Uncharted rivers are few and far between in 2016. There’s a tribe who seek their fruits for various reasons, often leading them to the most remote stretches of wilderness on earth. The Nelson River, tucked in the wilds of northern Manitoba, is no exception.

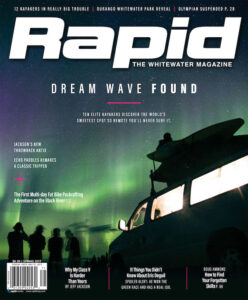

Catching the dream wave on northern Manitoba’s Nelson River

Joel Kowalski had been staring at the Nelson River on Google Earth for more than four years. From what he could tell from the satellite images, Canada’s fourth largest river looked like an oversized version of the Ottawa. For Kowalski, who grew up on the banks of the Ottawa River, the Nelson was everything an elite freestyle kayaker could ask for. Except maybe easy access.

“The Nelson isn’t like a river draining a big basin, it’s more like a river draining an inland ocean,” he noted prior to departure. “There are a few qualities that make a place have a lot of really good surf waves, but this seemed to be on a scale we hadn’t experienced yet.”

From the satellite images, Kowalski could tell this was a very high-flow river with low-gradient. Also appealing was the Nelson’s many parallel channels separated by long sections of flat water, which would allow the team to motor downriver in two 20-foot rafts and have multiple options to pick their way through drops.

The road to Cross Lake

On September 6, 10 paddlers set out from the Ottawa Valley on a 40-hour drive northwest. Kowalski had compiled a team of elite competition, freestyle and racing kayakers to seek out the Nelson River. The team included Ben Marr, Dane Jackson and Bren Orton. A passenger van, borrowed from the Kowalski family business, rafting operator Wilderness Tours, towed a colorful trailer full of expedition gear and freestyle kayaks.

The team made the continuous drive and arrived under the northern lights in Cross Lake at 2 a.m. Located 771 kilometers north of the provincial capital of Winnipeg, the tiny town is home to just 338 residents. Half of the boys pitched on a modest motel room; the others curled up under transport trailer beds only to be awoken in the wee hours of the morning by a roaming black bear.

Blue skies that day were a fortuitous sign for Kowalski and Marr, who met their floatplane pilot lakeside, ready for a reconnaissance flight over the section of the river in question.

“These flights can do a few things. It will either answer our questions or give us a lot more,” Marr said before the flight.

While calm and collected at first, elation set in when Kowalski and Marr laid eyes on the rapid they had been calling Powerline. Spotting a shoulder on the edge of an enormous hole, Marr shifted and straightened to get a better look. Could it be? The two met with wide eyes before peering once again out the bubble window of the de Havilland Beaver. The pilot did three slow closer passes, circling and dropping lower each time.

“Things were starting to take shape—we were looking at what we had been dreaming of,” says Kowalski. There was so much water flowing, beyond anything they had expected.

“We were thinking both the same thing, but we didn’t want to say anything to the other guys—it’s easy to get too excited and make judgments too early,” says Kowalski, who admits he played it pretty low-key afterwards. By the time the plane landed Marr and Kowalski were stoic again, childlike Christmas morning excitement put aside.

Setting out for the Nelson River

Back in Cross Lake, the rest of the group had attracted a curious and increasingly concerned entourage as they were packing the rafts. Locals voiced heavy skepticism. Many thought this was a death mission, as the wild river had taken many local lives in years past. The team was invited to a send-off feast by the local Pimicikamak Nation where they dined with the council on moose, fresh-baked bannock and walleye.

“Half the town was excited; the other half were sure they were never going to see us again.”

Offered safe passage by the council, the team departed the next morning with local flags waving under cloudy skies.

“Half the town was excited; the other half were sure they were never going to see us again,” says Kowalski.

The river quickly took on a prehistoric feel. White pelicans flew overhead, eagles screamed as they dove for fish and not a single other soul was seen.

The first evening out they came to the first rapid. “It was so much bigger than either Benny or I had thought from the air. It was the same size as Hermit on the Grand Canyon. That really surprised us,” says Kowalski.

Still, it wasn’t until the fourth day of the trip that the team arrived at what they had been calling Powerline—and what the locals referred to as Bladder Rapids—uncovering what would be aptly renamed, Dream Wave.

Dream Wave found

“As we got closer, we were starting to get anxious, bordering on nervous, because when we were still about three kilometers from the start of the rapid we could see massive explosions of water bursting over the horizon line,” says Kowalski.

When the group pulled off river right to scout, the team was stunned by the size of the gigantic hole and massive wave. “Half of the team wanted to drop everything and just start surfing right then and there, but we set up camp first,” says Kowalski.

“We could see massive explosions of water bursting over the horizon line.”

Once a main shelter was established the team started kayaking. For the next six nights, time disappeared in Northern Manitoba and the greatest river wave ever surfed was in session. For Kowalski, it was the culmination of four years of dreaming, 40 hours of driving and four days of searching.

“It was the combination of everything you could want out of a surf wave. It was really tall, really wide, really fun and surfable left to right—even if you weren’t throwing tricks you’d have fun,” says Kowalski. “Easy and smooth to surf. As easy as Pushbutton on the Ottawa, but huge.”

The team lived in a kind of Never Neverland. Always in earshot of the roar of the river and surrounded by black spruce and jack pine, they were united by all-day surf sessions and only interrupted by fishing, shooting guns, making fire and food. The rafts had carried in a generator with gasoline, propane cook stoves and five coolers of food. “We didn’t pack light—it was as cushy as you could get considering where we went,” says Kowalski.

Returning from a world-class run

After enjoying 10 days on the river it was a full day to motor out and meet the shuttle.

A welcoming crowd greeted the team at the take-out. Back in town the kayakers were revered, and again hosted at an amazing feast. Kowalski put together a short presentation with videos and photos for the chief and local councils to showcase the expedition. In turn, the hosts shared their own experiences on the river.

“The locals travel the river to fish for sturgeon and hunt. They’ll bring tin boats to the edge of the rapids then portage with a winch system. But many people have drowned or simply disappeared,” says Kowalski.

“Yet, in light of what we were telling them, they were very excited,” he adds. “None of them had considered they were sitting on top of some of the best whitewater in the world.”

Kowalski plans to return next summer for a second mission to Dream Wave.

David Jackson is an award-winning photojournalist with a penchant for paddling adventures. When he’s not on assignment, he calls the Ottawa Valley his home.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Rapid. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Rapid. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.Ben Marr surfing on Manitoba’s Nelson River. | Feature photo: David Jackson