The paddling community judges accidents harshly. We are so determined to figure it out and ascribe a cause to the incident we often rush to conclusions before all the facts are available and blame the victims in the process. Instead, we ought to humbly reflect on what lessons the incident can teach us and give thanks for surviving our own near misses.

When a paddler dies, we are too quick to judge

To be sure, analyzing, debriefing and accident reviews are essential to lifesaving takeaways. Accidents are too common and need to be reduced. According to United States Coast Guard (USCG) data, there were 183 paddling deaths in the U.S. in 2023. Kayaks were the second most common type of vessel involved in fatalities, second only to open motorboats.

Even as I sat down to write this, reports came in of two separate kayaking accidents that killed three people in one windy afternoon in British Columbia. On Saturday, April 20, two young men flipped in a tandem kayak in waves and tidal currents near Victoria. Their kayak and bodies washed ashore separately in the nearby San Juan Islands. Later the same day, a father and son in another tandem kayak flipped in Deep Cove, a popular kayaking spot near Vancouver. They were rescued, but the 70-year-old father didn’t survive. Early reports, which can often be wrong, suggest none of the victims were dressed for immersion.

Predictably, the online comments rolled in. First came the ill-informed armchair experts, pompous pronouncers of the obvious who bestow Darwin Awards and claim they wouldn’t have made the same mistakes. They are the first to speak up because what they say requires the least thought.

“Why would they be so far off land in a kayak in the ocean in the first place?” suggested one commenter about the first incident. From another: “This area is subject to the Venturi Effect. Consequently, currents can be quite strong and are influenced by various factors, including tides, winds and the topography of the sea floor.”

Okay, Einstein.

Or how about this one: “When a mistake is made in the ocean, it can be an unforgiving place.”

Thanks, Captain Obvious.

More knowledgeable commentary emerges later. However, some self-appointed experts parse the details and act as if the mastication of the event’s minutiae by their incisive intellectual chops can nullify all likelihood of any such tragedy occurring in the future. If only we would all keep cool heads and just look at the facts, our safety would be guaranteed. Simply venture forth protected by perfect knowledge, perfect judgment and an armor of radios, flares, satellite communicators, Gore-Tex, and leashes of the appropriate length and material to stay attached to all of it, in all conditions.

Too often, this is accompanied by an unspoken it-couldn’t-have-been-me subtext. We cling to every discerning detail—the victims had the wrong kind of kayak, a lack of certain safety equipment, insufficient training, or a bad weather forecast—anything to separate them from us.

That wouldn’t have happened to a real sea kayaker.

“The truth is, we are all vulnerable. The judgment we are too keen to apply to other people’s paddling accidents is an unhealthy coping tool, a way to avoid facing this truth.”

There is some truth to such distinctions. According to the same USCG data, three-quarters of paddlesports deaths are people with less than 100 hours of experience. And over 80 percent of people who drown in boating accidents weren’t wearing PFDs. But these stats probably say less about how dangerous it is to be a beginner and more about how many beginners there are. It’s like the statistic stating most people die near where they live. It doesn’t mean you’re safe if you never go home. Similarly, having a kayak with bulkheads and wearing a PFD doesn’t make you immortal.

Down to a coin flip

The movie Beyond the Salish, which won best sea kayaking film in this year’s Paddling Film Festival, shows how easily things can go wrong even for those who think they’re well-prepared. It tells the story of two enthusiastic young kayakers, Richard Chen and William Chong, who are rescued by helicopter after a harrowing capsize on the outer coast of Vancouver Island.

The pair had practiced rescues and wore wetsuits, paddling jackets and quality PFDs. But the movie will attract commentary from the same backseat critics who vulture around every kayaking accident: They were stupid and should have known better. Richard says as much himself.

Survey Says

We asked our readers about safety habits. Here’s what you had to say.

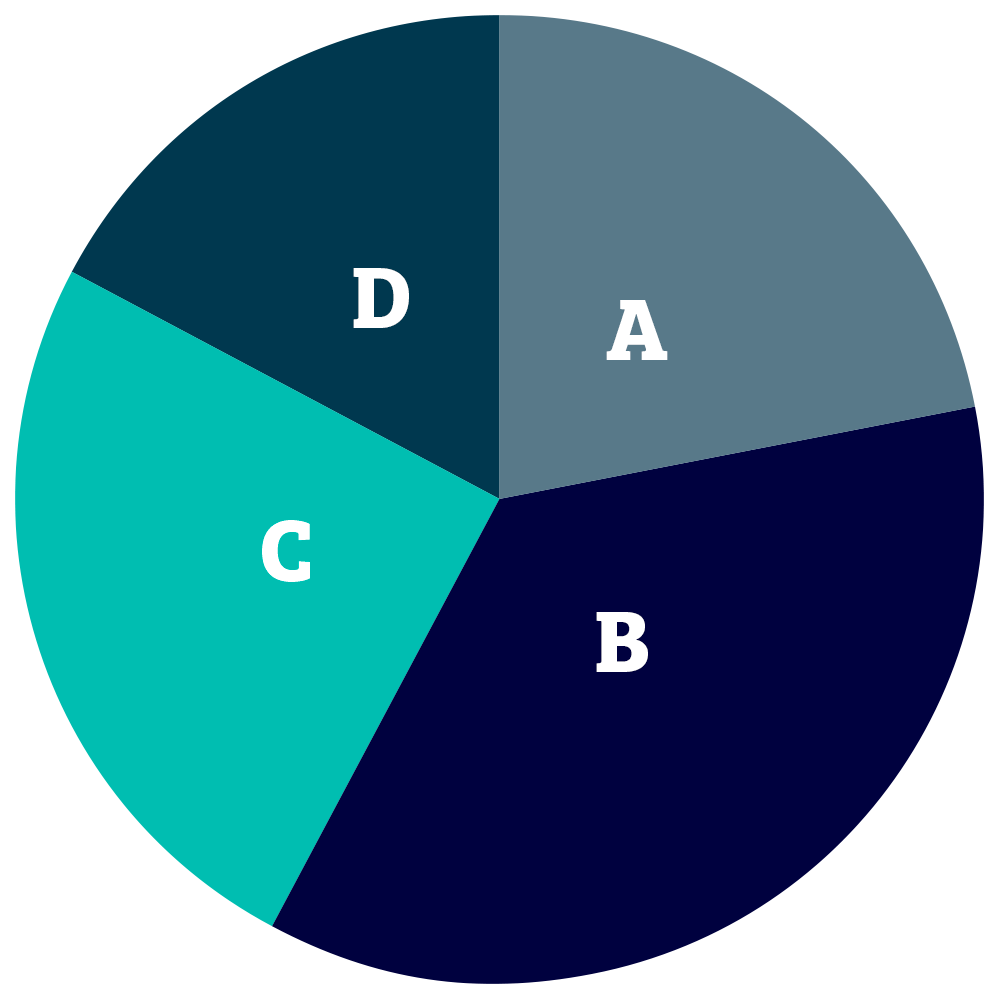

How often do you paddle alone?

A: All the time — 22%

B: Most of the time — 36%

C: Rarely — 25%

D: Never — 17%

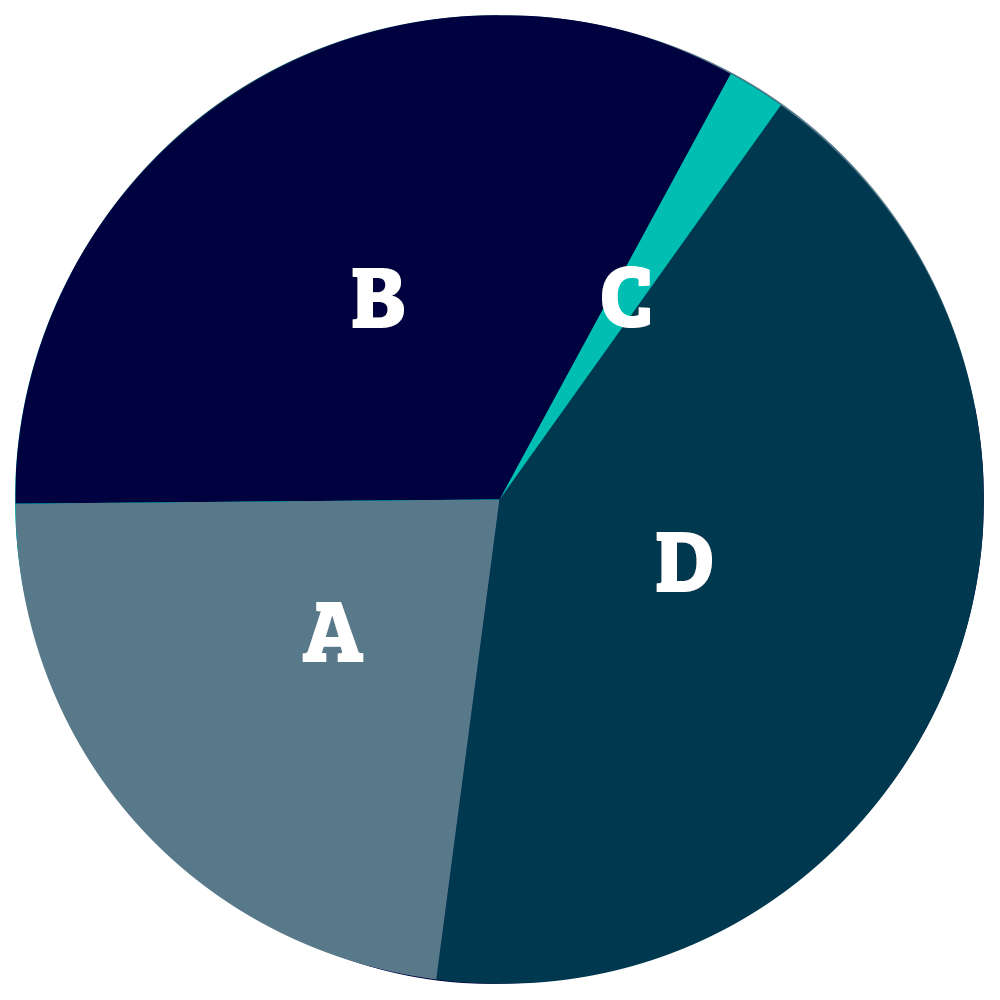

When paddling, which do you always carry?

A: Signaling device (whistle or strobe) — 23%

B: Cell phone in a waterproof bag or case — 33%

C: Handheld VHF radio — 2%

D: A combination of these devices — 42%

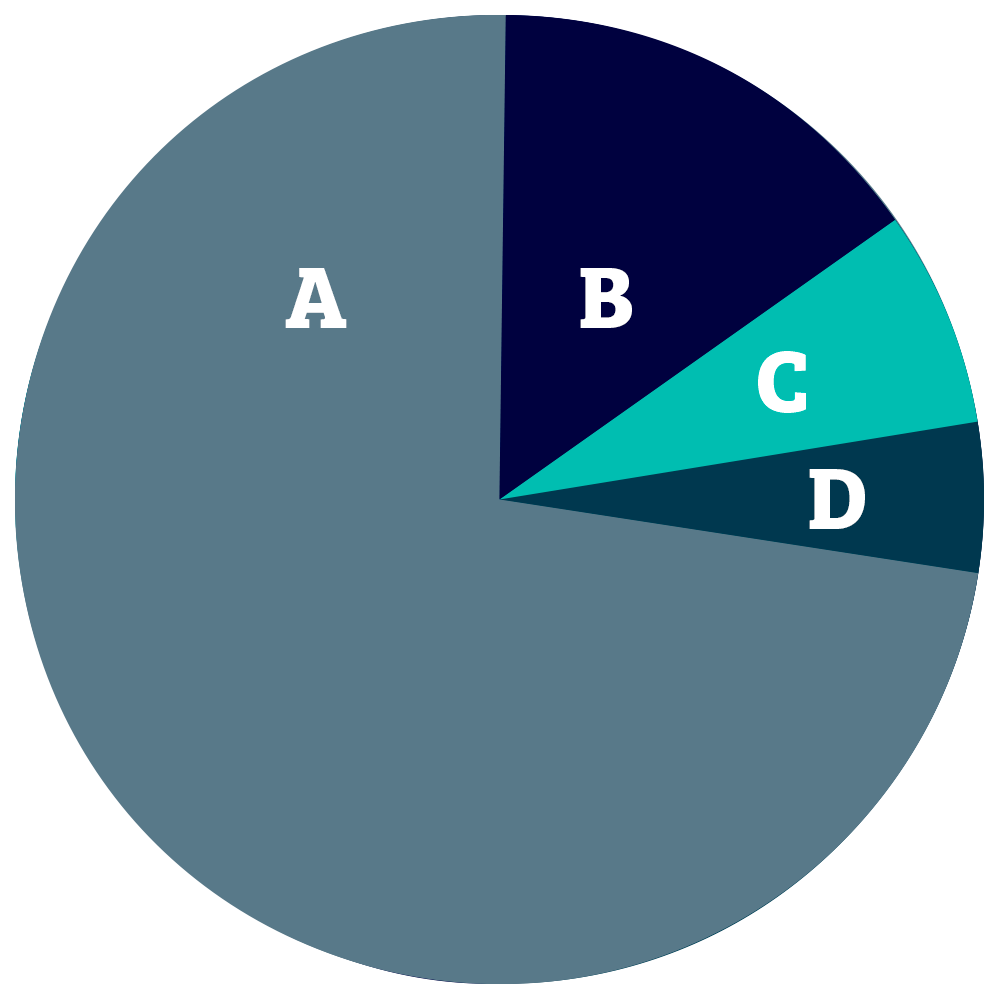

Do you check weather or river gauges before paddling?

A: Always — 73%

B: Frequently — 15%

C: Occasionally — 7%

D: Never — 5%

Well, this is a surprise. More than half of our poll respondents say they paddle alone most or all of the time. That goes against the prime directive we paddlers have heard from summer camp straight up to today—never paddle alone. According to our survey, only 17 percent of paddlers stick to that golden rule all the time, while 25 percent admit to paddling alone on rare occasions.

There are different degrees of paddling alone, of course. If you go to a popular paddling area by yourself, you could be alone but not entirely on your own. After all, another cardinal rule of our sport is to always help a paddler in need—strangers included.

Readers do better when it comes to carrying signaling devices and phones with them on the water. Still, if you need help, it’s a lot easier to holler at the paddling buddy next to you than to phone a friend in the next county.

My friend Dave and I paddled the same stretch of coastline when we were about the same age. In hindsight, I tend to think our survival is evidence of superior skill and judgment. I wouldn’t have let go of my paddle and lost my balance like Richard, right? But I need look no further than my journals to see how much of our safety was dumb luck.

There was the time we found ourselves panicking in huge seas offshore of the Cape Beale Lighthouse. In my memory, we’d headed out into calm weather and been surprised by the conditions. But my journal tells a different story. The forecast had been for a 13-foot swell.

“This could be a crazy day,” I’d told Dave. But, brimming with confidence from hundreds of miles of safe paddling, often with threatening forecasts that had turned out to be fine, our motto had become, “paddle anyway, change plans later.”

“If we get pummeled, we get pummeled,” Dave announced, responding to my concern about what 13-foot swell might mean for a surf landing. Once we got a half-mile offshore, our confidence dissolved.

“Now I’m scared,” Dave yelled over the wavetops. We shakily turned around, bracing against the whitecaps, and surfed into safety behind the lighthouse.

“So you’re the kayakers giving me more grey hairs this morning,” the lightkeeper greeted us. He’d had his binoculars trained on us the whole time, ready to call the coast guard.

I can count half a dozen other close calls with no help nearby.

“I thought we were elite kayakers, but now I see we just had good weather,” I wrote in my journal. “The feeling of power is gone, replaced by a reverence, gratitude, humility.” Over time, humility was replaced by complacency and pride.

The only thing separating us from Richard and William is we didn’t capsize. Maybe we were stronger paddlers, or perhaps it was because we had the good judgment to turn around. But at the time, the decision felt like a coin flip. There’s probably some alternate universe where those two young men finish their trip safely, and Dave and I are airlifted out. Our good fortune is not a qualification for grandstanding.

What the water teaches

The truth is, we are all vulnerable. The judgment we are too keen to apply to other people’s paddling accidents is an unhealthy coping tool, a way to avoid facing this truth. In her memoir, No Cure for Being Human, the religious scholar and cancer survivor Kate Bowler explains this tendency we have to recoil from the tragedy in others’ lives. “Who wants to be confronted with the reality that we are all a breath away from a problem that could alter our lives completely?” she writes.

To learn from others’ mistakes and misfortune, we have to first accept it could have been us. Less judgment, less opining, more openness and empathy. This is what the water teaches us, after all, if we are willing to listen.

Tim Shuff is a sea kayaker, firefighter and former editor of Adventure Kayak magazine.

Friendly swell or time to get off the water? It depends on who you ask. | Feature photo: David Jackson

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was first published in Issue 72 of Paddling Magazine.

I wrote this a few years ago. Similar message.

https://silentsportsmagazine.com/2016/02/05/get-over-the-not-me-not-today-syndrome/