As I’m writing this I’m listening to my woodstove struggle against the cold of an Ottawa Valley winter. I’m also thinking of my canoe resting under a couple feet of snow on the edge of Jack’s Lake, just a short hike out my back door.

Jack’s Lake isn’t actually called that on any map. It’s too small to warrant a cartographer’s attention. It’s no different than thousands of others its size with names like Round, Mud, Clear or Stumpy—except on the south shore where the reeds aren’t as thick and there’s a gap in the cedars my old canoe is turned over, with two paddles underneath.

To say my canoe isn’t anything special would be being too kind. You might say it’s a piece of junk.

You can’t sell boats like my aged Old Town Discovery 169. I know this because the guy who gave it to me tried. Its resale value has been dragged out of it; you can see it on the rocks when the water is low. The bottom is cracked like salt flats, the deck plates have been torn off and the seats wiggle on rusted bolts.

As tired as it is, this canoe changes Jack’s Lake. Without my canoe you can only peek out from the water’s edge. With it, I know there are three beaver lodges and a dam on the southwest corner. I know that Jack’s is full of northern pike who take blue Rapalas just off the reeds. And I know that two loons nest in the same spot every spring.

I’ve never seen anyone else back there, but I know I’m not the only one who uses my canoe. A few years ago someone added a tangle of yellow anchor rope and a bleach bottle full of sand. And I’ve noticed different paddles have come and gone, but there are always two underneath it. Some paddles are longer, some are shorter; all are better than what I left there seven years ago.

There is a code about such things, a code that doesn’t need to be written down or posted on a sign.

I learned about the code on Swede Island, one of a chain of wilderness islands between Silver Islet and Rossport on the north shore of Lake Superior. The local sailing community has built an emergency shelter near a rickety pier extending into the protected harbour.

Paddlers and sailors use the shelter and scribble in a logbook, telling of their travels. They also chop more than their fair share of wood for the sauna and stock the shelves with stove fuel, silverware and cans of food. In guidebooks, Swede Island is an emergency shelter. It is a place left in the bush for others to use. It isn’t locked, nothing is ever stolen or vandalized. Swede Island is a place to learn about the unwritten code.

I like it there because everyone else likes it there also. And they do what they can to improve it—one can of chicken noodle soup at a time.

I’ll be moving soon but I’ll be leaving my old canoe under the cedars. I’m leaving it behind so that others can paddle with the loons in the spring, so that someone else can visit the beavers. Mostly, I’m leaving it there so that someday, when my son is old enough, we can walk back to Jack’s Lake to watch the sunset and cast blue Rapalas at northern pike.

When he asks me whose canoe it is and why someone just left it in the woods, I won’t tell him the truth; I won’t try to explain the unwritten code. I know he’ll figure it out someday when he finds his own Swede Island.

For now, I’ll just tell him the piece of junk canoe is just too damn heavy to carry home.

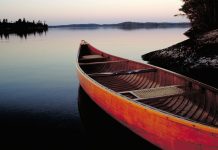

Left behind but not forgotten. Decades of stories etched into its hull. Feature Photo: Ontario Tourism

And in the “real” backwoods, folks don’t padlock their cabins either. They’ll secure them from animals, but they’ll leave a hammer or a screwdriver in the outhouse so a weary traveler can undo the door and take shelter for the night, leaving the next day after sweeping out and re-securing the door properly and, if possible, donating an addition to the basic supplies left in the kitchen for anyone who may need more than just shelter. Why do we have to get SO far away from “civilization” before we humans can be civil towards each-other?