- Bloodsucking leeches use microscopic teeth to break the skin of their host and secrete an anti-clotting enzyme into the wound to keep the blood flowing.

- Healers have used leeches for thousands of years for their ability to keep blood from clotting. The anti-coagulant in leech saliva prevents blood clots better than most pharmaceuticals. Today, leeches are used during some surgical reattachments of amputated limbs.

- The word leech is thought to be a derivative of laece, the Old English term for physician.

- Leeches are distinct among invertebrates in that some species of leech will nurture their offspring.

- When a leech clamps onto a host, it will stay attached until it fills up. A leech can ingest enough blood to expand its body size by a factor of 11.

- Salting and burning a bloodsucker are effective means of removal, but they may cause the leech to barf up its meal. A leech’s stomach bacteria can infect the wound. Menthol-based heat rubs are the safest way to remove a leech.

- A separate order of worm-like leeches, common in freshwater, don’t have teeth or a love for blood.

- In 1851, Dr. George Merryweather introduced the Tempest Prognosticator, a barometer using leeches housed in small bottles. He claimed that when a storm approached, the leeches became agitated and tried to climb out of the bottles, triggering a small hammer to strike a bell. The British Navy bought none.

- Robin Leach was the host of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, a show profiling the lives of rich bankers, lawyers and politicians, a whole different kind of bloodsucker.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

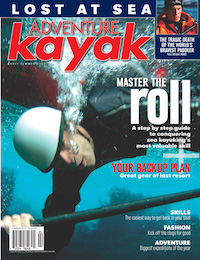

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions