Earlier this spring the Lawrence & Memorial Hospital in New London, Connecticut, was locked down while police searched the building for an armed man. Apparently, an emergency department nurse had spotted a double-barrelled shotgun poking out of the top of a worn and tattered backpack. She alerted hospital management, management notified the police, the police called in the SWAT team and the SWAT team took the building—like the final scene in a Bruce Willis action movie.

Meanwhile in the lunchroom, two hospital employees chatted about their weekends. One pulled a black, carbon fibre breakdown kayak paddle from the suspect backpack and thanked his friend for loaning it to him. Then they rinsed their coffee mugs and walked into the hall to start their shifts.

The hospital officials and the authorities called it an honest mistake. Surely the nurse did the right thing reporting what she thought was a shotgun. No charges were laid, though the two hospital workers were asked to leave their paddles at home.

Soon after hearing this story, I was flying from Vancouver to Toronto. I travel light and seldom check any bags. I had just a carry-on, a laptop bag and a canoe paddle. I’d broken the shaft on a river trip last summer and shipped it west for repair; I picked it up while I was in Vancouver to save shipping costs. At the security corral I placed my bags, shoes, keys, coins and my repaired paddle on the conveyor belt and walked through the doorframe to the lady with the wand.

Maybe our new heritage minister should launch a national program designed to put our youth more in touch with this country’s heritage.

Big signs are posted all over the airport, signs showing the items banned from air travel. You can’t board an airplane carrying jackknives, mace, chainsaws, or fire extinguishers. For the record, paddles are not on the sign.

Soon I was kneeling on the carpet in front of a half-dozen security staff who’d gathered around me in a semicircle. None of them knew what I was doing. I said it was the J stroke. Empty faces.

The conveyors were stopped, no one was checking through. People were going to miss flights. “Oh for Christ’s sake,” some guy in a suit shouted from the lineup. “He’s canoeing.”

Now here’s some wonderful irony. Canada’s national carrier doesn’t allow you to carry on a paddle. Yet, for hundreds of years the canoe was the national carrier. I had to explain to the staff of Air Canada that my so-called weapon was not a weapon but a canoe paddle. How sad.

I wonder how Pierre Trudeau, our paddling prime minister, or Beverley J. Oda, our new federal heritage minister, would feel about this. There is no symbol more Canadian than a canoe and paddle.

Maybe our new heritage minister should launch a national program designed to put our youth more in touch with this country’s heritage. After a full royal commission it would be written in a 600-page document that children should go away for a couple of weeks each summer and learn to paddle and explore, by canoe, nearby lakes and rivers. The report would recommend that they go to summer camp, a place where rows of canoes line the water’s edge and racks of weapons, just like mine, are for children to play with so that someday when they are standing in an airport they’ll remember that there are at least two ways to travel across Canada.

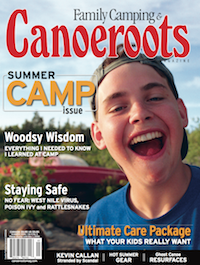

This article first appeared in the Summer 2006 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.