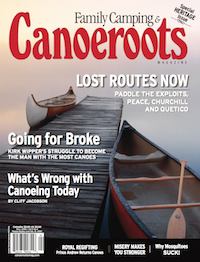

Cars have come a long way since the Model-T, modern bicycles bear little resemblance to penny farthings and the wright brothers would scarcely recognize a stealth bomber as an airplane. Despite a much longer history, the simple design of a canoe has changed little over the centuries.

maybe that’s why it’s easy to feel you are part of a heritage that is still very much intact whenever you push off from shore in a canoe. here are four routes on which it’s easy to commune with canoeing’s past.

Paddle in the spirit of newfoundland’s first inhabitants on the exploits, behind one of Canada’s greatest explorers on the Peace river, in tune with the voyageurs through Quetico and in the slipstream of those who helped rejuvenate canoeing as a recreational pastime on the Churchill River.

Peace River / British Columbia and Alberta

When Alexander Mackenzie paddled the Peace River in 1793, he described its shores as having “the most beautiful scenery [he] had ever beheld.” These are not words to be taken lightly coming from the explorer who criss-crossed Canada by canoe several times while seeking canoe routes to the Arctic and Pacific oceans.

Mackenzie was the first European to paddle the 2,000-kilometre Peace River. His crew of six wintered in Fort Fork, near the present-day town of Peace River, before continuing upstream against the Peace’s steady current in a reinforced, 25-foot birchbark canoe. When they ran out of river they portaged 14 kilometres over the Rockies and pushed on to the Pacific tidewater near Bella Coola, British Columbia.

In 1968, the W.A.C. Bennett Dam created Williston Lake—the largest in British Columbia—and manhandled the upper portion of the river. But below Hudson’s Hope the Peace River remains much the same as when Mackenzie paddled it more than two centuries ago.

Between Hudson’s Hope and the Alberta border the Peace is a prairie river, cutting a wind- ing course through 270-metre-high banks of silt and clay, its flow augmented by hundreds of ice-cold, mineral-rich springs. Mackenzie called this section of river “a magnificent theatre of nature [that] has all the decoration which the trees and animals of the country can afford it.”

To rediscover Mackenzie’s Peace River, put in at Hudson’s Hope, British Columbia, on Highway 29, and float just over 200 kilometres downstream and across the provincial border to Dunvegan, Alberta, on Highway 2. As long as you can handle easy whitewater, this section of river is portage-free and takes five to seven days to paddle comfortably.

Exploits River / Newfoundland

The Exploits River was once the main transportation artery for Newfoundland’s Beothuk. Like most aboriginal bands, the Beothuk were often on the move. They paddled 14- to 20-foot birchbark canoes up and down a 120-kilometre stretch of the Exploits to travel from their winter homes around Red Indian Lake in Newfoundland’s wildlife-rich interior to the Atlantic coast of Notre Dame Bay, where they spent their summers fishing.

But the Beothuk were more reclusive than other aboriginal bands when it came to dealing with Europeans. Rather than trading directly, they picked up discarded metal goods at abandoned European settlements, and altered their traditional routes to avoid encounters. Misunderstandings led to violent conflicts and their population plummeted. The last known Beothuk, named Shanawdithit, was captured in 1828. She died in St. John’s in 1829.

In addition to the attributes that made it appealing to its first paddlers—ample wildlife and a direct route from the interior to the coast—the Exploits makes for good day- and multi-day tripping for paddlers comfortable paddling in or portaging around class I to III whitewater. The Exploits holds its water well throughout the summer and parts of it see less traffic today than they did in the time of the Beothuk.

The best paddling on the Exploits is upstream of the Abitibi pulp mill in Grand Falls-Windsor. Beothuk Park, located in town on the Trans-Canada Highway, makes a good take-out. For a day trip, shuttle 20 kilometres upstream to Aspen Brook. Put in further upstream at Badger for an overnight trip or at Buchans for a four-day trip.

Churchill River / Saskatchewan

The revival of wilderness canoeing in the 1970s can be credited in part to a man who had remote waterways all to himself in the previous decades. Sigurd Olson, an environmentalist and writer from Minnesota, popularized recreational wilderness paddling with his accounts of canoeing in the Boundary Waters and Quetico area in his best-selling compilations of short stories, The Singing Wilderness and The Listening Point.

In these books, Olson eloquently described the charms and hardships of travelling by paddle and portage and living outdoors. But only one of Olson’s canoe trips was worthy of being the focus of an entire book—northern Saskatchewan’s Churchill River, which he described in The Lonely Land.

In the summer of 1955, Olson and five paddling partners—including Eric Morse, a University of Toronto historian and member of the band of canoeists dubbed the latter- day Voyageurs—paddled three cedar canvas canoes 800 kilometres down the Churchill and Sturgeon-Weir rivers from Ile-a-la-Crosse, Saskatchewan, to The Pas, Manitoba. It was unheard of at the time to take a seven- week canoe trip for pleasure.

“We traveled as the voyageurs did, paddled the same lakes, ran the same rapids, and packed over their ancient portages,” wrote Olson of their trip. “We knew the winds and storms, saw the same skylines, and felt the awe and wonderment that was theirs.”

The Churchill consists of a series of lakes connected by short channels of fast water. The main access points are Ile-a-la-Crosse, Missinipe and Sandy Bay, all of which are north of La Ronge, Saskatchewan. If you don’t have three weeks to paddle the 386- kilometre, 20-portage section between Ile-a-la-Crosse and Missinipe or two weeks to paddle the 222 kilometres between Mis- sinipe and Sandy Bay, your best bet is to fly in to a lake somewhere along the way. A great five- to seven-day trip involves chartering a floatplane from Missinipe to Sandfly Lake and paddling the Churchill’s network of lakes back to your vehicle.

Quetico / Ontario

Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park was once part of a voyageur route that stretched from Montreal to the furry heart of Canada.

Canoe brigades met in early July just east of Quetico at Fort William, near present day Thunder Bay, where the 36-foot birchbark canots du maitre from Montreal would exchange their metalware and muskets for the winter’s worth of pelts arriving from inland via smaller canots du nord. Once the last cask of rum ran dry, the canots du maitre would return to Montreal to send English gentlemen their sought-after beaver hats and the inland voyageurs would return to their posts.

Shortly after hauling their newly-acquired goods across the 13-kilometre-long Grand Portage, bloodshot-eyed voyageurs would enter the 4,600-square-kilometre watery network of Quetico—lakes and rivers which drain north to Hudson Bay and the Arctic. A first-timer crossing this height of land would be awarded a black feather and be baptized an homme du nord—before paddling a few more thousand kilometres to spend a cold, lonely winter at a forgotten northern post.

The best way to recreate the voyageur experience through Quetico is to take a week to paddle the 125-kilometre French Lake to Cache Lake loop. Starting at the French Lake access point on Highway 11, the route follows Baptism Creek to Baptism Lake—named after the voyageurs’ black feather ceremony. From here, you’ll pass through nine lakes before returning to French Lake via Pickerel Lake. With nearly 12 kilometres of portages—some rocky, some wet—you’ll earn your black feather.