It’s just an ordinary beaver lodge—a dome-shaped mass of sticks plastered with mud. It’s situated on a small pond, halfway down the Wakimika River in northern Ontario’s famed Temagami wilderness. Five of us, floating in three canoes, gather round with cameras at the ready, hoping for a shot. Here, in the oldest stand of red and white pine in the world, we’re searching for an echo.

My husband, Gary, and I are guiding a very special trip. Accompanying us is a small crew creating a film exploring the beginnings of Canada’s most famous and controversial conservationist.

During the early 20th century, Grey Owl helped to save the industrious beaver from the edge of extinction, becoming a bestselling author in the process. He wrote five books, dozens of articles, starred in National Film Board movies and gave hundreds of lectures. Shortly after his death he was exposed as a Brit pretending to be a First Nations man.

More than 75 years later, we’re paddling into the network of wilderness waterways he called home, following in the footsteps of this complex conservation giant to discover his beginnings.

Though Grey Owl is often associated with his final resting place in Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan, it was his years near canoe- culture mecca Temagami, where he learned bushcraft skills from seasoned trappers, guides and Ojibway elders.

MAKING A MARK ON HISTORY

It’s a sunny July afternoon three days before we depart for the wilderness when I meet our group at the Temagami Canoe Festival. Water laps against the docks, boats come and go from the marina, music and traditional drumming emanate from the stage. People surround a birchbark canoe admiring the builder’s handiwork. The owner of the Temagami Canoe Company, the second oldest canoe manufacturer in the nation, offers demonstrations of traditional cedar canvas boat building techniques.

It’s here I meet the man who will narrate our film: BBC personality Ray Mears is famous for his Ray Mears’ Bushcraft and Ray Mears Goes Walkabout TV shows, as well as a for being a bushcraft expert. He’s also a Grey Owl admirer. Ray is here demonstrating his wilderness techniques for festival goers.

An enthusiast of Grey Owl’s writing and work, Ray has long dreamed of exploring the Temagami area that shaped Grey Owl. Though separated by decades, the two grew up in neighboring rural towns in the United Kingdom.

Their differences are vast, but it’s hard to ignore similarities between the two wilderness philosophers. There’s a shared appreciation of the traditional ways of the First Nations and both have passionately championed conservation.

“He grew up with nature on his doorstep; it just wasn’t big enough for him. I can relate to that,” says Ray.

The following afternoon Gary and I travel with our three companions, including videographer, Goh Iromoto, and Oliver Thring, a writer from the Sunday Times in London, to Bear Island on Lake Temagami. There’s no better place to begin Grey Owl’s story than right here. Our host, Virginia Mckenzie of the Teme-Augama First Nation, shares stories of when Grey Owl met her grandfather here in the summer of 1907.

Back then Grey Owl was a 19-year-old British immigrant by the name of Archibald Belaney.

Archie’s first trip to Bear Island involved a rigorous canoe trip from Temiskaming with his mentor, Bill Guppy, an experienced guide and trapper. It was a steep learning curve involving all aspects of canoe travel. Whitewater paddling, upstream poling and strenuous portaging—Archie learned it all.

As they journeyed from their winter trapping grounds in Quebec to the summer guiding opportunities on Lake Temagami, Archie passed the even more important test of maintaining perseverance, a positive outlook and a constant willingness to master skills in the face of exhaustion. He fell in love with the ways of the First Nations people—a way of life that was becoming increasingly fragile with industrialization.

Today, Virginia focuses on reviving her people’s culture through traditions and ceremonies that had at one time all but disappeared. As the community librarian, she proudly shows off a collection of photo albums and newspaper clippings depicting the early 20th century on Bear Island, including a lovely portrait of Grey Owl’s first wife, Angele.

“[Grey Owl] made a mark on history, he’s made a mark on the area, he’s made a mark all over the world,” says Virginia. That his story begins here is a source of pride.

AN IMPORTANT VOICE FOR THE COMMUNITY

That night, at Smoothwater Wilderness Outfitters Ecolodge (smoothwater.com), we look over maps.

Gary has laid out a route that Grey Owl would’ve paddled often. The Wakimika River offers a good chance of seeing beavers, as well as sites with significant spiritual, historical and ecological significance.

Although the topographic map indicates we’ll be paddling through Obabika River Provincial Park near the Lady Evelyn-Smoothwater Wilderness, we know this to be the traditional lands of the Misabi family. We hope to meet with Misabi Elder, Alex Mathias, who lives in a cabin near our route. Gary and I first met Alex on a canoe trip 18 years ago while on a personal quest to help save Ontario’s old growth.

Our daughter took her first steps at his camp three years later. Alex remains an important voice for his community and the wild, in ways similar to Grey Owl.

We leave the town of Temagami via de Havilland Beavers with a roar of engines. Grey Owl never saw the landscape from this perspective—I imagine the grandest views he ever had of the vast pine forests and the countless islands stretching out beneath us were from the fire towers on Maple Mountain, Caribou Mountain, Ishpatina Ridge and Obabika Lake.

The pilot brings the Beaver in a wide arc north of Obabika Lake over what is known by canoeists as the Wakimika Triangle. Of all Temagami’s vast network of interconnected nastawgan, this is one of the most beloved canoe routes. From our eye perspective, we can see the lakes and rivers of our entire route surrounded by the greatest red and white old growth pine forest in the world. The sky is dark and threatening rain when we suddenly swoop down over the treetops and the pontoons touch down on Wakimika Lake.

A SPECIES IN NEED OF A CHAMPION

A torrential downpour at first light makes me thankful Gary had rigged a large tarp over the kitchen area the night before. It passes quickly and soon everyone is out of the tents to film and photograph in the morning light. By the time I have hot cereal on and the smell of coffee wafts through the campsite, the west wind completely clears the skies.

We set off down the lake with the wind to our backs and enter the Wakimika River at Grassy Bay. A full day lies ahead as we meander to Obabika.

“Traveling down that river, knowing that he’d been here, is very special,” Ray says later. “I feel like I’m paddling in his wake.” Having spent three months in the summer of 1997 exploring this area by canoe and tracing Grey Owl’s explorations, the echo of his presence is a feeling I can relate to.

The river widens into a pond surrounded by cedar and black spruce. A channel through riverside grasses leads us to a beaver lodge. Somewhere beneath us is the underwater entrance to their snug abode. We sit quietly, paddles resting across the gunwales, hoping to catch a glimpse.

The beavers are a constant source of conversation for the group. During the fur trade years, beaver pelts were the most valuable natural resource in Canada. Their luxurious fur drove trade across the continent for two centuries, motivating much of the early exploration of North America. At its height, indiscriminate trapping sent 100,000 beaver pelts back to Europe every year.

In the way that it must have seemed inconceivable that such an abundant bird as the passenger pigeon would go extinct, so too was the story with the ubiquitous beaver. A flood of get-rich-quick entrepreneurs almost trapped the beaver into oblivion by the mid-1920s. The species was in need of a champion.

CONSERVATION THROUGH STORYTELLING

By the mid-1920s, Archie had long since adopted the identity of Grey Owl, claiming to be born to a Scottish father and Apache mother. He ran a trapline with an Iroquois girl, Gertrude. One spring, with the beaver all but gone, Archie unintentionally trapped a female. Feeling guilty, he rescued her pair of surviving kits, and named them McGinnis and McGinty. These two beavers and the two that followed, Jelly Roll and Rawhide, got up to all sorts of antics in Grey Owl’s life, including building a lodge inside his cabin.

Their endearing personalities became the catalyst for much of Grey Owl’s conservation ethic and decision to quit trapping. His first-hand descriptions of living with the beavers and other wilderness adventures enthralled people around the world. He was even invited to meet King George VI and the royal princesses when he visited Britain on a book tour. His ethos that the wilderness is more than a resource to be plundered was a new idea for many at the time.

Through his storytelling, “He made people aware of the plight of the beaver and was very significant in changing attitudes,” says Ray. “The work he did was incredibly important.”

Grey Owl’s true identity was exposed soon after his death in 1938. “I don’t think the world really knows how to talk about Grey Owl,” says Ray. “In one sense they’re moved by his success, yet, at the same time, commentators have to explain he wasn’t a First Nation person and ask whether he was a fraud.”

“I don’t think of him in those terms,” Ray continues. “What’s important are not the personal demons he brought with him, but his message of conservation, which was ahead of its time. It’s as important today as it ever was.”

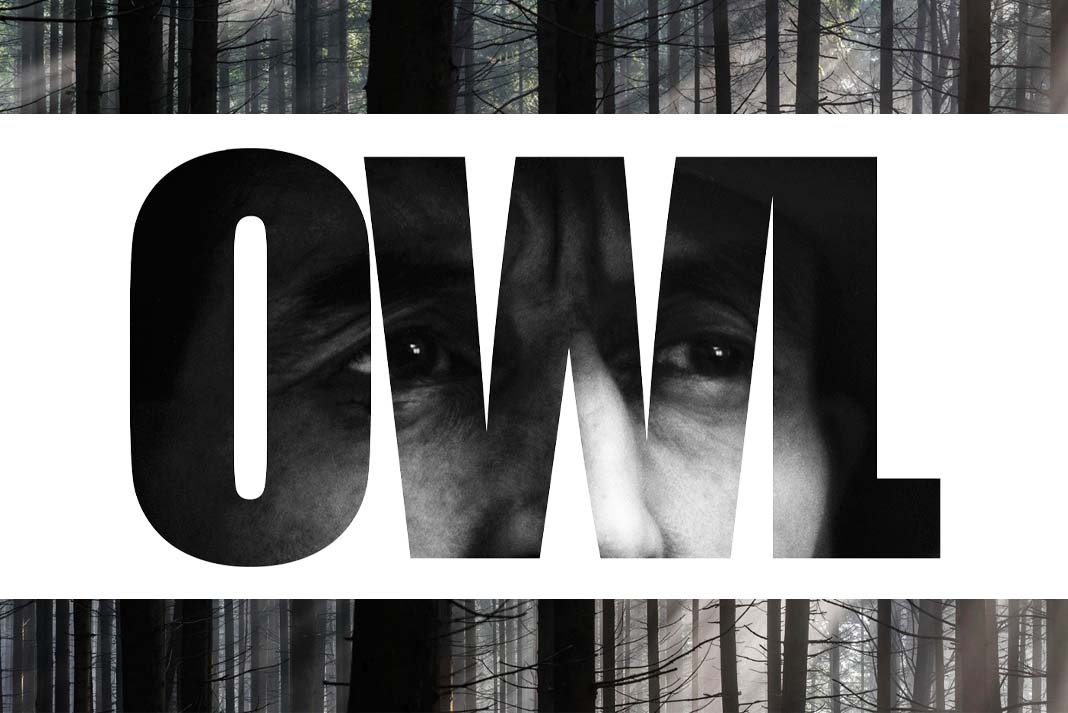

PHOTO: GARY MCGUFFIN

WALKING IN GREY OWL’S FOOTSTEPS

Temagami has a history of making conservationists.

At the north end of Obabika Lake, we reach the infamous place where two huge rock-filled cribs flank the river. A logging road built here in the ‘80s was part of a plan to log the 300-year-old old growth forest.

Though it’s almost three decades later, no one has forgotten the bitter fight between the 300 protesters arrested and those who wanted the timber. As we paddle by, only the sounds of nature preside: A red squirrel’s scolding, the swish of our paddles and the rush of water flowing through the half- finished beaver dam spanning the stretch where the road once stood.

That night we pitch our tents beneath the pines. Two loons surface nearby, calling to one another. Around the campfire, under star-speckled skies, we plan the next day’s travels.

From the beach landing, the trail climbs straight up into the forest. With the canoe over my head, I focus on my footing. The forest floor is covered in a thick layer of pine needles. Tendrils of wintergreen and golden thread weave across the ground. Every so often I see small clumps of translucent white Indian pipes poking up through thick mats of sphagnum moss. Small birches, balsam and ferns line the path. Huge tree roots snaking across the path create a natural staircase up the steep parts. However, it’s the gigantic trunks of the ancient pine giving me the sensation I’m an ant beside an elephant that I love most about this trail.

Written in that deeply furrowed bark is a history as old as the Hudson’s Bay Company. These giants have seen the wanderings of nomadic people, the Europeans come and go and even Grey Owl himself.

I drop the canoe at a trail junction to signify to the others the proper route to follow to the lake. Returning for my pack, I meet Ray carrying the cedarstrip with ease. Not far behind is the crew’s writer, Oliver, red-faced, sweating and straining every muscle. It’s his very first portage. When I offer assistance, he declines with a grin. “I feel at last that I am really walking in Grey Owl’s footsteps,” Oliver tells me.

As we approach Kokomis-Shomis, the Grandparent Rocks, the cliff is in shade. The red ochre figures are faded but easy to spot on the east side of Lake Obabika. We speculate about what the long-ago artist was thinking. Of the paintings’ symbolic meaning, we can only surmise. I leave tobacco.

We beach the canoes at Fire Ranger Point, named for a long-gone wooden fire tower that once overlooked the lake. It is a beautiful spot with views in all directions. Near the lake where we camp, a circle of small stones marks the fire ring everyone uses. Ray takes the few dead branches we’ve collected and places them in a star shape.

Three longer pieces are joined to form a tripod, which he centers over the fireplace. Then he selects a birch branch and deftly slices it off with his knife. He twists and twists until it forms a hook onto which he hangs his kettle, which is suspended from the tripod.

“It’s more efficient, safer, cleaner and you use a lot less wood,” Ray says of the technique.

In just a few short days with Ray, I’ve become a believer that teaching traditional bushcraft skills would go a long way to preserving campsites, conserving firewood, preventing forest fires and instilling a great deal more respect for the land. This is real no-trace camping.

On this final evening of our trip, Misabi Elder Alex Mathias pays a visit. He is wearing his traditional Anishinabe costume; a leather fringed coat with beadwork and an elaborate red and white headdress of eagle feathers. It’s wonderful to see my old friend. He and Ray get along famously.

Alex has brought old photographs and a fresh-caught lake trout to share, and he regales us with stories of his early life living on the land and traveling by canoe and dogsled, before his family moved to Bear Island.

Our small group speaks of the beavers, ancient pines and Temagami’s nastawgan. Alex’s visit is a reminder of all that could have been lost and all that has been saved by conservationists like Grey Owl.

“Grey Owl put his message out into the world, but to my mind he also handed out responsibility to the future,” says Ray. The day before, Ray had drawn out a dog-eared original of Grey Owl’s 1937 book, The Tree, and thumbed to a favorite passage.

“And the mountains looked on in stony calmness; for they knew that trees must die and so must men, but that they live on forever.”

“The message is simple,” concludes Ray. “Despite us, the land will survive. We have the choice to live in beauty or not. And that’s still the case today.”

Joanie McGuffin is the co-author of In The Footsteps of Grey Owl, a conservationist and explorer. Find her current projects at themcguffins.ca.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.