I’m somewhere above the top of the world, the place where trees are a distant memory and you become convinced there are a thousand shades of white. Snow and ice and wind and a couple of hundred Canadian Forces members, scattered in and around Alert, the most northern military base in Canada. It’s the spring of 2010, and Arctic sovereignty has been the buzzword of the decade. As a freelance photographer and writer, I’ve been assigned to showcase Canada’s efforts in a land where people don’t normally live.

A couple of days into this story, there’s a second story brewing. Word spreads quickly through the outpost: an Australian adventurer has put out a distress signal 50 days into his attempt to trek solo and unsupported to the geographic North Pole. A rescue team from the Canadian Forces is dispatched. It’s coincidence, and extremely good fortune for the troubled Australian, that the team is currently here at Alert for the operations that I’ve been assigned to cover—normally they are stationed thousands of kilometers to the south. The rescue is pulled off without a hitch and the Australian is brought back to the base.

This is how I meet Tom Smitheringale, a six-foot-seven-inch, 260-pound giant with a broad smile, month-long beard, slight limp and the appetite of a bear having awoken from hibernation. An hour later I’m photographing him, stripped to his skivvies in a base washroom, documenting a moderate-to-severe case of frostbite that has blackened the ends of his fingers and toes. All I can think is, “Shit, did he really just fall into the Arctic Ocean, halfway to the North Pole…and survive? And he’s got the strength to smile?”

Fast-forward 18 months. I’m bombing down a deserted highway in post-Revolution Egypt with three locals that I’ve just met earlier that day: our destination is the shores of Lake Nasser near the Sudanese border to the south. Our tiny car has almost sunk to its axles from the weight of the gear we carry, and every bump feels like someone taking steel-toed boots to my ass.

We stop to stretch our legs at an ancient temple that looks long abandoned—a splendor rising from the sand. It’s the sort of thing that would be a major tourist draw anywhere else in the world. Here, a lazy dog is the only visitor. He raises an eye as we get out of our car.

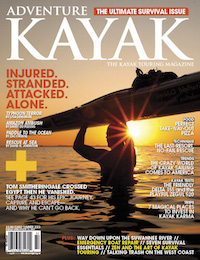

Down a nearby dusty track through the rock and sand, the shores of Lake Nasser finally come into sight. As does the silhouette against the sun of a giant, standing on the deck of a decrepit barge, waving to us as we approach.

WHY EGYPT?

Eventually titled by his support team as One Man Epic: Mission Sahara, Smitheringale’s sophomore expedition was no small feat on paper: cross the bulk of Egypt under human power, starting with a five-day paddle down 550-kilometer-long Lake Nasser, one of the world’s largest man-made lakes (created with the construction of the Aswan Dam across the Nile about 40 years prior), in some of the hottest conditions imaginable. From Aswan he would continue a further 20-or-so days and an additional 1,250 kilometers down the historic Nile to the Great Pyramids near the capital city of Cairo.

After becoming the first person to kayak the entire length of the Egyptian Nile, Smitheringale planned to meet up with a Bed- ouin guide and a small team of camels in the historic city of Luxor. From there, he would set out into the Sahara’s Western Desert to cross some 1,300 kilometers to the tiny, ancient Siwa Oasis near the Libyan border.

Why Egypt? I wondered when Smitheringale confided in me his plans.

“It doesn’t take a great leap of logic to understand when you’re freezing your bits off in the Arctic, you want to go thaw out some- where hot,” he explained. Still he admitted, “Of all the insane ideas in the world, I acknowledge that crossing the Sahara alone with four camels, in a world beyond guidebooks, with no support sys- tem, no hope of rescue, armed with $20,000 in cash and a small pack of essentials has to qualify as instantly certifiable.“

INTRIGUE, ADVENTURE, AND DANGER

It all started smoothly enough. When I arrived, Smitheringale was just one day into his kayaking stage, and after the endless months of preparation, he was elated to finally be on the water. On Lake Nasser’s still surface, his Epic 18X Expedition—a highly efficient, race-inspired sea kayak that was manufactured in China and then shipped to Egypt—“cut through the water like the singing blade of a sharp knife.”

I followed this first leg of the Australian’s journey from the relative safety and comfort of a barge that the ever-fickle Egyptian government demanded tail Smitheringale as his official escort. According to the au- thorities, threats from crocodiles and bandits were too great to travel alone.

While accounts of Lake Nasser’s crocodile-infested waters proved greatly exaggerated—we saw just two small crocs all week—the danger of lawlessness was frightfully real.

Passing through some wild country on the Nile, traveling ahead of his escort, Smitheringale spotted “a crew of tough customers holding their AK-47s like cricket bats.” Waving hello,“I got a couple of ounces of lead in response,” he remembers. “Fearing the scene could go sour mighty quick, I made evasive maneuvers and put the kayak into cover.” Hoping his armed police escort would arrest the thugs, Smitheringale instead watched as his protectors fled downriver. Despite the government decree that he only kayak with his escort,“for more than half the trip, they never turned up or I succeeded in giving them the slip.”

Undeterred, he carried onwards. The three-and-a-half weeks Smitheringale spent on the Nile had its challenges but the rewards were many, too. The famous river was an object of constantly shifting beauty and intrigue, with something different to observe around every bend. Adventure travel is almost unheard of in Egypt, and it drew the curiosity of many along the route. “Some ran away screaming, but most people I met were downright chatty, hospitable, gracious and tons of fun,” he says.

After 31 days in “murder hot” conditions, Smitheringale completed the 1,800 kilometers from Lake Nasser to Cairo. Another 75 days and he had finished the 1,300-kilometer crossing of the Egyptian Sahara—a brutal slog with unpredictable beasts in a landscape favoring migraines and mirages.

That should be the end of this story. But simply doing what he set out to do was not enough for Smitheringale; he made a decision that would take his trip into a world of intrigue, adventure and danger seemingly scripted for Hollywood.

SOLITARY CONFINEMENT IN LIBYA

Perhaps it was one too many days in the sun; perhaps it was just the notion of doing something even grander. Smitheringale decided he wasn’t done in Siwa. He wanted more. And more, in this case, meant crossing into Libya with the intent of traversing all of the Sahara in North Africa right through to Morocco. This, shortly after Libya made headlines the world over with the hunt for deposed despot, Muammar Gaddafi. It was, Smitheringale would later admit,“The single most stupid move of my life.”

Eight days after crossing into Libya, he arrived in the border town of Al-Jaghbub, fell out of communication with his support team, and was accused of having a false passport and being a spy by trigger-happy militia. Arrested “at the business end of an AK-47” he was thrown into solitary confinement at a Libyan militia prison for 28 days.

As days stretched into weeks, his supporters held their breath. Finally, word came in the form of a Facebook post from Smitheringale on March 7, 2012, stating that he had been released, but with few other details. The post read, “It would be inappropriate of me to elaborate on the details of my capture and extraction as I’m still in country.”

What the world didn’t know—and it has never been published until now—was that a British Special Operations Team extracted Smitheringale and relocated him to a safe house where he spent the next four days being debriefed by a number of different agencies working in the country. Liberated in the most dramatic of manners, he was to return home on the “advice of British authorities.” The expedition was over.

SETTLING DOWN

Smitheringale is now back in Australia working, perhaps appropriately, as a consultant for an operational risk company. For now, he is taking a break from the world of swashbuckling adventurer. “Time will decide [what’s next]. I’d like to fall in love, get married and have kids,” he confided in a recent conversation. Never one to seek the spotlight, he seems content to slip back into anonymity. I believe Smitheringale is genuine about settling down. But then again, as he says, “ The true test is not in the talking but in the doing.” Time, after all, may reveal something grander.

Dave Brosha is a photographer, author and filmmaker based in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, where he lives with his wife and three young children.