From grassroots rodeo festival to slick mega-production, whitewater’s biggest competition has come a long way from a handful of river nomads gathering to twirl their paddles for bragging rights. With this year’s World Freestyle Kayak Championships expected to cost $425,000, and few whitewater companies ponying up cash to pick up the tab, has the long road to the Olympic dream created an event too big for the industry to support? Conor Mihell investigates.

It’s been over 20 years since boaters started getting together on rivers like the Ottawa, Caney Fork and the Ocoee, queuing up to surf waves and ride holes, throwing spins, enders and pirouettes instead of running downriver. Volunteer judges—often paddlers themselves—kept score; spectators by the hundreds crowded the rocky shores to watch. In the early days it was called rodeo and similar to its Western namesake, the events were spectacles, equal parts party and friendly competition to assert bragging rights on and off the river.

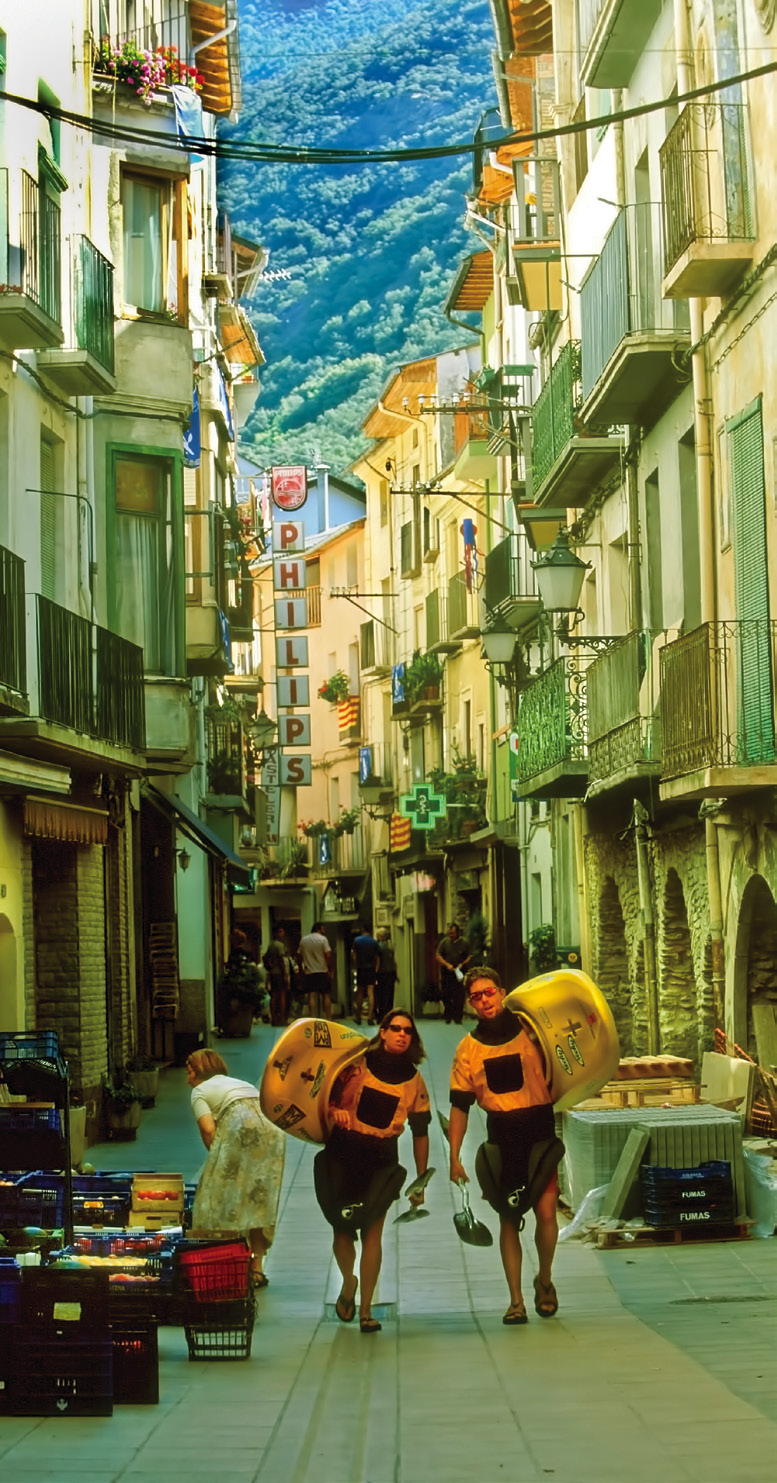

As with any upstart sport and competition, a faction of paddlers wanted whitewater rodeo to go bigger. The very first world championship was held in 1993 on the Ocoee River in Tennessee; in 1997, the worlds came to McCoy’s rapid on the Ottawa River; and by 2001, the event engulfed the Pyrenees village of Sort, Spain, in a boisterous festival. Over time, competitors morphed from weekend warrior types, raft guides and paddling school instructors to elite professional athletes with sponsors, including kayak brands, energy drinks and automobile manufacturers. It seemed as though freestyle, as it later became known, was destined for mainstream success—some even dreamed of inclusion in the Olympics.

Today, the Switzerland-based International Canoe Federation (ICF) sanctions the biannual World Freestyle Championships. The worlds is now an international event with choreographed routines, professional judging and live-streamed broadcasts. To perennial optimists like Eric Jackson, a long-time competitor and freestyle pioneer, the “media, pomp and circumstance” of ICF championships push the sport forward. “It’s about keeping the trend upwards,” he says.

Yet as much as world championships have showcased freestyle kayaking, industry sales figures haven’t kept up—in part, some believe, because the activity has become less relevant to the masses.

“It’s now a sport for elite athletes,” says Corran Addison, the founder of Riot Kayaks and a freestyle and slalom competitor in the 1990s. “Back when I was competing, this is exactly where I would’ve hoped freestyle would be. But now I’m not sure it’s a good thing. Freestyle has become like slalom. It’s not all that attractive to the average paddler.”

Decreasing sponsorship dollars and greater demands mean hosts of the big show can be seriously burdened by red ink.

Inspiring the next generation

This September, the ICF World Freestyle Championships return to the Ottawa River for the third time. Two-time event organizer Matt McGuire says the $425,000 festival at Garburator will be a far cry from the previous Ottawa worlds, held in 1997 and 2007 and run by volunteers on shoestring budgets.

McGuire hopes Garburator’s dynamic, heaving foam pile and the Ottawa’s remote, rocky shores will exude a siren’s call to competitors and spectators, and in turn captivate a new generation of whitewater enthusiasts. Compared to the 2013 worlds, held on a diminutive, man-made hole on North Carolina’s Nantahala River, athlete registration is up. Although costly, McGuire insists broadcasting real-time video footage of the world’s best paddlers competing in the Canadian wilderness has the potential to inspire people around the globe.

“Freestyle kayaking is a spectacular sport and the Ottawa River is a spectacular place,” he says. “Nowhere else has hosted the world championships twice, let alone three times. It is the best place in the world to have a freestyle event.”

Looking back

The whitewater industry blossomed in lockstep with the popularity of freestyle kayaking. Early world championships were as much a competition between boat manufacturers as paddlers.

“It was totally driven by the manufacturers,” recalls Joe Pulliam, the former president of Dagger Kayaks. “It was a battle between Wave Sport, Dagger and Perception. Teams were divided up according to brand of boats, not countries.”

There was big money to be made in producing a championship design because freestyle kayaks had not yet evolved into a separate genre, distinguished as they are today by their radical shapes and fragile composite construction, explains Pulliam. Boats like the Wave Sport X and Dagger RPM flowed out the doors of paddling shops into the hands of recreational paddlers. Athletes like Team Dagger’s Brad Ludden scored fully loaded Subarus (Wave Sport partnered with Chevy Trucks) and gas cards, with instructions to hit as many rodeos in the season as possible. In 2002, South African athlete Steve Fisher earned $25,000 from Riot Kayaks alone, according to Addison.

“About three-dozen athletes were making a real living off kayaking,” notes Addison. “The best guys pulled in $125,000 per year.” At the top of the game were Addison and Sean Baker.

Pulliam says the early rodeos were all about showmanship. Freestyle was viewed as counterculture— paddling’s version of snowboarding. Addison was known for his bad boy persona; EJ was the slalom Olympian-turned-freestyle jock. A repurposed limousine equipped with roof racks shuttled Perception boaters, while Team Riot arrived in a svelte black bus.

“You don’t see someone doing a big ender or pirouette, whooping and throwing their paddle away anymore,” laughs Pulliam. “The judging was subjective and it was all about crowd appeal.”

As long as you could ante up the $40 registration fee, which covered things like meals and camping, all competitions were open to everyday boaters.

“Some boaters were just there for the party,” notes Jackson, who has topped the field four times out of the 11 world championships in which he competed. “They became more out of place over the years. This is the world championship, not a hometown throw-down.”

And so a mixed bag of professional kayakers and local weekend warriors descended on the Ottawa for the 1997 worlds, which was won by Canadians Ken Whiting and Nicole Zaharko. Boat manufacturers and regional outfitters provided sponsorship in the form of raffle prizes, demos, workshops and camping.

“The interest in McCoy’s was overwhelming,” recalls Paul Sevcik, a member of the 1997 organizing committee and owner of Equinox Adventures, an outdoor skills school based in Toronto. “But we never made a penny. Everything was done with volunteer labor.”

But then things began to change

Addison points to the early 2000s as a turning point. World championships held in Spain in 2001 and Austria in 2003 boasted far bigger budgets and carnival-like atmospheres, at the expense of the grassroots feel. The paddlesports industry played less of a role in supporting the European competitions. As freestyle competition evolved, a gulf widened between athletes and enthusiasts.

“The average punter could no longer do the moves the athletes were doing. Shit, they couldn’t even identify them,” says Addison. “Meanwhile, the Steve Fishers of the world realized there was more money in hucking waterfalls in Iceland than flopping around in some little hole.”

A pivotal moment occurred in 2007 when the ICF began sanctioning world championship events, buoying a movement to make freestyle an Olympic sport and further influencing its trajectory. On the other hand, that year also brought competitors back to whitewater’s heartland. McGuire and Wilderness Tours, a rafting operator and kayak school in Foresters Falls, Ontario, hosted the worlds on the Ottawa River’s infamous Buseater wave, generating huge buzz amongst competitors that harkened back to the early days of rodeo.

McGuire says the Buseater event galvanized his vision of a freestyle event. “Athlete experience is paramount,” he says. “The wave needs to showcase the sport in a light that the athletes enjoy. It needs to make the competitors feel challenged, like the sport is going in the right direction. They come out in droves for a feature that’s world class. We saw this with Buseater. With the right feature, everything else falls into place.”

“It was a wilderness event,” recalls U.K.-based athlete Claire O’Hara, who made her world championships debut in 2007 and has since become a dominant force in women’s freestyle with two ICF world titles. “Buseater is a feature that most athletes would never otherwise experience.”

McGuire says hosting an event on the Ottawa River imposes a “steep rural tax” on organizers. Providing space for judges and spectators along a rocky shore, coordinating peak water levels with Ontario and Quebec hydro power utilities and finding banquet space in the backwoods of the Ottawa Valley all came at a cost (which McGuire refuses to disclose). In this sense, the 2007 worlds represented a transition to a new worlds economy.

The next installment, held in 2009 in Thun, Switzerland, upped the ante with “huge TV screens, big air ramps, festivals, live-streaming and massive spectator grandstands,” says O’Hara.

Things were progressing as Jackson hoped. “If an organizer wants to be a local, low-budget event, they should not bid for the world championships,” he says. “Athletes who want lower-key can find these events around the world all season long. The world championships is a stage set for the best freestyle kayakers in the world to compete and show off the sport.”

The Nantahala Outdoor Center invested $195,000 into an engineered hole for the 2013 worlds. While some athletes were disappointed in the feature, huge media and broadcasting efforts made it the most-watched worlds of all time. Now, McGuire admits Ottawa 2015 could be a last hurrah—perhaps “the last world championships on a naturally flowing river” because of the challenges of hosting an event in such a remote place.

“We’re not a canned venue,” he says. “We’re a remote, god-awful place to run an event. How do you get Internet to a place that doesn’t have power? How do you set up the proper facilities for the judges? How do you pack 1,000 people on a rocky shoreline that isn’t all that pleasant for a group of paddlers to sit and watch their buddies surf Garb?”

The answer: You spend a lot of money.

The green problem

Securing funding is a struggle for all whitewater festivals—freestyle, creek racing and otherwise. The financial travails of Patrick Camblin, organizer of the boundary-pushing Whitewater Grand Prix, included $80,000 of debt going into the 2014 event. This June, Idaho’s Payette River Games, whose $100,000 purse is the largest in paddling, dropped kayak events altogether in favor of standup paddleboarding.

“We have really enjoyed doing our best to promote and expand the sport of whitewater kayaking over the past four years through our competitions with record-setting purses,” said organizer Mark Pickard in a press release. “But we’ve decided not to underwrite the expense of hosting another kayak event.”

For host Wilderness Tours, the 2015 World Freestyle Kayak Championship is more about promoting the Ottawa River as a destination than turning a profit. Sponsors include Wilderness Tours’ partner Algonquin College, a local post-secondary institution with a renowned outdoor adventure program, energy giant TransCanada (which, incidentally, has plans to build a massive oil sands pipeline through the area), and Ontario Power Generation and Hydro-Quebec, whose support is more related to providing the appropriate water levels than injections of cold hard cash. At press time, apparel and accessory manufacturer NRS stands alone in representing the paddlesports industry amongst title sponsors.

“We think sponsoring the World Freestyle Championships is the right thing to do,” says NRS brand manager Mark Deming. “For us it’s about being a good citizen, number one, but the event organizers are doing a great job of making sure we realize a strong value from our investment.”

The brands and sponsors

Marketing philosophies are changing, explains Deming. Companies are moving away from traditional athlete and event sponsorship to web-based platforms. “The brands that go big into events”—such as GoPro, which made a last-minute contribution to the 2014 Whitewater Grand Prix and helped salvage Camblin’s bottom line—“are able to roll them into online campaigns where they’re basically creating content,” continues Deming. “That content is more important than the event itself.”

Jackson insists that the paddlesports industry shouldn’t be responsible for bankrolling world-class events. European hosts have employed freestyle’s television-friendly format to gain the support of brands like Volkswagen and Keen Footwear. Coca-Cola and Subaru contributed to the 2013 world championships in North Carolina, as well as Confluence Outdoor (which owns the Wave Sport, Dagger, Bomber Gear and Adventure Technology Paddles brands).

“The truly large-scale events, such as freestyle world championships and the Whitewater Grand Prix, really need much larger sponsors to help them flourish,” says LiquidLogic Kayaks designer Shane Benedict. “The events that support local rivers, clubs and are more connected with the core of the sport are more our focus.”

This means organizers like McGuire are forced to court big business— another hurdle for rural events.

“The level of [financial] commitment that it takes to have a meaningful impact on an event like this is beyond the threshold of most businesses in paddlesports,” says Deming. “If you look at the sponsors of the past two worlds—Confluence at Nantahala and NRS on the Ottawa—we’re probably the two biggest companies in paddlesports. The writing’s on the wall.”

Barriers… but not insurmountable ones

Whitewater kayaking is different from surfing or skiing in that the most appealing places to paddle are out of the way, far removed from beaches, resorts and urban areas. By dint of geography alone, whitewater can never be as popular as mountain biking and standup paddling. Some paddling evangelists believe urban whitewater parks are freestyle’s future. But the reality is, electrifying features like Garburator and Buseater only exist in the wild. As infrastructure demands for freestyle events grow, hosting them at the places that best define whitewater becomes more and more improbable.

Yet competitors are hopeful. As much as the British freestyle phenom raves about the Ottawa, O’Hara’s eyes are locked on the future. The 2017 worlds have been awarded to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and will take place at the newly constructed Olympic whitewater facility. Sort, Spain, will host the 2019 freestyle event alongside wildwater and slalom world championships.

“Then who knows, we could potentially see an adventure community river-based event on a feature such as the Hawea Waves in New Zealand,” says O’Hara. “At which point we could very well be an Olympic sport.”

Meanwhile, McGuire is betting on Garburator’s wild aesthetics. “Back in ’07, there was an energy in the room during the awards ceremony that was insane,” he says. “I’ve never experienced anything like it before. It was a small room with 600 people jammed in, and we’d just finished the first world championships on a wave that wasn’t four feet high. We were on the Ottawa with this tight-knit community.

“I’m a boater,” he continues. “I love the sport and I love the Ottawa River and I would do anything for the river and the people who surround me on the river. That’s why I know we’ll succeed.”

A brief history of the World Freestyle Kayak Championships

A brief history of the World Freestyle Kayak Championships

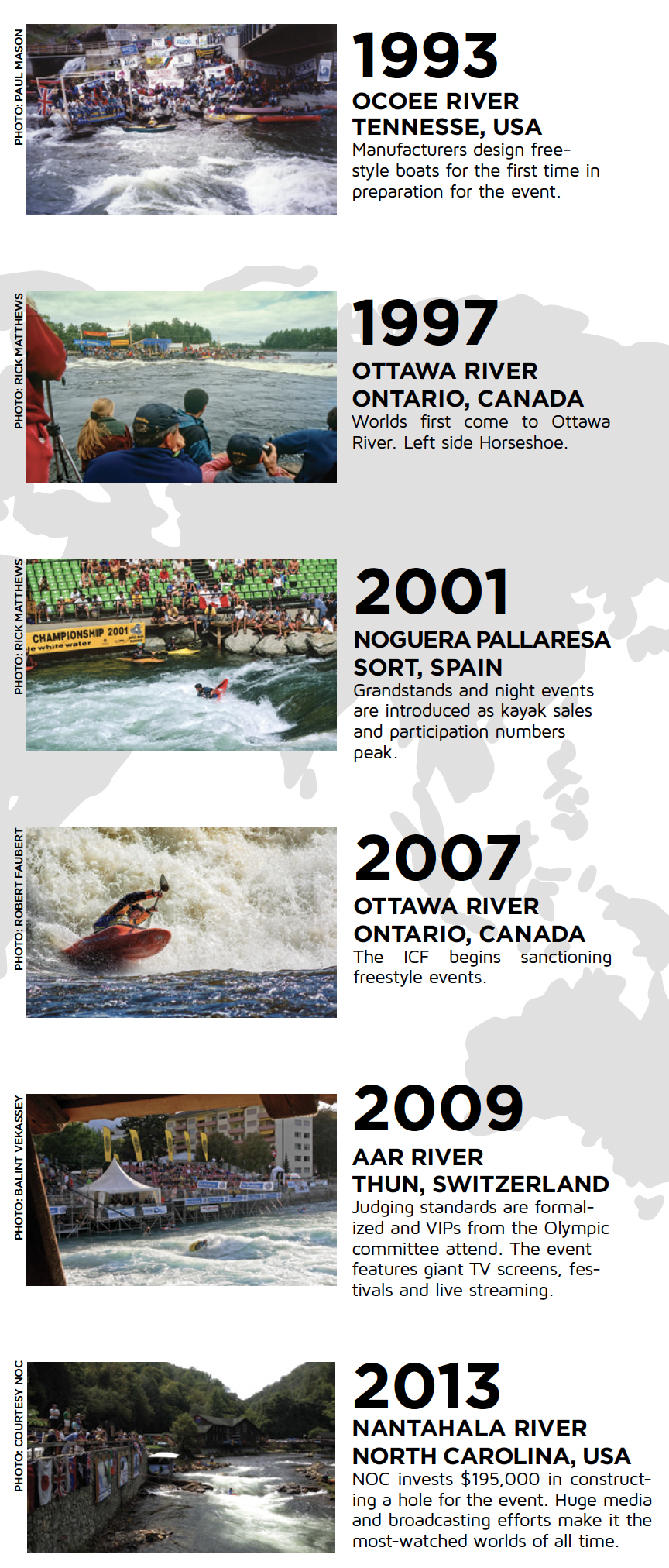

1993: Ocoee River – Tennesse, USA

Manufacturers design freestyle boats for the first time in preperation for the event.

1997: Ottawa River – Ontario, Canada

Worlds first come to Ottawa river.

2001: Noguera Pallaresa – Sort, Spain

Grandstands and night events are introduced as kayak sales and participation numbers peak.

2007: Ottawa River – Ontario, Canada

The ICF begins sanctioning freestyle events.

2009: Aar River – Thun, Switzerland

Judging standards are formalized and VIPs from the Olympic committee attend. The event features giant TV screens, festivals and live streaming.

2013: Nantahala River – North Carolina, USA

NOC invests $195,000 in constructing a hole for the event. Huge media and broadcasting effects make it the most-watched worlds of all time.

Conor Mihell is a freelance environmental reporter and adventure journalist. Find him at conormihell.com.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Rapid Magazine.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

A brief history of the World Freestyle Kayak Championships

A brief history of the World Freestyle Kayak Championships