It takes us seven and a half hours to slog across. We silently wonder how we’ll continue for another 650 kilometers but neither of us dare say a word.

A FUN CHALLENGE

Back in the depths of winter, the Yukon River Quest (YRQ) sounded like a fun challenge to my partner, Geoff, and me. It was the cabin fever talking. I should have known, because despite being the canoe-crazy one in the relationship, this was all Geoff’s idea.

The longest annual canoe and kayak race in the world, the YRQ takes paddlers 715 kilometers from Whitehorse to Dawson on the remote Yukon River in northern Canada. There are just 10 hours of mandatory rest stops along the way, and racers must finish in 84 hours.

Competitors fight the elements, the clock and each other, but by far the hardest battle plays out in each boat as sleep deprivation and exhaustion take their toll.

This same route transported tens of thousands of prospectors during the Klondike Gold Rush between 1897 and 1899. We’ve come for the same reason as those stampeders—the promise of adventure and glory.

TRAINING FOR THE RACE

In the spring, I browsed the competitor bio section on the YRQ website. It was daunting. There were Ironman participants, past winners and expedition paddlers with marathon CVs as long as their bent-shaft blades. Geoff and I hadn’t paddled more than 30 kilometers on flatwater in a day.

Soon after ice-out we began a regime of endurance training on weekends and short, brutal interval sessions on weekdays at 5:30 a.m. With concerning regularity one of us hit snooze and we fell back asleep.

Most troubling was our stroke rate: marathon canoeists paddle 60 to 80 strokes per minute; trippers typically average just 25 to 30. To get our cadence to a competitive level we bought ultralight carbon fiber bent shaft blades from Grey Owl Paddles and enlisted 71-year-old Bob Vincent, a decorated marathon canoeist, who’s been known to compete in a matching red and white polka dot Spandex suit. For two hours on a sunny May morning, Geoff and I had Bob and fellow coach Gwyn Hayman to ourselves. They offered first-hand tips, variations for steering and advice on quickening the recovery phase of our strokes. It helped.

By early June we could easily hold 54 strokes per minute, though we still felt galaxies out of our league. Our focus wasn’t on winning—we just wanted to finish in the time limit.

We settled on a deceptively simple strategy: Just keep paddling.

CHECK IT OFF THE BUCKET LIST

Like many fantastically outlandish ideas before it, the Yukon River Quest was hatched over drinks in a dive bar. Created to celebrate the centennial of the gold rush, the first race traced the 700-mile route stampeders took from Dyea, Alaska, over the Chilkoot Trail and down the fabled river to Dawson, Yukon.

To further mimic the struggle of the stampeders, YRQ co-founder Jeff Brady had participants carry 50 pounds of useless gold rush-era gear, including a cast iron frying pan, hatchet, shovel, hammer and five pounds each of nails, beans and flour. Most teams made it in five days.

The pre-Whitehorse leg and unnecessary equipment regulation were dropped after 1998, creating the bona-fide paddling marathon we know today. Since then, almost 2,500 canoeists and kayakers have competed.

“People come to the Yukon River Quest because they want to say they’ve done it and check it off the bucket list,” says Brady, who will compete in his sixth race this summer. “The real challenge is for people to stay up and keep paddling. The vision of paddling under the midnight sun is beautiful, but what your body goes though is horrific.”

THE END OF LEG 1

We arrive to a mandatory gear check the morning of the race laden with some 150 pounds of equipment, water and food. We’ve prepped 70 small meals each, one for every hour we expect to be on the river. PB&J sandwiches, baguettes, cheese, cookies, fruit cups, granola bars, beef jerky, grapes and one large, cold, cheese pizza come aboard.

“This is the hardest thing you’ll ever do,” warns 56-year-old John Little, a 10-time YRQ veteran we meet at the start line. “But it’s good to do something like this once a year and remind yourself what you’re made of.”

“If you can do this, you can do anything,” Little adds.

Little’s words echo in my mind 10.5 hours later, back at the end of Lake Laberge. We pull on warmer clothes for the cool night ahead. A quarter of teams scratch each year and hypothermia is the number one reason for dropping out.

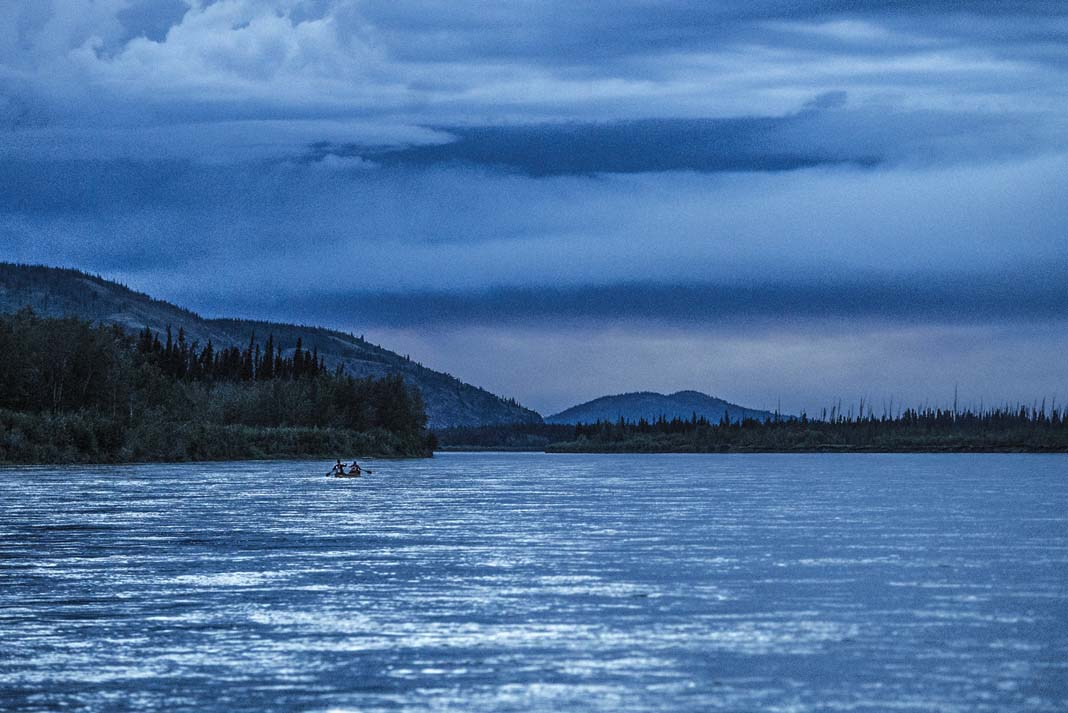

Entering the jade green current is refreshing after lake travel. This far south, the sky darkens to twilight between midnight and 4 a.m. Mist blots out the shining half-moon. We’re alone.

Fish flies come out in force, covering our bodies and gear. Grayling leap alongside our canoe while bats twist and dive to feed. It’s beautiful, but soon exhaustion and hypothermia stalk us through the night. Our only defense is to eat, drink and keep paddling. We agree the take-out pizza was an exceptionally good idea.

Mid-morning and hollow-eyed we arrive at the Big Salmon River monitoring point. A voluntary rest stop, there’s only a few paddlers here, all in obvious discomfort. Some are sick, others sore, nauseous and demoralized. No one says the word scratch, but most are considering it. “We have to get out of here,” Geoff says to me. I tape up blisters forming on my palms and we get back on the water. Just keep paddling.

We reach the mandatory rest stop Carmacks at 7:24 p.m. We’ve traveled 301 kilometers in 30 hours.

JUST 415 KILOMETRES TO GO

Sleep deprevation is a funny thing. Just 20 hours awake and the average adult begins to function as though they’ve had two alcoholic drinks.

Continue to stay awake and simple tasks like bandaging a blister or navigating a channel, begin to seem as insurmountable as K2. Navy SEAL sergeants leading recruits through training exercises during the notoriously sleep-deprived and aptly named Hell Week report that simple obstacles, like a fence, have reduced grown men to tears.

Confusion, vision disturbances, tremors, emotional volatility. It’s sleep deprivation, rather than distance, that breaks paddlers on the Quest. Hallucinations are common, a sign that the brain is not interpreting stimuli correctly.

Many paddlers reported the same apparitions I saw—canoes pulled up on shore, people standing on the banks, giant illegible words carved into rock walls. Otters revealed themselves to be floating sticks, shore-side cabins gave way to the crisscross of downed trees, the voice at our backs was always just the wind.

Situated roughly halfway through the race, the Coal Mine Campground in tiny Carmacks is the first opportunity racers have to pause the clock and rest for seven hours.

When we arrive, most racers are sleeping. The ground is covered in an explosion of brightly colored canoes, kayaks and dry bags from four-dozen teams. The leaders have already come and gone, arriving a full 12 hours ahead of us. Their speed is bewildering.

Obviously out of the running for a podium finish and feeling absolutely wrecked, we decide to stay longer than necessary at Carmacks to get more sleep. When we wake, a full seven hours later, only eight boats remain.

Though sore, we’re invigorated by our night of rest. We get back on the water at 5:25 a.m.—just 415 kilometers to go. Cheery volunteers promise the worst is behind us. Liars.

A couple hours outside Carmacks, we approach Five Finger Rapids, a major obstacle for gold rush stampeders where steamwheelers wrecked and men died. Due to low water levels, it’s the first year where no boats capsize.

As the river valley meanders, we hopscotch under rain clouds, spotting moose, beavers and a porcupine. We meet only one paddler who isn’t racing. This grizzled canoeist is on his way to the Bering Sea, three weeks distant. A yellow Lab dozes in his cedarstrip, chin on the gunwale. We tell the paddler about the race, he tells us we’re crazy.

EAT, DRINK, PADDLE

Evening brings a 50 mph headwind. We paddle directly into it for hours. Some competitors pull off the river to wait it out and we begin to catch up and pass a handful of boats. Creedence and Stan Rogers blast from our waterproof speakers, and when we get tired of them we take turns singing—terribly.

It’s dusky and drizzling around midnight when the canoe wobbles and I glance back. Geoff is sitting wide-eyed and upright, his paddle across his knees. “Did you just fall asleep?” I ask. He gives a silent nod. A sleepy lean of Geoff’s 6’8” frame would certainly pitch us into the frigid water, and the river here is wide, with steep banks and swift current. A swim would be dangerous, and the end of the race. “Eat. Drink. Paddle,” I say. Energy in, energy out—consuming and moving is the only way to stay awake.

Close to 3 a.m. we spot the campfire at Kirkman Creek, a tiny flickering beacon in the blue and black half-night. We’re elated to have made it. This is a mandatory three-hour stop before the final push to Dawson. A jovial man dressed head to toe in camo welcomes us; another with a Yosemite Sam mustache offers hot soup.

We set up our tent and take off soaked clothes, feeling blessed for the opportunity to drop into unconsciousness. Climbing naked into my sleeping bag, the heaviness of sleep drowns me. My hands throb, my back aches, my skin is cold and clammy. I’m exhausted, yet filled with a dreamy, joyous feeling radiating from the middle of my stomach. This is an adventure in one of my favorite places in the world with the man I love. “I’m so happy,” I tell Geoff. And then I’m out.

JUST KEEP PADDLING

Two-and-a-half hours later, The “Good morning” trill of a volunteer comes too soon. I sit but can’t summon the motivation for anything more. Exhaustion-induced euphoria has evaporated. It’s cold. Aches have stiffened. Even more disheartening, it’s still raining. Geoff buries his face in the wall of the tent. We both ask if the other wants to continue.

“We’d wake people and they’d get angry, they’d want to fight us,” longtime Kirkman Creek volunteer Greg Spenner told us later. “Others were confused—they didn’t know where they were, or why they were there.”

We know why we’re here. It’s just 150 kilometers to Dawson, nine more map pages. There’s nothing to do but paddle. We pull on damp clothes, pack up soaked gear and push off under a grey sky. Though it’s just a fraction of the distance, the final section of the race is the crux for many. Exhaustion, slow current and navigating islands and gravel bars as the river widens takes its toll. I can barely keep my eyes open. The joy of adventure is forgotten; it’s the promise of real sleep that keeps us doggedly stroking away.

River curves stretch for mind-bending miles; we chase current only to have it seemingly disappear. I have a rushing sound in my ears and the visual sensation of starring in a stop motion film. Geoff is downing Advil to battle seizing muscles. We round a bend just before the 60-Mile checkpoint, the last of the race, and come face to face with a headwind so strong, whitecaps form as the river reverses on itself. Everything is loud and bright and astonishingly hard. I’m not sure whether to laugh or weep.

Just keep paddling.

When we finally spot the modest rooftops of Dawson, I feel kinship with the stampeders who must have seen a similar sight and felt the relief of respite at the end of a hard journey. There are cheers and a horn marking our arrival. We feel strong and weak, powerful and vulnerable.

It’s the first canoe trip where I’m happy to reach the take-out. It’s Saturday at 7:09 p.m. Our official finishing time is 69 hours. We had started paddling Wednesday at noon. We’re in 39th place of 58 teams. We hug, kiss and high-five. We are so done.

ADVENTURE, GLORY, AND GOLD

With its painted building facades and dusty roads, Dawson has succeeded in appearing pleasantly trapped in 1898. Amongst the RVers and period-costume-wearing tourist office employees, the paddlers are easy to spot. Fascinating is the change in the faces of competitors we met just three days prior—everyone’s aged. Eyes sunk, cheekbones protrude and fine lines amass.

Everyone sleeps.

At the banquet the following day we discover a race beyond our own limited perspective. A tandem kayak won in 44 hours and 51 minutes; a tandem canoe hot on their stern finished just 42 minutes later.

How did teams speed to Dawson a full 25 hours before us? There’s a mix of strategies we learn, including the high-tech, such as GPS units used to find the fastest current, and the dedicated—some wore condom catheters. Then there was common sense. “You don’t get out of your boat, except for Carmacks and Kirkman Creek,” advises Gaetan Plourde, one half of the winning tandem canoe team. Marathon canoeing experience helps.

When I ask who plans to return next year I get a variety of responses. Some can’t wait, others tell me the race was psychological torture, and swear never to come back.

“No one else will understand what we went through unless they’ve also done it,” kayaker Patrick Novak tells me. We’re standing in the Downtown Hotel bar, watching our comrades shoot back Dawson’s infamous Sour Toe Cocktail—a shot of liquor with a preserved human toe added as garnish. I agree.

The emotional roller coaster the race provides is fascinating and devastating. In the past 72 hours, we’ve all glimpsed ourselves at our strongest and weakest—it’s not an experience anyone forgets. And it might be a little addicting.

“Let’s do it again next year,” Geoff suggests as we walk back to our cabin under a sleepless sun.

“Or how about with a voyageur team—wouldn’t that be fun?” I ask. Though we’re in enthusiastic agreement, it’ll be another four days before the tingling in my hands goes away and Geoff can raise his arms above his head.

Why do it? The same reason people have always gone to Dawson—the promise of adventure, glory and gold.

Kaydi Pyette is the editor of Canoeroots.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.