Just a couple hundred miles from Rub’ al-Khali, the largest sand desert on Earth, one of the world’s longest and most unusual manmade rivers flows under the scorching desert sun.

The Wadi Adventure whitewater park was conceived as part of a tourism vision for Al Ain, the fourth largest city in the United Arab Emirates, just 90 miles from the glitzy metropolis of Dubai on the Persian Gulf coast.

In 2012, when Wadi opened its doors to the public, 50,000 visitors enjoyed the plush white pillows and shaded lounge chairs of the VIP zone next to the artificial rivers. But mixed in with the tourists was a core group of canoeists and kayakers with a mind to train in the off-season while avoiding an expensive flight to Australia, the usual winter training ground for European paddlers.

Welcoming the international crowd of slalom athletes is Fergus Coffey, the whitewater manager at Wadi Adventure. A lifelong paddler, Coffey guided rivers in North and South America and ran the kayak program at the U.S. National Whitewater Center (USNWC) in Charlotte, North Carolina, before getting offered the gig at Wadi.

“I had the opportunity to come to the UAE and set up a completely new facility,” he says. “It was too odd to pass up.”

Inspired in part by the USNWC, Wadi was originally built as a slalom site, but given the UAE’s tourist traffic, a surf pool was added to increase wider demographic appeal.

Now, as word in the paddling community spreads, Wadi Adventure is becoming a winter wonderland for whitewater paddlers from all over the world, each with a different take on its unlikely desert waterways.

THE UNEXPECTED OASIS

It was 6 a.m. on January 25 when French paddler Nouria Newman and her Caimen Storm kayak arrived at Dubai’s international airport. Along with her coach and four teammates she had driven to the airport in Lyon, France, and taken a six-and-a-half hour flight that landed her in a different world.

The Fédération Française de Canoë-Kayak had coaxed her into signing onto a two-week training intensive in the middle of the desert at Wadi Adventure, Al Ain’s newest city planning success and the Middle East’s first whitewater facility. It was much warmer than the zero degree winter training conditions in Toulouse and cheaper than flying to Australia.

Last year she had managed to talk her way out of the training venture but this year she didn’t get off the hook so easily.

Exhausted from the flight, she nodded off as they drove the E66 towards Al Ain, a route cutting straight south through an otherwise blank desert landscape. When she awoke it was still dark but perfectly spaced streetlamps lit the way, and in the distance the rising sun started to shine on Jebel Hafeet, one of the UAE’s highest mountain peaks.

“When you actually enter the place it feels like Disneyland,”

says Newman, recalling her first impression of Wadi Adventure as the drive from Dubai finally ended.

Paddlers from Italy, Germany, Russia, England, America, Switzerland, Slovenia, Japan, Slovakia and Czech Republic joined Newman and her team. From June to September, Newman’s used to seeing competitors at races around the world, but to be all in one place during the off-season was something new.

“It’s like a summer camp, coming here,” she says. “We have barbecues and hang out and turn into slalom geeks for two weeks.”

Paddlers all stay in fully furnished chalets just off site and share meals when they can. They go on day trips

to Abu Dhabi. They take camel rides. On off days, some paddlers visit the massive indoor theme park of Ferrari World or the indoor ski slopes in Dubai. Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Maseratis with tinted windows roll past the park.

“Even a Russian oligarch will be able to find something expensive here,” says Coffey.

But at the park itself, cell phones turn off and crystal clear waves flowing from a mysterious water source become Newman’s primary fixation.

THE PLAY PARK MIRAGE

While Nouria Newman was making rounds of the Wadi’s three whitewater runs, Ciarán Heurteau, a seasoned slalom kayaker, was taking a break from the scene.

Heurteau made the trip to Dubai with two teammates and a coach as part of the first group of kayakers to pass between the slalom gates after Wadi’s grand opening in 2012. He left feeling unsettled and uneager to return.

It’s no secret that the UAE was built on an oil regime and hosts some of the wealthiest business tycoons in the Middle East. Al Ain itself was home to the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al Nahyan, the first president of the UAE. The nearby Rub’ al-Khali, a desert roughly the size of France, is home to the world’s largest oilfield, the Al-Ghawār.

When Heurteau’s not paddling, he lives in a small village in Northern Ireland where he avoids using plastic bags and is conscious of the compost that comes from his morning breakfast. For him, this artificial river was too far from the green lifestyle he leads. “The amount of money that’s just wasted, it blows you away,” he says. “It’s easy to go there to train and just not look at the whole other side of it.”

The crystal blue waters of Wadi’s 1,100 meters of faux river are sourced from municipal lines that pump and desalinate water from the coast in Abu Dhabi, about 100 miles west of Al Ain.

Ninety-four million gallons of water recirculate through the concrete channels with up to a quarter of an

inch of depth lost to evaporation each day. Five vertical pumps run for about 12 hours at a time to keep the water flowing, says Coffey, and two conveyer belts transport paddlers from the bottom of each course to the pond at the top.

For Heurteau, the illusion of a pristine desert oasis was more unsettling than magical, more manufactured fantasy than reality.

“I reckon more and more this is where people will head for training. There are no more races on natural rivers any more so it makes sense to train in places like this.”

The line goes quiet for a few seconds.

“It’s a very different feeling paddling on artificial courses,” he says. “You can see the shift in people’s thinking.”

Al Ain is known as the Garden City of the United Arab Emirates. | Photo: MICHAEL NEUMANN

THE BLISSFUL DESERT VOID

Under the black desert sky with the course floodlights turned off and only the sound of running water ringing in his ears, Vávra Hradilek finally found the desert space he’d been seeking.

In the pitch black of the night with only a photographer following him from land on an otherwise empty river, the Czech paddler got in his kayak and began running the course.

“I could only hear the water without any vision, so from memory I just went through the strokes,” he says. “It was amazing.”

For Hradilek it was a moment of pure kayak bliss.

During the day, intervals of 25 paddlers at a time would take turns running the slalom course, watching in front and behind them to avoid a collision. Along with other European paddlers, he and his 34 Czech teammates stayed in a massive block of chalets beside the river and fired up the barbecues to cook their meals together.

Hradilek was even more crowded than most with a film crew following him around for a week tracking his training and off time for a short film.

“I think summer camp is the right word. It’s all the paddlers in Europe in one place hanging out,” he says. “I’ve been in the circuit for a long time so I know most of the paddlers who come out on race days but here there were so many new people.”

The course offered night sessions to anyone interested in taking on the whitewater away from the beaming sun.

For the slalom vet these spacious hours were the highlight of his month- long intensive, his escape from the claustrophobia of a packed whitewater course. Surrounded by the vast sprawling sands of the Rub’ al-Khali—a desert dubbed the Empty Quarter—all it took was for the lights to go out for him to experience bliss in the desert void.

Katrina Pyne is a freelance journalist whose mind is constantly drifting from her desk job to quiet untouched rivers and chaotic whitewater parks. At heart, she’s still a wilderness guide.

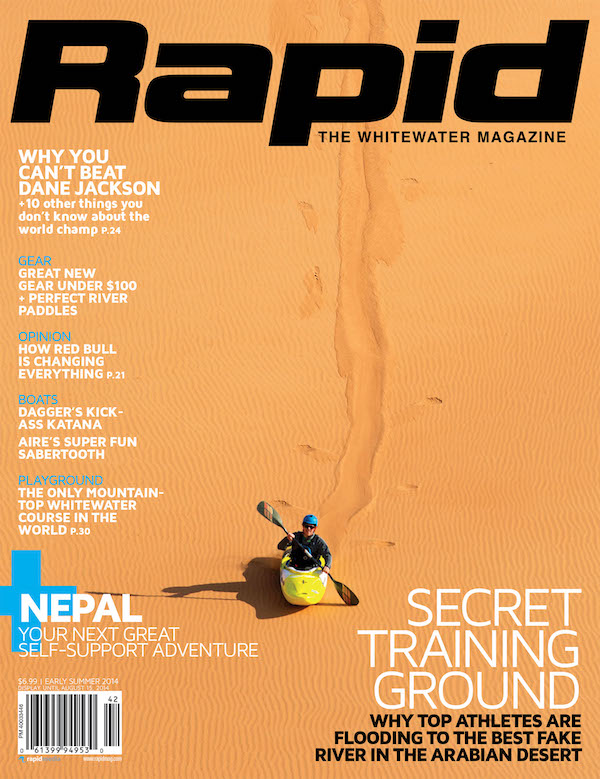

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2014 issue of Rapid Magazine. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2014 issue of Rapid Magazine. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions, or browse the archives.

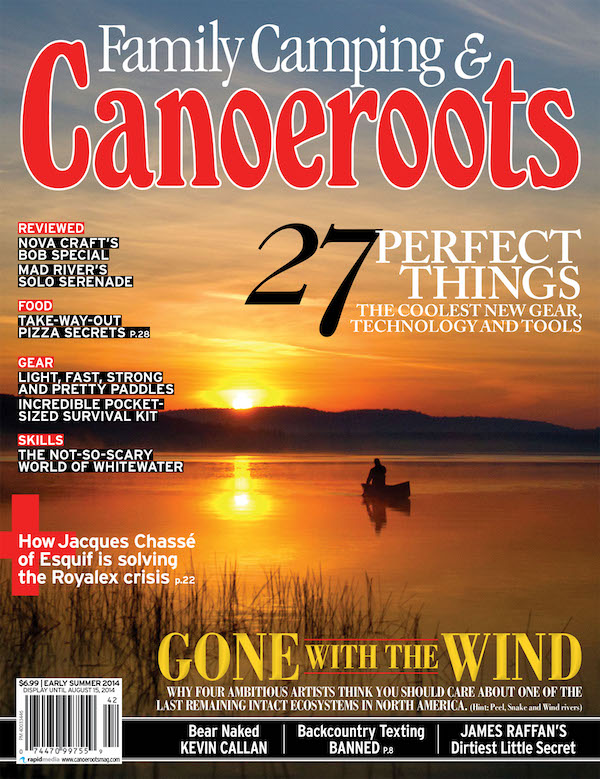

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots and Family Camping, Early Summer 2014, on our free

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots and Family Camping, Early Summer 2014, on our free

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots Early Summer 2014.

Get the full article in the digital edition of Canoeroots Early Summer 2014.

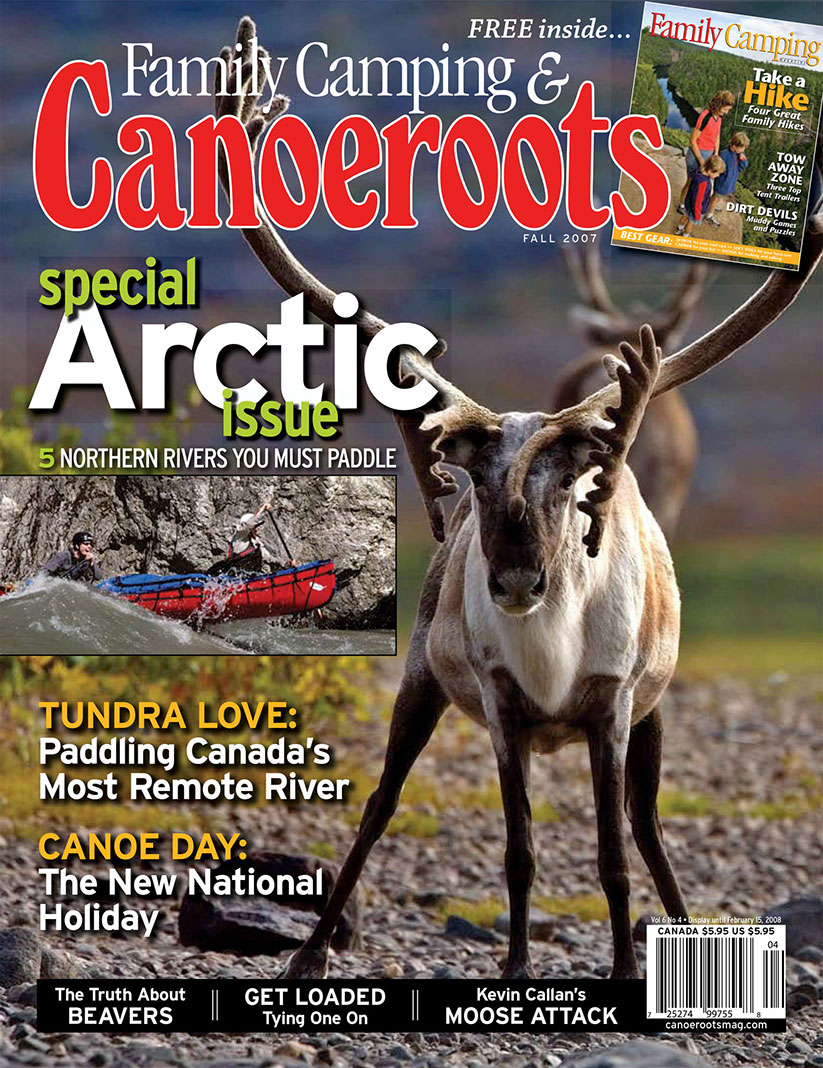

This article was first published in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Fall 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.