goats.

Wells Gray Provincial Park comes by its nickname of “the waterfall park” honestly, and Rainbow Falls is your proof toward the end of the steep-sided, glacier-fed Azure Lake. If you tire of the falls, forest and beach, explore the wetlands up the mouth of the Azure River.

Need to know

The trip begins and ends at the south end of Clearwater Lake, where you self-register and pay five dollars per person per night (cash only, kids under 13 are free). The lakes, each about 25 kilometres long, are joined by a three-kilometre section of river and a 500-metre portage. On the paddle up the Clearwater River, watch for the portage on your right. On your return trip, enjoy the downstream ride.

Powerboats are permitted on the lakes, but boat traffic is not a major detractor, especially if you go in June or September, and at low water fewer powerboats travel into Azure. Both lakes have campsites (Ivor Creek and Osprey) that are designated for canoeists.

Info

Wells Gray Information Centre: Clearwater, B.C., (250) 674-2646, env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/parkpgs/wells.html

Park Facility Operator: (250) 674-2194, explorewellsgray.com/index.html

Maps

Download a map from the B.C. Parks Wells Gray website. Additional topographic maps are not necessary for canoeing. env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/parkpgs/wells.html

Outfitter

Clearwater Lake Tours: (250) 674-2121, clearwaterlaketours.com

Probably didn’t know

Wells Gray was set aside in 1939 to protect an area almost as large as Prince Edward Island. It has since become an important refuge for the increasingly threatened mountain caribou. Much of their low-elevation habitat outside of the park has been lost. Caribou are often munching away on the forested slopes south of Azure Lake.

Need to bring

Bring sturdy hiking shoes and a comfortable pack so you can make the full-day hike up to Huntley Col (six kilometres, five hours one way, 1,300-metre elevation gain). You could also plan an overnight hike to Hobson Lake, where Clearwater Lake Tours also rents canoes (15 kilometres, 7 hours, one way, 300-metre gain). Either sidetrip could justify another few days in Wells Gray.

—Patrick Yarnell

Pine Loop

Quetico’s forest is primarily spruce, balsam fir and jack pine. But when you come upon a red or white pine rooted along any of the park’s 600 lakes, you’re in for a treat. Most of the pine stands average around 340 years old, making them some of the oldest trees growing on the Canadian Shield. And one of the best patches of trees to go and see are the ones found on Shan Walshe Lake.

The lake was named after a park naturalist that the Thunder Bay Chronicle called “the conscience of Quetico.” Visiting this lake, and the forests he slowly convinced others to protect, is a perfect way to spend a week in a canoe.

Need to know

The access point for this five-day loop is Ely, Minnesota, meaning a quarter of the route is in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA), one of the United States’ largest chunks of protected wilderness.

Drive northeast out of Ely (and while there, be sure to pronounce it Elee, with an emphasis on the first syllable, or incur the wrath of otherwise friendly Elyians). Take Highway 169 (Fernberg Road) and then Moose Lake Road. It’s 31 kilometres from Ely to the public launch on Moose Lake. From there you paddle half a day across Moose, Newfound and Sucker Lakes to reach the Canadian border. To legally cross the 140-metre Prairie Portage in either direction, Canadian and U.S. paddlers must have a Remote Area Border Crossing permit. The route then heads clockwise through a chain of lakes linking Basswood, South, West, Shade, Dell, Grey, Armin, Shan Walshe, McNiece, Kahshahpiwi, Side and Isabella lakes, which brings you back to Basswood’s North Bay.

To obtain a Remote Area Border Crossing permit download an application at queticopark.com/rabc/. Canadians can also contact the Canada Immigration Centre, (807) 624-2158. The permit costs $30 Cdn and takes four to six weeks to process. Each paddler must have one.

Info

Quetico Provincial Park: (807) 597-2735 (Trip Planning Information Line).

BWCA home page: bwca.com

The route is written up in A Paddlers Guide to Quetico and Beyond, by Kevin Callan, (Boston Mills Press/Firefly Books).

Maps

The Friends of Quetico canoe map costs $14.95 and can be ordered from (807) 597-2735 or purchased at a ranger station.

Canadian topographical maps: 52 B/3, B/4, B/5, B/6.

U.S. fisher maps: F-10, F-18, F-25.

Outfitters in Ely, Minnesota

Canoe Country Outfitters: 1-800-752-2306, canoecountry.com/canoecountry/

River Point Outfitting: 1-800-456-5580, elyoutfitters.com/index.htm#si

Canadian Waters Canoe Outfitters: (218) 365-3202, canoecountry.com/canadianwaters/

Probably didn’t know

The portages leading in and out of Shan Walshe and McNeice lakes aren’t easy. One kilometre-long carry descends into a swampy bog then climbs up a nearly sheer slab of rock. But it’s worth it because it was this rugged terrain that kept the loggers from getting there in the first place. The pine were eventually scheduled to be cut in the 1960s but by then there were so many politically active paddlers who knew about them that the cutting was stopped.

Need to bring

An eye for the weather and a good rain tarp. Quetico is well known for its sudden rain squalls and frequent lightning storms.

—Kevin Callan

Chochocouane River

Before we get a letter of correction from the Official Languages Commission, we should point out that réserve faunique does not, strictly speaking, translate into English as provincial park. It’s true that there is hunting and logging in La Vérendrye, but they also occur in some so-called parks, and La Vérendrye has a maintained network of canoe routes that puts most parks to shame. For 15 years Canoe-Camping La Vérendrye (CCLV) has made tripping on the 800 kilometres of routes crossing the 13,615-square-kilometre reserve a simple affair.

Need to know

To paddle the Chochocouane, the reserve’s biggest river, you will want to follow circuit 61, a loop of 65 kilometres, or circuit 63, a variation that traverses 132 kilometres.

But wait, you say, how does a river trip constitute a loop? You have to ascend the Canimiti River at either end of the loop for a total of 31 upstream kilometres. At summer levels the current should only be noticeable for 10 kilometres and it means you won’t have to arrange a shuttle.

The put-in and take-out for both loops is the bridge on the Canimiti River, 113 kilometres northwest of Le Domaine, the CCLV visitor’s centre on Highway 117. The amount of the Chochocouane you descend will depend on which loop you choose, but either section offers plenty of easily avoided whitewater, making it suitable for any skill level.

Permits and fishing licences are available at Le Domaine. Permits for each circuit are handed out on a first-come, first-served basis every day.

Info

You can learn everything you need to know from CCLV (819) 435-2521, canot-camping.ca.

Maps

CCLV: Map #6 (order for $8 through the website).

Topographical: 31 N/11, 31 N/14, 31 N/15.

Outfitter

Rent canoes at the CCLV base at Le Domaine. You can also arrange a shuttle if you want to spare your vehicle some logging road travel. A round trip from Le Domaine for two canoes or less is $226.

Probably didn’t know

You don’t need to own a car or freeload off your friends to paddle La Vérendrye. Le Domaine enjoys daily bus service from both Ottawa and Montreal, both less than 350 kilometres away. Once at Le Domaine you can pick up your rented canoe and pre-arranged shuttle. Bus from Montreal, $109, (514) 842-2281. From Ottawa, $106, (613) 238-5900. Schedules are posted on the CCLV website.

Need to bring

Your dog. Though some restrictions exist, Sparky is welcome in La Vérendrye.

—Ian Merringer

New Northern Loop

In the 1990s the Ontario government conducted public consultations named Lands for Life. The result was an increase in the number and size of provincial parks. For the Killarney area it meant new parkland would reach up and grab Lake Panache and environs within its protective embrace.

But the wheels of land use management turn slowly, too slowly for Kevin Callan. In the spring of 2005 and 2006 he explored the park’s new territory, searching for “lost” portages and routes the park could use. Not only did he find some, he even recorded them for the park staff who went out last season and “re-discovered” them. What they have yet to do, however, is to create a reservation system for the new extension, meaning you won’t have to take your Palm Pilot to ensure you get to all your appointed campsites on time as you explore the rugged land north of the La Cloche mountains.

Need to know

Strictly speaking, the route is not in Killarney proper but in a new park called Killarney Headwaters and Lakelands Provincial Park. It doesn’t receive the same level of protection as Killarney itself, but administration and management are done from the same park office. You still have to get a park permit, but not reservations for specific campsites.

Start this loop either at Lake Panache Marina or Walker Lake public launch. To reach the marina, drive south on Regional Road 55 from Highway 17, about 30 kilometres west of Sudbury. After 1.5 kilometres turn right onto Regional Road 10 and drive south to Lake Panache. For Walker Lake public launch drive south on Highway 6 through Espanola and turn left on Panache Lake Road (Queensway) directly across from the Tim Hortons coffee shop. Drive nine kilometres and turn right at the first fork, toward Hannah Lake. Another six kilometres will take you to another fork. Go left to reach the launch area or Mountain Cove Lodge.

Paddle the route counterclockwise, from Walker Lake to Bear, High, Basson, Panache and back to Walker. You can take a number of side trips from Bear Lake, allowing you to travel throughout the northern range of Killarney Provincial Park itself.

Info

Killarney Provincial Park: (705) 287-2900, ontarioparks.ca/english/kill.html

Friends of Killarney: (705) 287-2800, friendsofkillarneypark.ca

The route is written up in A Paddlers Guide to Killarney and the French River, by Kevin Callan, (Boston Mills Press/Firefly Books).

Outfitters

White Squall Paddling Centre: Nobel, Ontario, (705) 342-5324, whitesquall.com

Killarney Kanoes: Sudbury, 1-888-461-4446, killarneykanoes.com

Maps

Topographical maps: 41 I/3, 41 I/4.

Friends of Killarney will be coming out with an updated map marking campsites in the new area on July 1st.

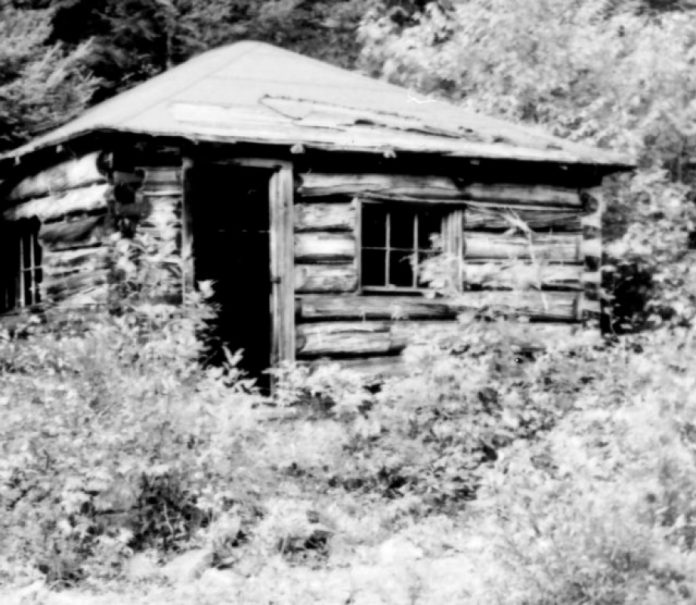

Probably didn’t know

Dan Brown and his sister Betty, both in their 70s, have lived reclusively on Panache Lake in a remote cabin all their lives. Their stories about the past are inexhaustible, including how a German spy, Baron von Hausen, sent radio signals to Germany from his cabin on Killarney’s Nellie Lake during the Second World War and how Al Capone visited the cabin of the ex-mayor of Chicago on Threenarrows Lake. Apparently enough tommy guns to sink a canoe were found behind the cabin’s walls when it was torn down.

Need to bring

Compass or GPS. The portage route gets a little confusing between Basson and Panache Lake and if you don’t take a bearing with your compass or GPS, you might find yourself wishing the route wasn’t so secret after all.

—Kevin Callan

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions