Anyone who has ever undertaken a restoration project knows one of the curious features of canoes is that when you bisect the craft, amidships and from stem to stern, the quarters you’re left with are not identical replicas of one another.

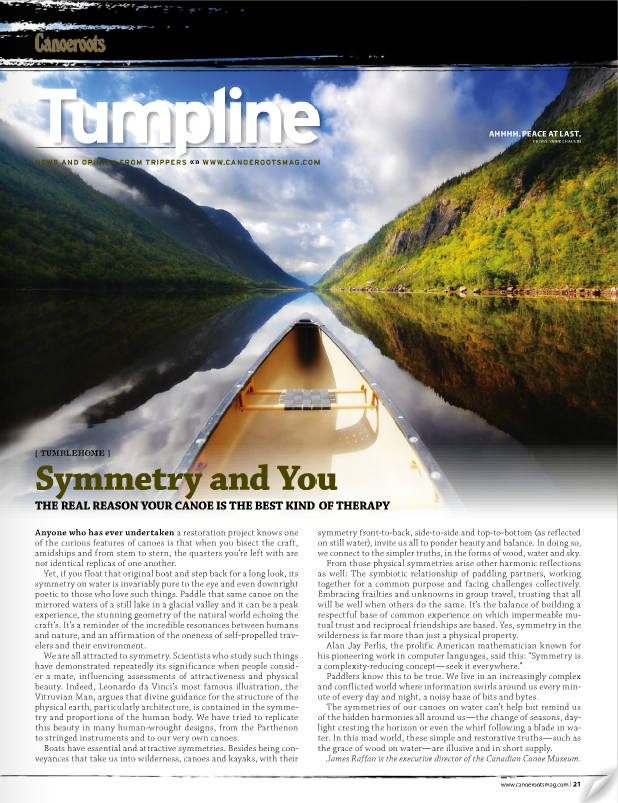

Yet, if you float that original boat and step back for a long look, its symmetry on water is invariably pure to the eye and even downright poetic to those who love such things. Paddle that same canoe on the mirrored waters of a still lake in a glacial valley and it can be a peak experience, the stunning geometry of the natural world echoing the craft’s. It’s a reminder of the incredible resonances between humans and nature, and an affirmation of the oneness of self-propelled travelers and their environment.

We are all attracted to symmetry. Scientists who study such things have demonstrated repeatedly its significance when people consider a mate, influencing assessments of attractiveness and physical beauty. Indeed, Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous illustration, the Vitruvian Man, argues that divine guidance for the structure of the physical earth, particularly architecture, is contained in the symmetry and proportions of the human body. We have tried to replicate this beauty in many human-wrought designs, from the Parthenon to stringed instruments and to our very own canoes.

Boats have essential and attractive symmetries. Besides being conveyances that take us into wilderness, canoes and kayaks, with their symmetry front-to-back, side-to-side and top-to-bottom (as reflected on still water), invite us all to ponder beauty and balance. In doing so, we connect to the simpler truths, in the forms of wood, water and sky.

From those physical symmetries arise other harmonic reflections as well: The symbiotic relationship of paddling partners, working together for a common purpose and facing challenges collectively. Embracing frailties and unknowns in group travel, trusting that all will be well when others do the same. It’s the balance of building a respectful base of common experience on which impermeable mutual trust and reciprocal friendships are based. Yes, symmetry in the wilderness is far more than just a physical property.

Alan Jay Perlis, the prolific American mathematician known for his pioneering work in computer languages, said this: “Symmetry is a complexity-reducing concept—seek it everywhere.”

Paddlers know this to be true. We live in an increasingly complex and conflicted world where information swirls around us every minute of every day and night, a noisy haze of bits and bytes.

The symmetries of our canoes on water can’t help but remind us of the hidden harmonies all around us—the change of seasons, daylight cresting the horizon or even the whirl following a blade in water. In this mad world, these simple and restorative truths—such as the grace of wood on water—are illusive and in short supply.