“I think this is Bear Bite Creek,” I say with confidence, having followed our progress on the map since a hunting cabin 20 minutes ago. “I don’t think so,” says Emily, looking at the bends in the river. But the perpetually shifting braided channels of the Tatshenshini River are confusing. Simultaneously, our heads swivel to look at Adam. He pulls a gadget out of his bag and gives me a thumbs down. I’m wrong. It’s an unnamed tributary a mile upstream of Bear Bite Creek. So much for old school map skills.

The rise, fall and rise of handheld GPS

Thirty-five years ago, Magellan released the NAV 1000, the first handheld GPS. In an era of chart and compass, the promises of handheld electronic navigation were riveting for fog-bound sea kayakers.

But early GPS overpromised.

When I was leading outdoor trips, our gadget-freak boss splurged and bought one for us (we’d asked for a cell phone). We could never get a signal. My, how you’ve grown.

Now we use satellite messengers that send campsite info to our friends. I carry an EPIRB in my PFD. On a recent trip, a friend whipped out a tiny Kindle, which held a 700-page pilot’s manual and several other books she was working through. Recharging devices is a camp chore like filtering water and hanging food. And the NAV 1000, with its 80s clunkiness and nonfunctionality, ushered it all in. Now it’s mostly a relic.

Do-it-all smartphones step into the gap

Like cameras, rolodexes and calendars, electronic navigation devices have been made practically obsolete by smartphones. The gadget Adam pulled out of his bag in the Yukon Territory wilderness wasn’t a GPS. It was his iPhone.

I can download the maps for a hike or paddling charts in the car en route. And I can print out custom nautical and topo hybrid maps on free sites like CalTopo. I can even dial in sun exposure to select a camp with maximum afternoon sun for beach basking. When I do use a GPS, the clunky early-2000s era interface makes it agonizingly slow to type in a waypoint. More often than not, the GPS ends up left behind in the drawer.

This may be changing. Last weekend, I swung by the kayak shop to pick up a chart of a remote island chain. “I’m surprised we have this one,” my friend Andrew joked as he handed it to me. “We don’t sell many charts, except the ones we sell to you.”

Nautical charts go paperless

In February 2022, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced it was discontinuing paper nautical charts entirely, shifting to electronic formats meant for chartplotters on recreational boats or the sophisticated navigational systems of commercial craft.

What does that mean for sea kayakers?

You’ll either have to print out your own paper charts from their currently nonfunctional prototype interface, or use a device that can process nautical electronic data. And what does that mean for the NAV 1000’s progeny? They may be spending less time in the drawer.

Neil Schulman writes, photographs and paddles from somewhere around 45.34.12 N, 122.38.54 W, according to his GPS. His first article for Rapid Media was published in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak.

“The MAGELLAN NAV 1000 is a single channel receiver. Data is received from one satellite, then from another and so on. It is very interesting to watch a NAV 1000 initializing. First the satellite almanac has to be loaded. A satellite can be chosen or the receiver will search one. After an initial position has been entered the NAV 1000 searches for satellites, one after another. Then it will receive data, one after another. Then ‘computing’ is displayed for a while and with luck a position is calculated.”—retro-gps.info

And this is a Garmin inReach Explorer+, both a measure of how far we’ve come. Get it? | Feature photo: Chris Korbulic

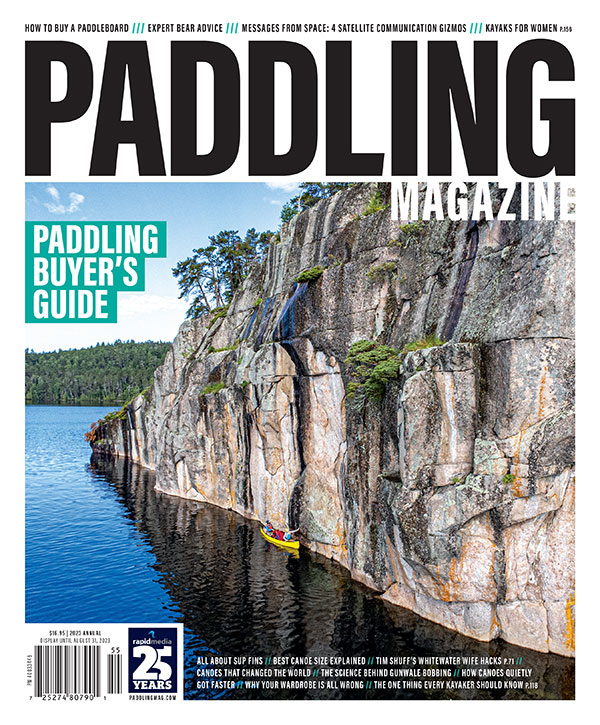

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

the problem with the smartphones is they deplete their batteries rather quickly

my old handheld GPS works for 20hours on a pair of AAs

I guess it all depends on how long one is out there

Regrettably, my iPhone isn’t very waterproof so I prefer my GPS, which is. No worry if it’s mounted on a thwart and splashed in rapids or submerged in a capsize. I’ve found that re-charging phones, via a compact battery pack is awkward when it’s raining or I’m canoeing heaving lakes or rapids. And solar charging in camp is only practical if the sun is shining, which it often isn’t. Consequently, I still rely on my Garmin Oregon which, as mentioned above, does at least 20 hours on AA’s which can be changed out instantly. I also think my GPS is, more rugged than my phone. And even if it’s not, it can be replaced for half the price of my iPhone. I’m old school and thus still prefer a full size USGS or Canadian topo map (as the case may be) plus a hand-held GPS and an old-fashioned orienteering style needle compass. With these, it’s nearly impossible to get lost. But, paddle tripping is a sport, and to each his/her own.

I disagree with the premise that changes in NOAA chart policies will result in a resurgence of handheld GPS units for paddlers. There are plenty of smartphone apps that can plot electronic nautical charts (ENCs) just like the old handheld GPS devices. I’ve found that in airplane mode I can go three days or so without recharging my phone, which stays inside a waterproof floating case while on the water. The biggest downside of the phone is that it can be hard to use with wet hands.