No matter where you are reading this, you likely have a certain affection for the canoe. A recent trip to a U.S. event called Canoecopia helped me realize that the canoe is a much more populous and geographically-dispersed notion than some Canadians like to think. Unlikely as it might seem, there may be room in this realization for improvements in the social and political fortunes linking Canadians and Americans.

Canoecopia, organized by an outdoor retailer in Madison, Wisconsin, bills itself as the world’s largest paddlesports exposition. Largest, in this instance, means that in an exhibit hall the size of a small township hundreds of equipment manufacturers, boat builders, conservation groups, park personnel, paddling clubs, food vendors, gizmo inventers, and publishers (yes, Canoeroots was there) gathered to hobnob and hock their wares.

Add to that more than 7,000 canoeists (at least half of whom looked like Bill Mason, including a good proportion of the women) who sloshed in over three days in March. Besides the displays, these willing delegates could avail themselves of an Olympic-sized pool with dawn-to-dusk demonstrations and seven (count ‘em) theatres running simultaneous back-to-back programs every hour.

While navigating my way across the exhibit floor for the first time, the ever-perky Kevin Callan hied up out of nowhere and said, “Think of it as a Star Trek convention for canoeists.” That’s exactly what it was… a paddler’s mind meld.

I’d been invited to Canoecopia to speak about Bill Mason but by the time my presentations were done, I had attended programs about all aspects of the canoeing and kayaking world delivered by other people from near and far. And although I had crossed the border with a touch of trepidation (having been refused entry on a previous occasion), the sense of connection to these fellow paddlers, most of whom were American, highlighted a lesson and an opportunity.

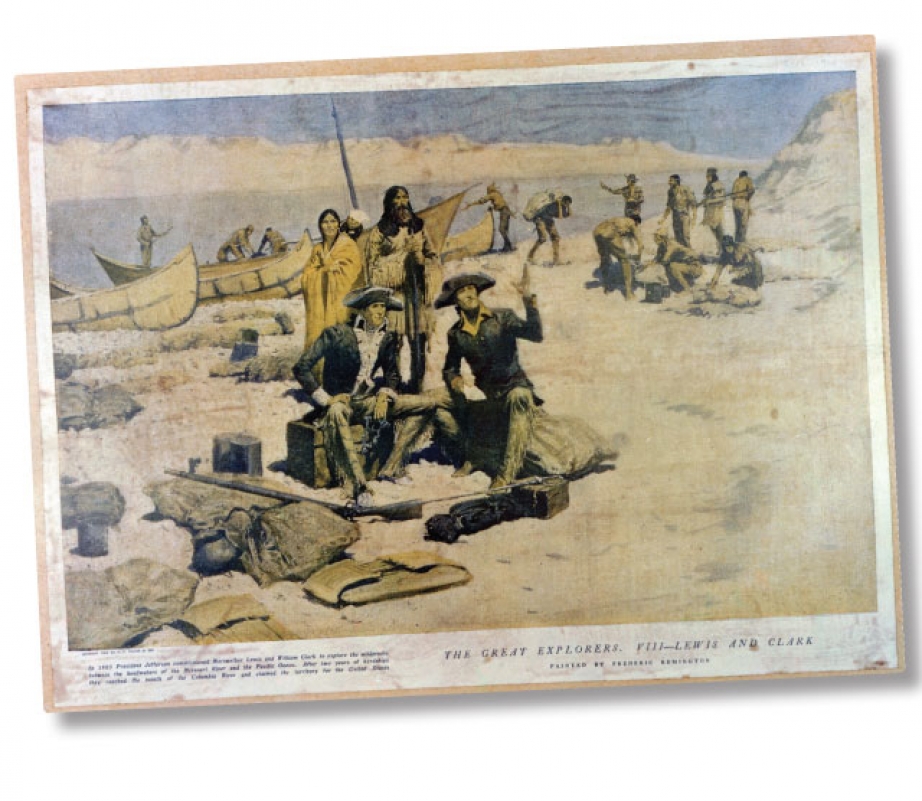

Although the canoe has a unique and special place in the hearts of Canadians, if one were to draw a line—let’s call it an isothwart—joining points of equal affection for the canoe, it would be clear that canoeophilia would not cease at the 49th parallel. You’ve got this enthusiastic rump of paddlers in Wisconsin and Minnesota. You’ve got Ralph Frese in Chicago (Uncle Sam’s Kirk Wipper…or is Kirk Wipper Canada’s Ralph Frese?) who argues that the American confederacy was not cast of horse shit and wagon grease, as so many believe, but of birchbark and pine pitch in the hands of French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, who crossed from Lake Michigan through to the Illinois River and down the Mississppi 434 years ago. You’ve got Lewis and Clark. You’ve got the great canoe building companies of the Northeast states. You’ve got boatbuilder Henry Rushton. You’ve got the Adirondack Museum and the Antique Boat Museum in Clayton, New York. You’ve got the American Canoe Association and the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association.

At a point in history when crossing the border is getting increasingly difficult, canoeists on both sides might consider showing leadership by working to celebrate what we have in common rather than capitulating to circumstances that would keep us apart. Rivers, fortunately, know no such bounds—the St. Croix, St. John, St. Lawrence, Red, Milk, Columbia, Fraser, Yukon and many more between—maybe it’s time we used them to paddle to meet our neighbours. As Henry David Thoreau once famously said, “Wherever there is a channel for water, there is a road for the canoe.”

James Raffan has not yet disclosed why he was once refused entry into the United States.