No circumstances conspired to turn me into a kayaker. I grew up in the city, far from the water. Yet I knew I wanted to go sea kayaking long before I ever had the chance to try it. Sometime in the 1980s, on a family trip to Cape Cod, I caught my first glimpse of a sea kayak hanging from the ceiling of a tourist shop.

The juxtaposition of the unfamiliar vastness of the ocean we’d been visiting and the notion of launching into it in such a tiny and exposed watercraft was intoxicating. Kayaking seemed like the appropriate response to the infiniteness of the ocean, and to me symbolized the kind of relationship I wanted to have with the world—one composed of unfiltered, direct, adventurous experiences.

Hardwired: Why true kayakers are born, not made

Even though it would be more than a decade until I actually sat in the cockpit of a sea kayak, the idea of me as a sea kayaker gripped me. I started clipping pictures of kayaks out of magazines and taping them all over the walls of the house, as if to declare to myself and my family that this destiny would not be forgotten. As motivation, that’s as intrinsic as it comes.

Other people come to their outdoor passions similarly. The environment, or the activity, ignites something already deep inside. For some, it’s paddling, for others, it’s hiking or climbing in the mountains.

Falling in love with the landscape

I’m enjoying the new memoir by the California-based science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson, The High Sierra: A Love Story, about his lifelong affair with the Sierra Nevada. He didn’t start out as a backpacker. Like me, he grew up in the suburbs. But everything changed in 1973 when he and some university friends drove to a trailhead, dropped acid and went for a hike.

“I didn’t know that my life had changed for the good,” he writes. “But I did know I had just lived one of the greatest days of my life. And I knew that this granite world, holding me in its cupped hands as I lay on it, glowing luminously in the moonlight, was a magic place. I loved it. I loved it. That feeling has never gone away. I trust now that it never will.” He went on to make hundreds of hiking trips into the mountains known as the Range of Light.

Robinson is talking about falling in love with a place, a specific mountain range, not backpacking per se. But outdoor sports are wrapped up in the experience of landscape in a way that’s difficult to disentangle.

Similarly, sea kayaking is about a relationship with the watery landscape. It’s a feeling.

“That feeling is one of the things I want to write about here. Crazy love. Some kind of joy,” Robinson gushes near the beginning of his 537 pages. “But what struck me most that day, and has lingered since in me, was a stupendous sensation of significance…what I was seeing was more than real.”

An innate propensity for paddling?

When I wrote a master’s thesis about wilderness adventure, that’s what people told me they were after: “ultimate reality.” Something too deep for the usual scientific research to grasp. The Outdoor Foundation’s 2015 Special Report on Paddlesports found 72 percent of kayakers are motivated “to get exercise.” And so on. Yadda yadda. Sponsored by The Coleman Company, Inc. that information might help you sell kayaks, but it doesn’t answer the question of what makes people paddlers in the first place.

No, I’m talking about paddling as a transformational act. People whose first glimpse changes them “for good.” As in for the better. As in forever.

In the 1978 classic of paddling literature, The Starship and the Canoe, writer Kenneth Brower compares the famous astrophysicist Freeman Dyson and his hippie son George, whose trajectories represent wildly divergent responses to a planet in crisis. Freeman looks to outer space: humans must colonize other planets. Dyson takes a back-to-the-land, low-tech approach: he retreats to the Pacific Northwest, lives in a treehouse and starts building kayaks fashioned after Aleut baidarkas.

Certainly the Princeton professor didn’t set out to turn his son into a kayaker. There must have been something innate in George that made him choose that watery path, like some genetic predisposition waiting to be expressed.

Like a duck to water

Sometimes people can see this propensity in you early, before you even discover it in yourself. There was an old man named Peter who went to my parents’ church and saw me grow up, though I hardly spoke to him. In high school I wrote an essay for the newspaper full of angst about living in the city disconnected from nature—the same stuff I write now. Peter read it and asked if he could take me out to lunch. He rambled about places he’d traveled and asked about my plans after school. He gently suggested I postpone settling down and take some itinerant jobs. A berth on a transoceanic freighter might be an interesting way to see the world. That was a weird conversation, I thought.

As the years went on, I studied outdoor recreation, moved to the West Coast, and worked as a tree planter, canoe trip guide and forest firefighter. The reports Peter got from my parents must have confirmed he’d read me correctly.

I don’t know if Peter ever kayaked, but I think he too was a kayaker in spirit—born, not made—and he recognized a kindred one when he saw it. Before he died he mailed me a poem out of the blue. It’s a popular one, called The Little Duck, by Donald Babcock:

“Now we’re ready to look at something pretty special

It is a duck

riding the ocean a hundred feet beyond the surf. […]

And what does he do, I ask you?

He sits down in it!

He reposes in the immediate as if it were infinity

—which it is.

He has made himself part of the boundless

by easing himself into just where it touches him. […]”

Whenever I think of that poem I think of Peter, how he saw some spark in me that he connected to a feeling in himself. It’s the spark that flared when I saw that kayak in Cape Cod.

Years later I collected the earnings from all those odd jobs, drove to Granville Island in Vancouver and walked into the Ecomarine store. I pointed at the sea kayak hanging from the ceiling and asked the staff to help load it onto my truck.

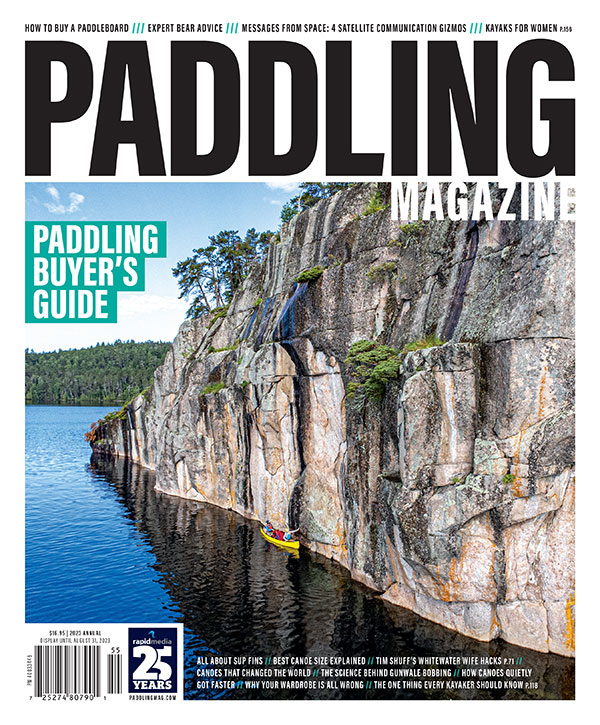

Either way, it’s your parents’ fault. | Feature photo: Adam Hill

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

Thanks for a lovely article! I’ve often wondered about the relationship between psychedelics and the wilderness experience. You don’t have to dig far into the literature to find plenty of thought-provoking examples. I certainly don’t recommend ingesting psilocybin or LSD and going for a hike, however. But I think the concept of guided immersion in nature while using such substances holds promise for personal growth and therapy.

Tim’s claim is that true kayakers are born, not made, yet provides no proof whatsoever. He then appears to claim that HE was a born kayaker. Is he trying to start his own kayak cult? How do we sign up?