Canada’s favorite canoe wears many faces. It’s been that way since the beginning, when the Chestnut Canoe Company debuted the Prospector model canoes in response to demands from rockhounds of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). That was in 1923, and the Fredericton, New Brunswick-based wood-canvas canoe manufacturer was rebuilding from a devastating fire the year before.

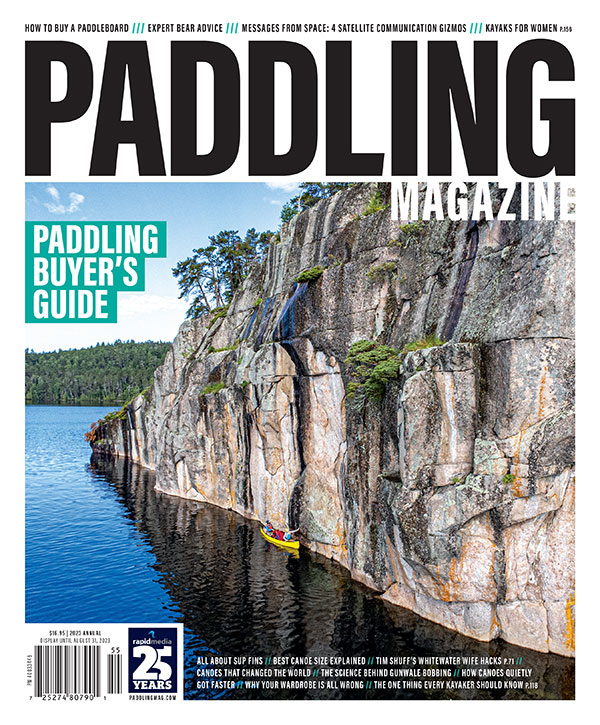

Magical strokes: Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Prospector canoe

A profile of the Prospector canoe design would be far simpler if its origins were tied to one builder. While the design likely originated in New Brunswick, Chestnut cannot claim sole ownership. For close to four decades, Chestnut, the Peterborough Canoe Company and the Canadian Canoe Company shared an identical lineup of canoes, including Prospectors in various lengths. Based on the original wood-canvas Prospectors remaining in service, it’s clear the Chestnut decal was most common. Such a tangled genealogy sets the stage for what remains a complicated history of an iconic canoe.

Developing the “ultimate all-around canoe”

Like so many personalities in Canada’s past, the Prospector was born out of the colonization of the northern frontier. Before the advent of bush planes, the GSC was Chestnut’s biggest customer. Its “canoemen” complained the cottage-grade Pleasure canoes of the day didn’t have nearly enough capacity for the heavy loads of geological exploration. At the same time, oversized Freighter canoes were too cumbersome to paddle and portage. Wilderness journeys and claim staking demanded high-volume and seaworthy canoes that performed well in whitewater and on windswept lakes.

As a stopgap measure, Chestnut and its sister companies had offered up to three inches of additional depth in the sleek Cruiser models which early builders had copied from local Indigenous birchbark canoes and early wood-canvas models from Maine. The Prospector, claimed Chestnut’s 1925 catalog, “embodies the good points of both our Cruiser and Pleasure model and is sure to please anyone looking for a light canoe of large carrying capacity.”

Chestnut initially offered 15-, 16-, 17- and 18-footers in 1923; 12- and 14-foot models came a few years later. Most were also made in Y-stern configurations to accept an outboard motor. Each model had unique proportions and personalities on the water that went beyond differences in length. For all the praise today’s bestselling 16-foot Prospector receives from modern paddlers, including Bill Mason and Kevin Callan, as the “ultimate all-around canoe,” it was less popular than the hulking 18-footer in the early days.

The shape of wood-canvas Prospectors evolved slightly over time as builders’ forms deteriorated and were modified or replaced. The Peterborough version, which went out of production when the company folded in 1961, was sleeker in the stems and less rockered than the Chestnut. Historian Dan Miller’s website, The Wooden Canoe Museum, tracks the changes over time, revealed in fractions of inches in beam and depth. More noticeable is the inflation of price: a 16-foot Chestnut Prospector went from $77 in 1925 to $624 in 1976.

Prospectors paddle into the modern era

Mason lamented the end of the Chestnut Prospector when the company went bankrupt in 1979. Yet Mason’s lavish praise ushered the design into the modern era, and now just about every contemporary builder makes a Prospector. London, Ontario-based Nova Craft Canoe was among the first, developing a composite replica in 1984. Ottawa’s Trailhead Canoes took measurements from Mason’s Chestnut original for its fiberglass, aramid and plastic clones.

For better or worse, limitations in molding and economies of scale encouraged most modern manufacturers to stray from the subtle differences between the Prospector models. For example, Nova Craft’s Prospectors have the exact same width, depth and rocker across 15-, 16-, 17- and 18-foot lengths. Today, the canoe is best defined as a general category of wilderness tripper with above-average depth, width and rocker.

For a true Prospector, you have to go back to wood-canvas. Only one original Chestnut form remains in commercial service today. Wakefield, Quebec-based builder Headwaters Canoes still makes one or two 18-foot Prospectors per year, ordered by hard-core traditionalists. The century-old Chestnut form shows its age, and Headwaters’ builders Kate Prince and Jamie Bartle must carefully align inner gunwales and stems to assure a symmetrical canoe before bending steam-bent cedar ribs over the weathered mold.

The result after over 100 hours of manual labor is a beautiful canoe whose graceful performance in wind, waves and rapids with an expedition load belies its behemoth dimensions and 90-pound heft. The Prospector, as Chestnut historian Roger MacGregor notes, is “one of these magical strokes, a judicious combination of the finest shapes at just the right spot along the hull.”

Conor Mihell’s first Rapid Media article appeared in the 2005 Buyer’s Guide issue of Canoeroots.

Esquif is another brand carrying forward the Prospector tradition, producing contemporary 15-, 16- and 17-foot lengths. What the GSC canoemen would have given for a T-Formex version of their 18-footer. | Feature photo: Brad Jennings

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.