Surviving self-doubt, limited skills and a busy schedule Adventure Kayak’s intrepid editor and rookie boat builder, Virginia Marshall, learns that bringing a wood kayak into the world takes passion, persistence and above all, patience. Which, as it turns out, is not her strongest suit.

What it’s like to build a Pygmy kayak

“I really believe John Lockwood is the best kayak designer in the world,” boat-building instructor Dan Jones proclaims on the first day of the Pygmy kayak workshop I’ve traveled to southeastern Ohio to attend. “His boats just work.”

Jones’ praise for Pygmy Boats’ 73-year-old founder and designer is a sentiment I’ll hear him repeat to the stream of appreciative visitors who drop into the workshop throughout our six-day course. Jones, 71, should know—he’s assembled 14 of Pygmy’s wood kayak kits himself and assisted friends and students with a dozen more.

So I’m surprised to learn he’d never paddled a kayak before building his first Pygmy—the Queen Charlotte, a higher volume tripper with the lines of a traditional Greenlandic skin-on-frame kayak—in 1989 while living near the Maine coast. After slipping it into the frigid Atlantic to quietly explore among fog-shrouded archipelagos, Jones was hooked.

The Queen Charlotte stayed behind with a friend when Jones moved west to Marietta, Ohio, but more Pygmys soon followed.

Heading south beyond the sprawling congestion of Cleveland and Columbus, I climb into the verdant hills and secreted valleys of Appalachia and roll off the I-77 into historic Marietta, a town of around 12,000 founded in 1788 by veterans of the Revolutionary War.

I meet up with Jones and his partner and co-instructor, Teresa Griffith, 59, out front of our unconventional workshop—a former J.C. Penny downtown department store. Just down the block, the Muskingum River slides lazily past leafy, redbrick streets lined with immaculate Victorian homes. In the dusty, disused accounting offices on the second floor, tall windows stream sunlight into a long room containing twin worktables and the piles of plywood sticks that I and one other student will transform into kayaks.

Build a boat on your own, or with a workshop

For about half the price of a premium plastic kayak—or a quarter the cost of a comparably lightweight, high-performance composite boat—Pygmy kayak kits include pre-cut, plantation-grown African mahogany plywood panels, swaths of silky fiberglass cloth, coils of wire, jugs of epoxy, bags of wood flour, latex gloves, syringes and a 46-page instruction manual.

The only other tools Pygmy’s comprehensive builder’s guide promises I’ll need for the job—drill, file, wire snippers, pliers, hot glue gun, clamps, sandpaper, masking tape, utility knife, paint rollers and foam brushes—I assemble from neglected corners of my basement, closets and kitchen drawers.

Most Pygmy paddlers are reasonably enterprising individuals with the gumption—builders need not have any woodworking experience, everyone I talk to is quick to point out—to tackle the 80- to 100-hour commitment of building a stitch-and-glue kayak on their own. Many folks diligently cobble together months of evenings and weekends to complete these masterpieces. Helpful staff at Pygmy’s oceanfront headquarters in Port Townsend are only a phone call away should builders run into difficulty as their kayaks take shape in basements, garages and home workshops.

For perennial procrastinators, however, or those who are nervous about building a kayak on their own, Pygmy began offering weeklong workshops at Port Townsend’s Northwest Maritime Center in 2010. The classes, which are limited to six participants, have sold out for the last five years.

Laura Prendergast, marketing director at Pygmy, says students come from many different backgrounds, from teachers and truck drivers, to doctors and do-it-yourselfers who love the idea of a rewarding vacation where they come home with a kayak.

“For a lot of people, joining a class removes their fear,” she explains. “We’ve found the typical incubation period from when people learn about our kits to when they actually build a boat is about four years. But with the classes, we’ve had people learn about us for the first time and say ‘sign me up’ that day.”

When I heard that Pygmy had expanded the workshops for 2015 to include venues in Maine, Florida, Oregon and Ohio—and that Jones, who loaned Adventure Kayak the lovingly crafted Pygmy Murrelet to review, would be teaching the Marietta class—I called Prendergast and registered without hesitation.

“You don’t need any skill to build these boats, just patience,” Jones told me on our first fateful meeting. “If I can do it, anyone can.”

Since Lockwood launched Pygmy Boats from his garage in Port Townsend, Washington, in 1987, his designs have multiplied and diversified to include a fleet of 22 different kayaks, a wood canoe and a wherry rowing boat. Each promises the resourceful self-sufficiency of its creator. Lockwood, a nomad turned anthropologist-computer programmer turned boat designer, built his first stitch-and-glue kayak in 1971 after a five-month stint living off the land in a homemade teepee on the wild shores of British Columbia’s Queen Charlotte Islands.

The story behind Pygmy Boats

It may be the more-fantastic-than-fiction trajectory of Lockwood’s life, as much as the allure of wooden boats, that captured Jones’ imagination, and mine. After several years of wandering the world’s wild places, first as a young itinerant and then serving in the military, Lockwood’s peregrinations ended abruptly in 1967 with a fall at a construction site, resulting in a shattered hip and a long-term dependence on crutches.

Four years later, armed with a Harvard education and a Klepper folding kayak—and seeking escape from academia, increasingly crowded wilderness and the limitations of his injury—Lockwood landed in the remote Queen Charlotte archipelago. The wood kayak that he built was light and tough to enable dragging over the islands’ barnacle-encrusted shores while hopping on his good leg.

The story might have ended there were it not for a decade-and-a-half journey that lead Lockwood south to Seattle, into the offices of IBM and Boeing as a computer programmer, and finally back to the water when he developed cutting-edge software for naval architecture. With this powerful tool, he could also design precision-cut plywood hulls on his personal computer. Lockwood sold three Queen Charlotte kits in 1986; a year later Pygmy was born and he shipped 45 kits to the company’s first crop of would-be builders.

Building a Pygmy boat

My first day in the workshop, I discover that I’m not quite as handy with a carpenter’s square, or as hopeless with a block planer, as I’d imagined. I’ve misused the former with some frequency, but I’ve never used a planer before beveling the edges on five of the kayak’s 15 delicate, plywood panels. Wood shavings fall in curlicues to the floor as the deck and hull panels are prepped to fit neatly together at the sheer line.

The 17-foot-long panels flop off either end of the table and must be carefully supported at this stage. “It’s the wood that gives a boat its shape and beauty,” says Jones, but four-millimeter plywood on its own is not particularly robust. “The fiberglass gives a boat strength and the epoxy binds everything together and makes the shell waterproof.”

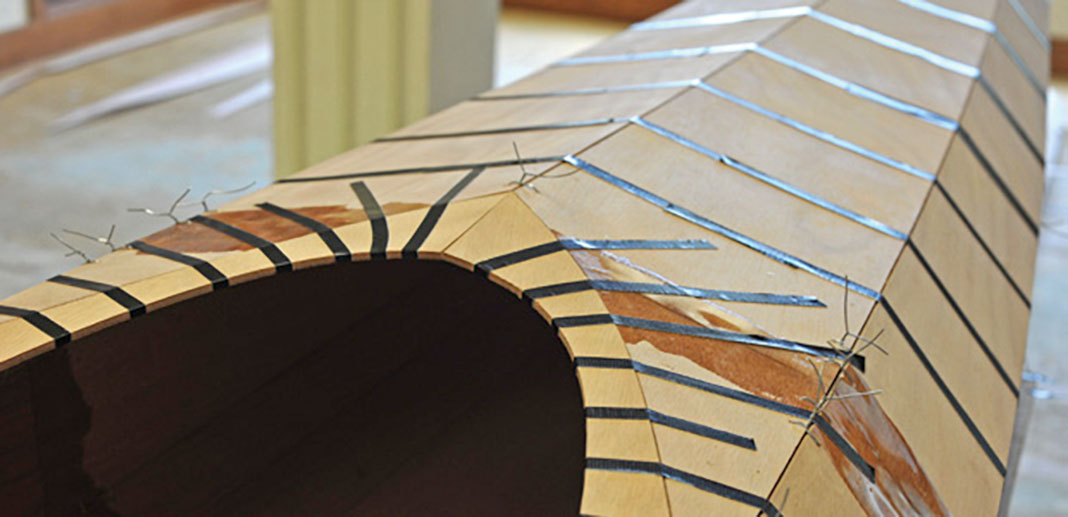

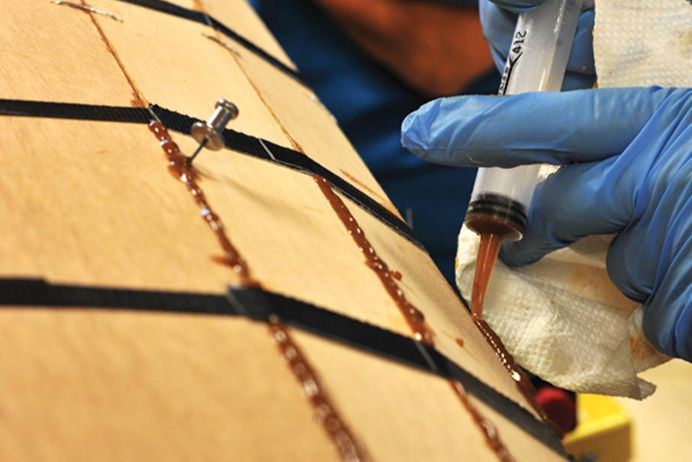

We’re using Pygmy’s pioneering new Gorilla Tape method rather than the classic stitch-and-glue assembly. Instead of the hundreds of painstakingly twisted pieces of wire used in the stitch method, strips of super-sticky tape placed every few inches hold the panels together before the seams are joined with epoxy. It’s faster, less fiddly and works well for the rapid build of a weeklong workshop.

After putting in a full day in the workshop, I join Jones and Griffith for a tour of Marietta from the water—down to the confluence of the Muskingum and mighty Ohio rivers, and upstream to view the town’s historic paddlewheelers. I paddle Jones’ beloved Osprey HP, his second Pygmy build and still his favorite. The HP is “straight and fast, and doesn’t turn worth a damn,” he tells me, “but I’ve been in the shit in that boat and it performed beautifully.”

The class’s only other student, Richard Webber, is a quiet, fit, 67-year-old who has driven three days cross-country from Boulder, Colorado to build his kayak under Jones and Griffith’s watchful tutelage. He looks surprisingly refreshed.

Webber unpacks his old tools from new Tupperware containers. He builds Greenland and Aleutian paddles in his spare time, he tells us, which he uses for rolling and other traditional tricks. Like me, he’s never built a boat before. Also like me, he’s building the Murrelet 4PD—a performance touring and rolling design that he paddled only briefly at Pygmy’s Port Townsend showroom. He’s unhurried and efficient. He says “darn,” not “damn it,” even when he breaks a wire or snaps his third 1/16th bit. My concerns that the class will feel like a race melt away. Even with only two students, the workshop has a collaborative feel rather than a competitive one.

Day two brings the new challenge of working with epoxy. With eight long strips forming the multiple chines and shallow V, my hull actually resembles a boat now—an overturned half-boat, but a vessel nonetheless. We mix epoxy thickened and fortified with wood flour and shoot the seams using dental syringes.

At day’s end, I’m cross-eyed and head sore from nine hours of focusing on seams six inches from my face. My feet hurt. But nobody complains. We’ve joined what Griffith calls the Pygmy cult—building these boats feels like a privilege, no matter how painstaking.

I’ve been in love with the Murrelet’s lines since I first laid eyes on Jones’ boat two-and-a-half years ago: the sweeping bow, the cutaway front deck, the way the rear deck scoops gracefully down behind the cockpit for effortless rolling.

Jones describes assembling the Murrelet’s intricate cockpit area as a “wrestling match,” but it flows together nearly seamlessly. Pygmy kits don’t require the wood to be tortured—bent or manipulated into form—but instead fit perfectly together like puzzle pieces. And like Lockwood’s designs, the panels are almost miraculously well engineered.

By day three I have a full boat, but the accomplishment is temporary. Tomorrow we’ll remove the deck to complete interior work, then put it back on (then take it off again). Each step is logical, methodical, necessary. I’m learning boat building involves nearly as much tearing down as building up. I’m learning patience.

The days begin to blur. Our concentration is so absolute, an hour can pass without a word being exchanged aside from brief instructions—or more often, Jones’ Socratic questioning, “What’s the next step?”

On day four, we roll epoxy over the inside of the deck. The resin brings out the manuka honey-hued beauty of the Okoume mahogany’s grain—what Pygmy calls a “bright finish.” Webber mentions maybe painting his hull later for an alternative finish. Sacrilege.

Day five’s main event is glassing the inside of the hull. First, however, the interior must be sanded to remove all bumps, divots and ridges. When it’s as perfectly smooth as a still pond, Jones calls in a friend and fellow builder from the Marietta Rowing and Cycling Club to assist with glassing. The fiberglass is a 24-foot-long by several feet wide roll, and it’s slippery as an eel. We drape it over the boat, coaxing it into the keel and chines.

“When you do your outside deck and hull at home, get some friends to help. Make it a glassing party,” advises Jones. “It just makes it so much easier. You want five people: two to roll on the epoxy, two to follow with squeegees and brushes to work out any air pockets, and one to mix epoxy.”

It’s a wonderful vision: the glue saturating the fiberglass and turning the cloth translucent to reveal the golden mahogany. Rollers fly, elbows bump, heads bow and the hull glows. My latex-clad fingers stick to the roller handle. When I try to pass it to someone, I find it’s glued to my hand.

“This is the most perfect inside hull glassing I’ve ever seen,” Jones says when we’ve finished with my kayak. Webber’s face crinkles into a smile. “I thought this was the practice boat,” he teases.

Taking it home

One week is just enough time to assemble the kayak’s basic structure. Major finishing steps like sanding and glassing the exterior, cutting hatches and installing the coaming and outfitting must still be completed in students’ basements and garages. Theoretically.

“We should offer follow-up classes for all the folks who take them home and never finish them,” muses Griffith. She cites students and friends who are still tinkering—or procrastinating— six months, a year and two years later.

Inwardly, I worry this will be me. “Well, life gets in the way,” Griffith concedes.

“Then you’ve got your priorities wrong,” Jones retorts, only half kidding.

Webber tells me that he plans to finish his boat as soon as he gets back to Colorado. “I want to paddle it this summer,” he enthuses. I think of all my other obligations when I return home— my priorities will be a juggling act. I hope I don’t drop the ball.

On the last night, Jones and Griffith invite both of us for dinner— delicious New Mexican cuisine, a throwback to Jones’ boyhood in Albuquerque, and Sangria with home-brewed Moscato wine. Over green chili sauce-drenched enchiladas, Jones reviews the steps we’ll follow to complete our boats, adding his own tips and tricks to the Pygmy manual.

Two weeks later, when I hit hour 16 of a marathon sanding session to prepare the kayak for final glassing, I’m wondering—as Webber did in class so many days ago—‘how smooth is smooth?’ This time, I don’t have Jones’ knowledgeable hands to caress the sanded seams and give a pleased nod or shake his head and join me with his own rasp.

Finally, I do the sensible thing. I call Jones for reassurance, then Webber.

Jones is sympathetic but firm. “Scraping the seams is a pain in the ass, it really is,” he admits, before coaching me on tools and technique. I’m starting to feel better.

Webber shares the highs and lows of his own sanding trials—from hours of fruitless hand sanding and resigning himself to hiding the imperfections with paint, to embracing the power sander and finally getting the hull fiberglass- and varnish-ready. “I’m anxious to get it in the water,” he concedes, but like me, he’s learning patience.

Before the course, Webber says he was intimidated by the idea of building a kayak on his own. Empowered by our time in the workshop, he’s pushed past those fears. “But I’m still feeling nervous about this next step,” he confesses.

I now feel much better. We promise to exchange photos of our finished kayaks at the end of the summer.

Joining this workshop, I realize, has brought more than just another kayak into my life—it’s also connected me with a wonderful community of builder-paddlers who, like my nascent Murrelet, I’ll cherish for years to come.

The author’s Pygmy kayak begins to take shape. | Feature photo: Virginia Marshall

This article was first published in the Fall 2015 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Fall 2015 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

Good article but i’m somewhat confused. Last I knew Pygmy closed down. Kits Re no longer available. Why are you publishing this now?

I bought and built 2 Pygmy Boats and buildt them. Can anyone tell by the serial number when that was 1PGPS145F009 and 1PGPS175H009

Why such a complicated design?

Typical, the deck, 4 pieces across it. They all have to be cut exactly. I’ve never done that with my designs, simply slap a bit of plywood across the kayak, lash it down to curve over the easily made laminated deck beams and wait until the epoxy is dry. Cut the excess width off with a handsaw. Not a jigsaw. Couldn’t be easier.

As for fibreglass cloth all over (and inside too?), that just adds to weight, a great deal of epoxy weight and cost and if repairs are needed, complicated. We only put cloth on the joins. Admittedly the oldest kayak I have was built in 1983 so possibly it will only last 100 years.