On the second Thursday in March last year, workers hustled to assemble exhibits, rack hundreds of kayaks, canoes and paddleboards, and arrange bales of gear inside the Alliant Energy Center in Madison. In just over 24 hours, the Wisconsin venue would play host to the world’s largest consumer paddling show, Canoecopia. Part exhibition, part tradeshow and part Black Friday for boaters, Canoecopia marks the unofficial opening day of the Midwest paddling season—a time to hunt bargains and stoke dreams. This year, however, the festive mood was tinged with uncertainty.

COVID-19 had gained a foothold in North America, and what had been a distant curiosity in February took on a new sense of manic menace in March. Americans looked on as the disease jumped from China’s Wuhan province to other parts of Asia, then spread to Iran and exploded across Italy, overwhelming hospitals there. We watched on social media as locked-down apartment dwellers serenaded their neighbors with accordion folk tunes.

One of those watching closely was Canoecopia organizer Darren Bush, the owner of Madison’s Rutabaga Paddlesports who, years ago, had worked as a data scientist for the Wisconsin State Department of Health. He’d seen the surging COVID-19 case numbers and knew what they meant. Bush had sunk tens of thousands of dollars into the show, which is also the biggest sales weekend of the year for Rutabaga. He knew canceling Canoecopia at the last minute could well mean the end of his business, but the alternative was unthinkable.

“If we have to liquidate and go bankrupt, then we liquidate and go bankrupt,” Bush told his wife. “But I’m not killing a bunch of people.”

Canoecopia was off.

When Bush made the announcement to a few dozen industry veterans, they broke into applause. A few hugged Bush—the distancing protocols hadn’t yet become habit—and then immediately set about grappling with existential questions of their own. No one knew quite what to make of the novel coronavirus, but it would bring the paddling business to a screeching halt at the worst possible time.

The early days

In the emptying corridors of Canoecopia, industry stalwarts wondered if their companies could survive the shutdown, and if not, whether the sport they’d built their lives around would ever be the same. Lili Colby, co-owner with her husband, Gordon, of life jacket company MTI Adventurewear, decompressed with a cocktail while changing planes on the way home to Massachusetts. She remembers the bartender “coughing all over me,” and within a week, she and Gordon were both flat on their backs with a debilitating illness. They never learned if it was COVID-19 because no tests were available at the time.

Meanwhile, order cancellations started pouring in.

On March 14, the day after Bush called off Canoecopia, then-President Trump declared a national state of emergency. Wisconsin and many other states announced restrictions on gatherings. Many of the stores where Colby and other paddlesports manufacturers sell their products were ordered closed. Others shut their doors voluntarily or simply forecast a slow season and slashed orders accordingly. One major kayak manufacturer was stuck with $2.5 million worth of boats just sitting in a warehouse. In April, the entire outdoor industry was in freefall; a survey by the Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, a coalition of trade associations, found that nearly 80 percent of member companies had laid off or furloughed workers.

COVID-19 rocked the paddling industry back on its heels. The businesses most integral to the sport—shops and outfitters and small manufacturers—also tend to be the most vulnerable to short-term economic shock. Local retailers don’t just sell boats and paddles and life jackets. They guide new paddlers and attract seasoned ones, dispensing advice and sharing stoke. Without these gathering places, it’s not just the industry that would be in trouble. The culture of paddling was also at stake.

The same week Canoecopia was canceled, my kids’ school closed indefinitely. My first thought was to go paddling. A weeklong canoe trip has been on our spring break agenda for the last couple of years, but with four families and kids in three different school systems, we’d never been able to make the dates work. Suddenly, the conflicting schedules that had kept the trip bouncing around the calendar went away and for about 48 hours, the trip was on.

Then we began asking ourselves some uncomfortable questions. Is it safe, or responsible, to travel across three states? What if we bring the virus to a community that isn’t prepared for it? How, in God’s name, do you enforce social distancing on a pack of semi-feral kids?

Reluctantly, we canceled. I found myself in the novel position of having six weeks off, and not paddling once. This was fairly common in my circle, where friends stayed off the water either by choice or circumstance. My daughter’s outrigger canoe season was postponed and then canceled. National parks were closed, and river permits revoked. For the first time in 60 years, not a single boater ran the Grand Canyon in April.

In those early days, many of us thought the pandemic would last a matter of weeks, or perhaps a couple of months. When it became clear this coronavirus wasn’t so much an interruption in our schedule as a completely new paradigm, paddlers began to think of paddling not as breaking quarantine but a way to get through it.

The boom begins

Some saw the trend sooner than others. Kelly McDowell, the owner of The Complete Paddler in Toronto, recognized a surge in demand from the very start of the city’s two-month lockdown, which began in March.

“Paddling was going to be one of the only physically distancing activities you could do outside,” he said. “Because it’s so populated here, it was even hard to go for a walk in a park because everybody was walking in the park.”

The Complete Paddler is one of the bigger paddling stores in North America but, compared to big-box chains like REI, MEC and Dick’s Sporting Goods, it lacked the cash to ride out an extended sales drought. Still, while many big retailers slashed orders, McDowell doubled down on paddlers. He knew in his gut they wouldn’t stay off the water for long.

Contrast this with Canadian retail heavyweight MEC, McDowell said. “They just canceled their orders and shut the doors, which was the biggest mistake they could have made.” Meanwhile, McDowell took every boat his suppliers could deliver and sold them all—even though no customer was allowed to set foot in his store for two months.

“I would put the product on the front lawn, no matter what it was—a paddle or a boat or a life jacket—and sanitize it and then go back inside and lock the door and wave to them through the glass,” McDowell said. He did this 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Demand was insatiable.

In Madison, Bush ran a similar procedure at Rutabaga.

In the early days of the pandemic, still reeling from the financial repercussions of canceling Canoecopia, the paddling community kept Rutabaga afloat. Like McDowell, he was confident paddlers wouldn’t stay off the water for long; the challenge was keeping the lights on until they could come back. Bush urged clients to buy gift cards to redeem later and they responded by snapping up “mid-five figures” worth of gift cards, said Bush, who also took out a loan from the Small Business Administration to make payroll. Through the depths of the pandemic, he didn’t lay off a single employee.

When restrictions began to ease in late spring, his business went gangbusters. “Our rentals this year tripled, and we have people coming in to buy boats who have never paddled before, saying ‘My friend tried it and said it’s great and I should buy a boat,’” Bush said. “And they do. One guy backed up here with a Sprinter van and said, ‘I need five kayaks.’”

It was the same everywhere. The boom was like an inventory reset. Gear that had languished for months or years walked out the door in the arms of happy, if somewhat mismatched, new paddlers. None seemed to care if their new life jackets came in colors that had been discontinued (for good reason) three years before. They just wanted to get on the water.

By the time The Complete Paddler was allowed to reopen on May 19, the retailer didn’t have anything left to sell. “We’re a big store, 10,000 square feet,” McDowell said. “And we didn’t have one boat on the racks. We didn’t have one paddle. We didn’t have one PFD.”

Still, people lined up outside the door, ordering boats and gear sight-unseen.

The reason for the shortage was twofold. First, demand was through the roof, as people who had been cooped up for weeks looked for ways to get outdoors safely. Paddling is at the top of that list. While many faced layoffs and economic uncertainty, it’s also true every American adult received a stimulus check for $1,200—about the price of an entry-level paddling setup.

By June, retailers that had slashed orders in March were buying everything they could get their hands on, but there weren’t enough boats and gear on the continent to satisfy demand.

The paddlesports industry rallies together

Many companies had been forced to halt production during mandatory lockdowns, and the supply chain was in disarray. Essential parts and materials were delayed or unavailable. Before they could resume production, manufacturers had to figure out how to keep their workers safe, and early in the pandemic there was a critical shortage of personal protective equipment.

Several paddlesports manufacturers jumped in to fill the void. Lightning Kayak in Minneapolis shifted production from fishing kayaks to face shields. Eddyline made a similar pivot from sea kayaks, starting with a prototype cobbled together from kayak parts in its suburban Seattle factory. British Columbia-based Mustang Survival put its life jacket and drysuit expertise to use, making reusable hospital gowns, filling a desperate need at hospitals.

Even as the number of new paddlers spiked across North America, the ways for them to integrate with and revitalize the paddling community were fewer.

YakAttack, which makes injection-molded kayak fishing accessories in Farmville, Virginia, designed PPE products, including a replacement shield for positive pressure respirators, a face shield, and an emergency respirator that can accept whatever filter media is available. The company brought them to production within days and provided them at cost to local hospitals and first responders.

“Knowing we had the capability and knowing there was an urgent need out there, we decided it would be a shame to just sit out the shutdown,” said YakAttack owner Luther Cifers.

Helping others in a crisis is second-nature for paddlers. As the saying goes, we’re all between swims, and most of us have been on both ends of the throw rope. Shifting to PPE production was a way for companies to give back to their communities, but it also proved to be a good self-rescue technique. It allowed companies to keep key staff working through the height of the crisis, so production could go full steam when kayak orders bounced back.

And did they ever bounce back.

The boom in full swing

“Instead of the 10 boats they usually ordered, they wanted 20,” said Michael Squarek, sales and marketing manager at Delta Kayak. “We shipped the 20, and they were already sold before they hit the sales floor, which is absolutely unheard of. It’s nuts.”

In late October, Delta was still building and shipping kayaks to sell this season. Virtually every North American manufacturer is doing the same. “I’ve got boats I ordered in July that aren’t here yet, and I’m still taking them because we’re selling boats still,” Bush said at the end of October—this in Wisconsin, a state that would soon be covered in snow and ice. “People say, ‘I’m going to need this for next year,’” Bush said.

In my town of Dana Point, California, the launch spot we call Baby Beach was wall-to-wall seven days a week. Onshore it was nearly impossible to maintain a six-foot perimeter, prompting my wife to issue an executive order to the family: No more paddling during peak hours. Eight to 10 a.m. became our sweet spot—after the one-man outrigger and serious SUP racers finished their morning workouts, and before the daily onslaught of paddlers in every craft imaginable, from Walmart inflatables to rec kayaks and every type of standup board. Judging only by the proportion of backward and upside-down paddles, many in this crowd are brand new to paddling and figuring it out on their own.

While sales and participation soared after reopening, paddling instruction was hard to come by. The Complete Paddler, which normally runs paddling courses throughout the season, didn’t hold a single class all summer long. McDowell said the risks were simply too high, and on top of that, he didn’t have the boats. He sells off his rentals each fall and replaces them in the spring, but this season every boat he could get his hands on went straight home with a customer.

Jason Self, who runs coastal kayak tours in Trinidad, California, had plenty of boats but was forced to sit out the spring grey whale migration, a two-month bonanza accounting for about 40 percent of his yearly business. “We missed all of that, which was really scary,” Self said. “But one thing that really worked in our favor was a giveaway where if people bought a gift certificate for a future tour, I would match them by donating one to local frontline workers.”

When he realized the out-of-town visitors, who provide the bulk of his clientele, wouldn’t be coming due to travel restrictions, Self shifted his entire marketing budget to local radio. He watched in disbelief as his rental business grew more than 500 percent over 2019 levels. Self says it remains to be seen whether those frontline workers and rental clients will translate into a more vibrant local paddling scene in Trinidad.

That’s a big question mark everywhere, particularly with so many traditional paths into the sport closed due to the virus. Summer camps, a source of canoe tripping skills and inspiration for young people, were shut down last summer. It’s not clear whether they’ll be able to operate normally this season.

Many paddling clubs canceled group outings or shifted to informal channels like online meetup groups. Major gatherings such as Gauley Fest were canceled, and the Green Race, typically a raucous affair with hundreds of spectators crowding the Narrows, was livestreamed. Even as the number of new paddlers spiked across North America, the ways for them to integrate with and revitalize the paddling community were fewer. Despite these hurdles, the enthusiasm is unmistakable, and it bodes well for the sport.

Why paddling?

The virus has infected more than 30 million people in the United States and Canada and is responsible for more than 550,000 deaths. COVID-19 has broken families, caused economic distress, and brought heartache and loneliness to millions. It feels strange to spin this tale of renewal from something so destructive, but as paddlers, we know and celebrate the healing power of water.

“Being on the water is soothing,” Lili Colby told me when I asked why so many people seemed to flock to the sport during the pandemic. “It’s an escape. It’s a place to have a mental reset, and hopefully, more people have discovered what we paddlers have known for a long time.”

For those of us who have found so much joy in paddling, it’s comforting to know that others will find healing on the water. The question remains whether paddling will be a temporary salve or a lasting one.

When I put this question to paddling friends and industry insiders, most agree the boom will last. While industry folks are understandably guarded with their sales figures, the adjectives flying out of their mouths—wild, crazy, off-the-charts, unprecedented—leave no doubt 2020 was an extraordinary year. As Rapid Media Publisher Scott MacGregor told me, “We just had one of the best seasons ever in paddlesports—and the switch was only on in June.”

MacGregor, for one, thinks 2021 will be even bigger. Why? “Nobody I’ve talked to in paddlesports or in the medical field believes this summer won’t also have a version of mandated social distancing,” he said. That means a replay of this last season, with one crucial difference. Instead of deciding to try paddling on a whim, these new boaters have had an entire winter to think about what to do and what to buy—where to go, courses to take, and the gear they’ll need. Come summer, travel restrictions are likely to be fewer, instruction more available, and paddling shops stocked and ready.

“This year,” MacGregor says, “is going to be the best year we’ve ever had in paddlesports.”

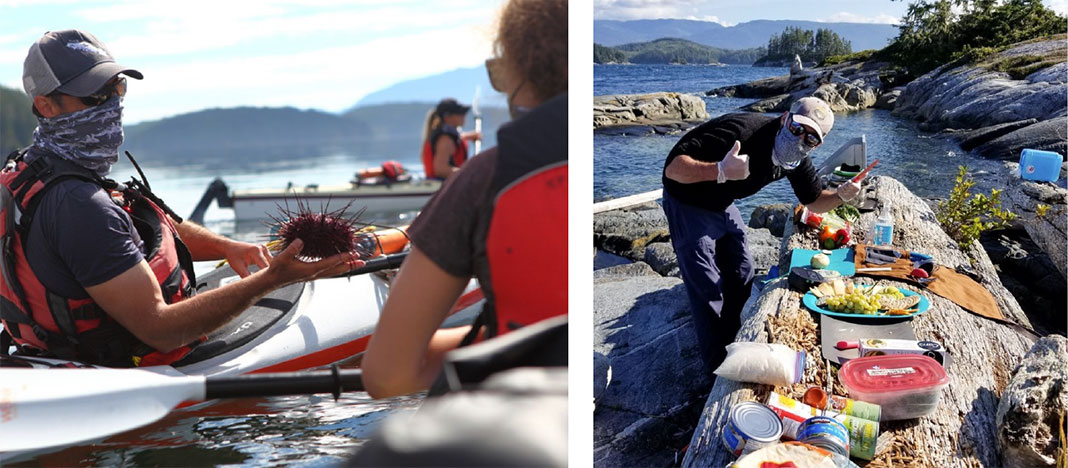

The original social distancing activity. | Photo: Brendan Kowtecky

Jeff Moag is the former editor of Canoe & Kayak and the contributing editor of Paddling Magazine’s trade publication, Paddling Business.

Great article Jeff! The implications from COVID-19 were wide and varied depending on the market. For example, the powerboat market also saw a dramatic dip and then huge growth in 2020 as millions flocked to the water to social distance under power. Recent research from Info-Link.com shows that 415,000 first-time boat owners hit the nation’s waterways last year. Of course, many of them had no training and as a result, many states are reporting boating casualties are up by at least 20%. The recreational vehicle and bicycle industries also saw explosive growth while tourism industries such as hotels, airlines, rental cars, and cruise ships were shuttered. Who would have guessed?