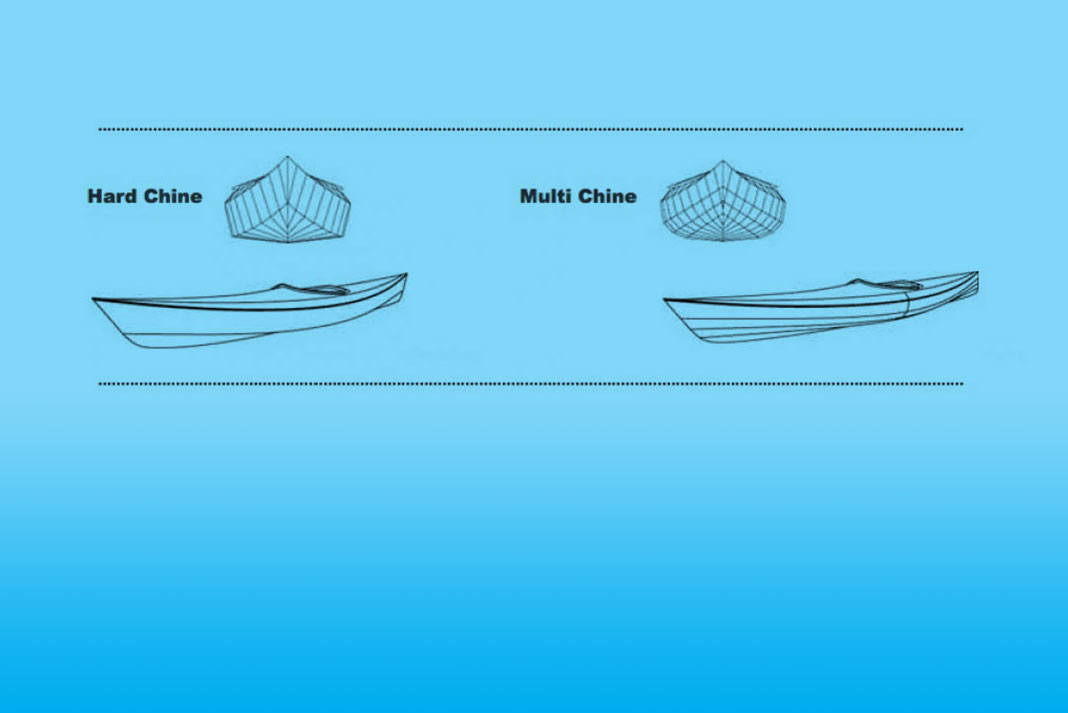

First, some terminology: Chine refers to the area where the sidewall of the kayak meets the bottom of the hull. A soft-chine boat exhibits gentle curves, while a hard- or multi-chine boat has abrupt edges.

The history of boat chines in kayak design

The early skin kayaks of the Arctic relied on wooden ribs and longitudinal stringers for form. Those stringers were responsible for the single hard-chine, V-shaped hull of the Inuit or Greenland-style kayak and the multiple hard chines of the Aleutian baidarka design. It wasn’t until the advent of fiberglass and plastic that builders designed rounded and shallow-arch hulls without pronounced edges—initially for whitewater slalom.

Hard chines in sea kayaking

According to John Lockwood of Pygmy Kayaks in Port Townsend, Washington, hard chines enable a sea kayak to carve crisper turns. When the paddler shifts her weight to tilt the boat, the sharp angles of a hard- or multi-chine hull effectively become a curved keel. Think of what happens when you engage the edge of a parabolic ski or snowboard—it’s essentially the same phenomenon as when a tilted kayak moves through the water.

Advantages in turning and cruising

Lockwood says that the turning motion is enhanced in a single hard-chine hull; these designs will also turn with less angle of tilt. Lockwood’s calculations demonstrate that if all design variables are made equal, a multi-chine hull has 3.2 percent less wetted surface (and therefore less water resistance) than a hard-chine hull, and so is about 3.2 per cent more efficient at cruising speeds. Any difference in wetted surface between multi-chine and soft-chine hulls is even subtler, however a rounded hull will not offer the same maneuverability on edge.

What chine is it? | Feature Image: Pygmy Kayaks

“Lockwood’s calculations demonstrate that if all design variables are made equal, a multi-chine hull has 3.2 percent less wetted surface (and therefore less water resistance) than a hard-chine hull, and so is about 3.2 per cent more efficient at cruising speeds.”

I’m not sure this is accurate, as the wetted surface contributes to skin friction, but not form friction, which I believe is the majority of the resistance when paddling (though skin friction is relatively constant and form friction increases exponentially with speed). As an extreme example, a 10′ rec kayak has less wetted surface than a surfski, but is not faster. The formula and arithmetic needed is beyond me, but I would estimate that maybe the hard-chine hull speed for a given effort might be less than half a percent slower. John Winters seems to know his stuff: http://www.greenval.com/shape_part1.html