After a month of non-stop paddling in southern Siberia, my friends Don, Darcy and I decided to head back to the Chuya River for our last three days. It was a river that had humbled us just weeks before and we knew it would be an exciting way to finish our adventure in this sparsely populated corner of northern Asia.

On our last evening, Darcy and I were sitting by the river at camp, reflecting on a remarkable trip that we both agreed was a highlight of our paddling careers. Nevertheless, after a month of non-stop Class V Siberian whitewater, my nerves were shot and I was looking forward to returning home.

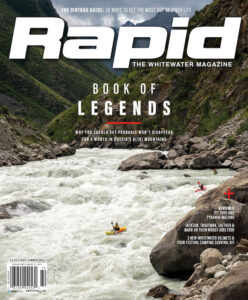

Triumph and tragedy in Russia’s Altai Mountains

As we sat there in the last light of day just downstream of Mazhoy Gorge where our trip began with wide eyes at the incredibly deceptively-named Baby Rapid, Darcy spotted something floating in the river. “Looks like a helmet,” she said with concern. As the object came nearer, it suddenly hit us what we were witnessing. “A body! There is a body floating in the river!” Darcy yelled to get the attention of anyone in proximity. And there, in the last moments of our trip we watched as a drowned catarafter—one of two, we later learned—floated slowly past us.

It was a sight that shook Darcy, Don and I to the core and one all too familiar to the local Russian paddlers, cementing what we had come to learn during our time in the Altai; the whitewater community in Siberia is a world away from the one we know.

Early one spring morning I opened an email from my good friend Darcy Gaechter. She wrote asking if I was interested in joining her and her partner Don Beveridge on a paddling trip to Russia’s Altai Mountains.

“Darn, this is a tough call,” I typed back. The Altai had long been at the top of the list of places I wanted to kayak, but I wasn’t sure if I was fit enough. I had met Darcy and Don years earlier in Ecuador, where they run Small World Adventures, a kayak guiding firm on the Quijos River. The pair are no strangers to big adventures, having previously paddled the Amazon from source to sea.

After much back and forth I realized that this was too good an opportunity to pass up—to journey with experienced and trustworthy paddling partners to the Siberian wilderness. I just couldn’t say no.

To make the trip possible we joined Two Blades Adventures, a company run by Egor Voskoboynikov of Russia, Alona Buslaieva of Ukraine and Tomass Marnics of Latvia. They offer logistics and guiding to some of Russia and Central Asia’s finest paddling destinations, including the Altai, the heart of Siberian whitewater. Without them, there was no hope in overcoming the language barrier and navigating the complex logistics including remote put-ins and takeouts, bad roads and corrupt officials.

The Altai Mountains are located in southern Siberia, where Russia, Mongolia, China and Kazakhstan converge. Here the thick pine forest of Siberia meets the high altitude Mongolian steppe and the steep mountains of the ‘Stans. This unique geography makes for a rich culture and history. Statues of Genghis Khan are scattered throughout the region highlighting the Mongol influence. Ruins of failed industrial projects are a reminder of the Soviet planned economy and tough, shirtless and outdoor-loving Russian men perfectly symbolize the country’s newfound ambition in the world today.

Arriving in Novosibirsk, located in southern Siberia and the closest major airport to the Altai, it was another two-day drive to the mountains. The drive on neglected highways followed the Ob River—the main watershed draining the Altai and one of the world’s longest rivers.

Meeting Egor at the airport was my first glimpse of what Russian paddlers look like. If there were a comic book kayak character, he would look like Egor. He is six-foot-two, with a slim waist, barrel chest and shoulders like a bear. My first question after my much-practiced “privet”—hello in Russian—was what the water levels were like.

“We had lots of snow and it’s been raining every day for a month,” was Egor’s terse response. This was a Russian of few words.

Siberia is known for huge water in normal years, so I wasn’t hoping for high water. I didn’t relax much during the drive.

Getting humbled on the Chuya

After warming up on a few easier rivers on the two-day drive to the mountains, the first real stop was the Chuya River. The Chuya is the focal point of the Altai paddling scene, in part because it is a main transit corridor for trade with bordering countries, which makes access and logistics easy, but mostly because it offers incredible whitewater. There are several different sections to paddle on the Chuya River, but the Mazhoy Gorge is the undisputed king.

After hearing many tales of fast and continuous whitewater interspersed with steep and technical big-water rapids, the Mazhoy Gorge seemed like too big a first test to Darcy, Don and I, especially at high water. Instead of running the section from the top, Egor suggested we hike into the end of the canyon to run the last few easier rapids of the gorge, from Baby down to the Class IV rafting section below.

After that first introduction to the raw power of Russian whitewater, we decided to go for a full run of the Mazhoy the following day. The Mazhoy started off with an hour of continuous Class IV-V wave-trains, interspersed with big crashing holes and sharp corners. We scouted a few times, but mostly followed Egor’s concise and very accurate descriptions and stayed closed on his stern. As the run progressed, the canyon tightened and the rapids grew steeper and more defined. The last eight kilometers offered back-to-back Class V rapids that had tight lines past giant holes and essentially flowed one into the next. The Mazhoy’s continuous glacial water reminds me of British Columbia’s Soo River, but the size of the rapids approach those of the mighty Stikine.

This last section in the Mazhoy Canyon is also the location of the annual King of Asia Extreme Race. We were there during the event, but none of us had the courage to race down a section we were simply relieved to reach the bottom of. We happily used the excuse that we had many of the Altai’s other great rivers to explore and left Egor and Alona to try and defend their King and Queen of Asia crowns.

The King of Asia race has two distinct events. The first is a half-mile head-to-head race with a seal launch start off an old wooden bridge right into a big hole. The main event is a downriver race on the Mazhoy where racers sprint for 10 minutes before charging into the final and biggest rapid, Russian Hills, which starts with a must-make boof over a huge hole and then drops 40 feet through several more large hydraulics. The mostly Russian competitors celebrate survival with a wild vodka-fueled party.

Being able to hold a race on a run as difficult and remote as the Mazhoy is a testament to the vibrancy of the Russian paddling community. Not only is there a large and tight-knit group of passionate river people in Russia, they are also incredible paddlers. In comparison to us recreationists in the West, Russian paddlers are real athletes—they train with Olympic discipline and possess steadfast mental strength, no doubt linked to the important role that sports play in Russian society. Combine this with a strong slalom background for many of the local paddlers— a legacy from the Soviet Union—and you get paddlers the caliber of our guide, Egor.

The Bashkaus—Paddling through Russian river running history

Equally telling of the Russian dedication to river running is the country’s rich history of exploring Siberia’s rivers dating back to the Soviet days. In the 1960s and 70s, adventurous Russianswould request permits for accessing remote rivers with the official purpose of helping map the vast Siberian hinterland, but which in reality was for nothing more than the personal enjoyment of river running.

Lacking proper equipment, these adventurous Russians would build makeshift rafts, often constructed at the put in by cutting down trees and tying them to truck innertubes or old germ warfare suits for flotation. The rafts typically came in two styles: the classic Russian cataraft and the infamous Bublick—in which two innertubes are tied together with trees so that the tubes stand vertical with paddlers strapping themselves inside.

Having assembled their makeshift crafts, brave young men and women would then attempt Siberia’s most remote and challenging rivers. Many river runners paid the ultimate price, a fact that only increases the mystique around paddling in Russia. On many of Siberia’s rivers, commemorative plaques are erected remembering friends who never made it back on dry land.

This adventurous spirit lives on today in the local catarafting community. These craft look modern enough. But the catarafters’ equipment, including old hockey helmets, empty plastic water bottles taped to metal paddles for floatation, and giant full-body lifejackets make the rafters look like cosmonauts. Yet this outdated equipment doesn’t stop large numbers of Russians from braving the country’s most dangerous rivers.

No river has a richer and more dramatic history than the Book of Legends section of the Bashkaus. Widely considered the most challenging multi-day run in the Altai, this stretch of river is revered as much as feared in Russian river running lore.

During the first descent attempt in the mid-70s, multiple people, including expedition leader Igor Bazilevsky, drowned in one of the first major rapids, bringing the expedition to a tragic end. Today, a commemorative plaque marks the spot, accompanied by a rusty metal box. Inside this box lives a logbook called the Book of Legends, whose pages have been signed by all groups attempting the run since 1978.

I was nervous paddling into this section, having only heard rumors and tales of 212 named rapids amidst a remote and at times inescapable canyon that has seen more than 30 fatalities since the first descent. I felt confident knowing that I had trained hard for this trip, yet I knew even British Columbia’s notoriously steep and powerful rivers couldn’t have prepared me. Day one was mostly a warm-up. At camp I slept poorly, with vivid dreams of what lay downstream.

The next morning we packed camp and slid into the water just as the fog from the previous night’s rain was lifting. The first rapids were dangerous with sticky holes in the main flow and siphons on the side, causing us to portage several times. A little further downstream we arrived at the run’s namesake rapid and the site that ended the first descent attempt in disaster. Only Egor was brave enough to attempt this maelstrom. He fought to make the line and made it to the end without flipping.

Once safely at the bottom of this rapid, we climbed up the canyon wall and found the memorial and below it, the Book of Legends. We spent half an hour carefully turning the pages, captivated by epic narratives from earlier expeditions and then humbly scrawled our own names in the historic book.

My energy soared after this and I began to appreciate the murky green water, polished white boulders and near vertical canyon of the Bashkaus. After eight hours we finally arrived at the take-out, high-fived and hugged each other, ecstatic that we had just safely run one of the most challenging and dangerous rivers we would ever attempt.

Travelling through vast landscapes on the Argut

Next we headed to explore the Karagem and Argut Rivers. The journey to the put-in required an all day off-roading mission along the Mongollike steppe, through creeks and over mountain passes often without any semblance of a road or track. This would have been impossible were it not for our trusted UAZ 452, a Soviet era off-road van. The inside of the van had nothing more than sheet metal and a hard bench, a bare bone set-up that proved advantageous when water would rush into the cabin in one of several river crossings.

Once we could drive no further, we shouldered our boats, laden with gear and food for four days and started walking down an overgrown track. After three hours we arrived at the bottom of the valley. We were greeted by two glacial creeks merging and a sub-alpine meadow filled with purple wildflowers in full bloom. Glaciers hung off jagged peaks above an abandoned hunting cabin. Home for the night.

The next morning we started on the Karagem, a fast and steep glacial creek. After 40 kilometers and dropping more than 1,000 meters in elevation we joined the much bigger Argut. On the Argut we rode 100 kilometers of Class IV-V wave trains that left the Mongol Highlands behind and quickly approached the jagged mountains of the Siberia-Kazakh border.

After our last three days on the Chuya it was time to start the long journey home. Driving away from the river on our last morning, my mind wandered back to how our trip had started with wide eyes at Baby Rapid. “If that was Baby, what does the rest of the trip hold in store?” I had nervously asked Darcy at the bottom of that rapid, trying to catch my breath after being swallowed in the surging hydraulic. A month later I had the answer.

We had paddled eight new rivers—including three multi-day runs—descending hundreds of kilometers of whitewater. We had seen rare animals and slept at beautiful campsites. But it hadn’t all been easy. I was intimidated for much of the trip, which slowly wore me down mentally. We had gone hungry, endured bad weather and witnessed stark tragedy. Driving away from the Chuya, I couldn’t help but smile. All the apprehension and hardship had been worth it. I had forever etched my name into the Book of Legends.

Maxi Kniewasser is a conflicted individual. As a result, you can sometimes find him in exotic locations, but much more often on local Whistler runs like the Cheakamus, Callaghan and Ashlu.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Early Summer 2017 issue.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Early Summer 2017 issue.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.