Isle Royale National Park is home to the longest-running study of any predator-prey system in the world––a dynamic between wolves and moose. Yet, as we finally reached Belle Isle––a serene campsite nestled in a picturesque cove––it wasn’t the wolves I worried about.

Onshore, a weathered fisherman held his faded blue and white VHF radio to the sky as our group huddled together, straining to hear a crackling voice deliver unwelcome news. Wind gusts were forecast to reach 30 knots the following afternoon, swells topping eight feet.

The old man could only shake his head.

“When that east wind comes whipping right into this bay, that’s not good.” He told us his name was Dave, and he would know—he had been coming on fishing trips to Isle Royale for three decades.

I looked around at the concerned faces of our team. Photographer Aaron Black-Schmidt and I were joined by North Carolina-based paddlers Andrew Koch and Olivia Harrell. Our squad was on day five of a week-long SUP expedition, but eight-foot swells were not part of the itinerary.

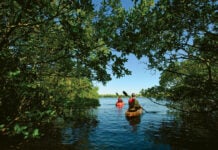

When Aaron first proposed taking 14-foot inflatable standup paddleboards to Isle Royale, it seemed like a no-brainer. Exploring a remote island in the middle of the world’s largest lake would be the ultimate adventure.

“When I saw you guys come around the point, I almost fell over,” said Dave. “I never thought I’d see paddleboards out here. But I thought the same thing 20 years ago when I saw kayaks for the first time.”

Located in northern Lake Superior, Isle Royale features more than 200 square miles of lush forest, pristine lakes and majestic shoreline. Made up of more than 450 smaller islands, this freshwater archipelago holds the unique distinction of being the least visited but most revisited national park in the continental United States.

Dave first came to Isle Royale in 1989 for a fishing trip. He’s only missed one summer since that maiden voyage. Listening to him talk of the island, we got a sense of what this place meant to him. It was his escape.

“I put everything I do into this log right here,” said Dave. “You guys are in here.”

He wasn’t the only one to journal about his experience on the island. A dusty old notebook in the corner of a rain shelter at our Belle Isle campsite revealed hand-written stories from fellow paddlers. Thumbing through the tales, there was one line that I kept coming back to.

“I’ve forgotten how loud silence is, stress doesn’t exist out here.”

With cell service non-existent, the constant barrage of push notifications, emails and text messages was replaced by conversation, reflection and appreciation for Isle Royale’s confounding beauty. We could plan our lives based on the light in the sky, not a number on the clock.

Only 24 hours prior, our crew had been paddling deep into Duncan Bay––a secluded, paddle-in-only campsite with fellow humans nowhere in sight.

“You want the lake view or the enchanted forest?” Andrew asked Olivia after surveying the lodging situation at Duncan. Andrew’s question wasn’t hyperbole. I looked up at the wall of my wooden rain shelter––the lake view option––and noticed three words carved into the weathered wood: Too Much Happiness. Later that night, I drifted off to the psychedelic sound of loon calls echoing through Duncan Bay.

Today began with a magnificent paddle from Duncan Bay to Belle Isle. With the wind at our backs, we enjoyed a downwind run through a spectacular open channel. Craggy coastline with yellow and orange fissures loomed to our left, primitive and untouched forest towered to our right and a bald eagle soared overhead.

After setting up camp in Belle Isle and making a plan for the following day, we tossed logs into an old stone fireplace once enjoyed by guests of the Belle Isle Resort. Before becoming a national park in 1931, Isle Royale had a long history of commercial fishing, mining and resorts dating back to the early 1800s. Belle Isle Resort opened in 1912 and featured a lodge, 28 cottages, a nine-hole golf course, a tennis court and shuffleboard courts.

Now the fireplace is all that remains; nature has reclaimed the entire island.

As conversation and golden embers began to dwindle, I looked out at the calm bay illuminated by brilliant moonlight. Would the next day bring howling winds and overhead swell like the weather forecast predicted? It was a perfectly still night, but the concern on Dave’s face from earlier that afternoon was unsettling.

The next morning, I opened my eyes to brilliant streaks of amber and red across a bay of glass. The sun was yet to crest above the tree line but Olivia and Andrew were already paddling, relishing the opportunity to witness nature’s masterpiece from the water. I grabbed my board and paddled out to a tiny island at the mouth of the cove, the silence broken only by the faint sound of my board gliding across the golden water.

Back on shore, Dave was unfazed by one of the most magnificent sunrises we had ever seen. No doubt, it was one of many he’s had the fortune of witnessing out here.

“Those east winds can come up quick,” he warned again, while haphazardly throwing piles of camping and fishing gear into his small motorboat. “I’ll be back in Rock Harbor in 40 minutes.”

Leaving Belle Isle wasn’t easy. Despite the pristine morning conditions, we chose to heed the warning of a man who’d been coming out here for 30 years. It was only a few strokes before we got one final taste of Belle Isle magic.

“There’s a beaver at your six o’clock,” said Aaron.

Bidding farewell to the beaver, Belle Isle and life on the edge, we began our journey back to Rock Harbor––the main hub of civilization on the east end of the Isle Royale and the beginning and end of most trips.

Despite running low on energy, this was a race against the weather we had to win. With winds picking up, we used a draft train to cross Duncan Bay and reach our final challenge, the Greenstone Ridge portage. The narrow trail features grueling climbs, treacherous downhills and hairpin turns, not the ideal combination when carrying a 14-foot paddleboard with nearly 100 pounds of drybags strapped to chests and backs.

We arrived back in Rock Harbor in mid-afternoon, with the storm still brewing out on Lake Superior. We all sat on our boards and took a few minutes to appreciate the moment.

Maps, photos and videos may entice people to visit Isle Royale, but it’s the sacred solitude and deafening silence bringing them back.

By dusk, I wondered whether we made the right call to leave the extraordinary beauty of Belle Isle. Spotting Dave’s small boat back in the harbor, I noticed the trees had begun to whistle. Within an hour, our three-walled shelter was assaulted by heavy rain and wind. And above the din of the storm, we could hear the swell crashing against the rocky shoreline.

Dave was right; those east winds do come up quickly.

This article was first published inPaddling MagazineIssue 62. Subscribe toPaddling Magazine’s print and digital editions here , or browse the archives here.

Jack Haworth is an avid paddleboarder and social media editor at Men’s Journal.