Things were looking promising for bear stories. As the highway took us past Kitwanga and approached the coast, as the mountains closed in and the Skeena river grew wide and flat for its home stretch, no fewer than five black bears, one after another, appeared grazing along the ditch.

Dave and I thought our paddle from Prince Rupert to Victoria would yield plenty of bear tales. It’s the great Bear rainforest after all. We came equipped with bear bangers, pen flares, and enough food-hanging ropes and hardware to climb a mountain.

Then the reality set in. Stroking past Princess Royal Island, home of that poster animal of the Central Coast, the Kermode or Spirit Bear—we saw nothing. The few times we set foot on mainland with our reflexes primed for an encounter with the griz—nothing. A gargantuan track here, a fresh mound of berry seeds there, some fearsome tooth marks in an institutional- sized mazola jug found eerily far inland from the shoreline junk pile—that was it.

I did once try to hang our food, the whole hundred-odd deadweight pounds of it, while Dave heartily mocked my efforts. And though our punching bag of produce hung laughably close to the ground, pooh stood us up on the piñata party. Probably the number two question we faced coming home after 80 days out besides Didn’t you get sick of each other? was Did you see a lot of bears?

Fact is, it’s in the margins of human civilization, where wildlife is crammed into the slender geography of wildlife corridors woven between golf courses, back alleys and garbage dumps— where wild omnivores are trapped between the privations of shrinking habitat and the temptations of human refuse—that is where you’re more likely to see bears.

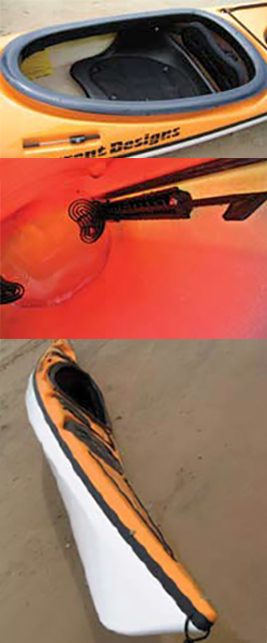

There are 46,000 square kilometres comprising B.C.’s Central Coast, all largely uninhabited, and the wild bears there have better things to do than entertain the few humans who arrive with mace in their pockets and bells on their packs. We learned that more than 99 times out of 100, leaving your food packed away neatly in your kayak hatch is the sensible and practical thing to do while you sleep soundly inside your nylon mesh panic room. And we learned that when you do see a bear in the wild, it’s something truly special.

We did, finally. It was late one drizzly day along a lonely Vancouver Island beach about six weeks in. she was a bumbling black hole in the fabric of the west Coast, flipping over rocks and cruising for something to eat. She never saw us. Or maybe she did. And that was all that happened.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions