“When a nor’east or a nor’west comes in hard, the arse can really fall out of it,” Christopher Lockyer tells me as the road squeezes to a single lane and doglegs between roof rack-high stacks of lobster pots.

In places, the neck of Cape Forchu is so narrow it’s little more than a causeway. A rugged headland that juts south from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, the cape’s crescents of surf-pounded sand and rows of weathered fishing wharves are lapped on one side by the Bay of Fundy and on the other by the unforgiving North Atlantic. It’s easy to imagine a northerly blow ripping across here with arse-spanking fury. In a couple of months, the docks will be bustling with lobstermen, but on this bright late-September morning our convoy of kayak-topped vehicles is the only sign of activity.

Colorful local expressions slip easily from Lockyer’s mouth. Beguiling host of the inaugural Bay of Fundy Sea Kayak Symposium, the bay is in his blood. Lockyer has spent most of his adult life on the bay, first as a lobster fisherman and later as a sea kayaker. His family, in- laws and friends have all worked on the bay in boats of various sizes. Now a GIS tech in Halifax, he also runs Committed 2 the Core Sea Kayak Coaching and is raising his own family near the small town of Truro, Nova Scotia, at the bay’s head.

Home to the world’s largest tides and a wildly varied coastline—from the rust-colored cliffs and sea stacks of Cape Chignecto to rugged archipelagos of glacially-formed islands wreathed in fickle currents—the Bay of Fundy is a natural paddler’s playground. It’s remarkable, then, that its potential as a world- class kayaking destination has remained largely untapped.

When Lockyer caught the kayaking bug in 1994, he traveled to paddling events in Wales, Scotland and Georgia to develop the advanced skills that would allow him to play in Fundy’s dynamic tide races and rock gardens. Five years ago, he realized Maritimers needed their own venue for sharing ideas and connecting with other paddlers. Working with Paddle Canada, Lockyer helped develop the Atlantic Paddling Symposium, a multi-discipline event hosted in a different Atlantic province every year. Then, in 2012, the bay called him back.

“All of the Atlantic Symposiums were 75 percent sea kayakers,” he says, “so I figured, why mess around chasing canoeists? Why not do an event just for kayakers?”

There was never any doubt where the new event would take place.

Salted Chocolate

Amidst bucolic farmland and sleepy hamlets, tucked deep inside the Bay of Fundy, the Shubenacadie River plays a twice-daily game of Jekyll and Hyde. When the Bay’s 56-foot tidal exchange is on the ebb, the Shubenacadie—or Shubie, as it’s known locally—flows sedately to the sea. But on a flood tide, the lower reaches of the Shubie transform into rollicking rapids flowing upriver, the bay’s briny seawater charging between high banks of slick red mud. Nothing escapes a liberal plastering of that famous Shubie muck; even the river runs a rich, chocolatey brown.

A full harvest moon has brought the highest tides—and largest rapids—of the month, and Lockyer has brought 10 of the global paddling community’s top coaches to experience his backyard river before the very first Bay of Fundy Sea Kayak Symposium (BOFSKS) kicks off. A dozen eager students have also signed up for the pre-event fun.

We meet in the historic village of Maitland—formerly a shipbuilding center and still home to a wealth of fine Victorian architecture—at sunrise, up early to put on the river before the incoming tide.

potential comes naturally to Paul Kuthe. | Photo: Virginia Marshall

I tag along with guest coaches Matt Nelson, visiting from Washington’s San Juan Islands, and Rowan Gloag, hailing from British Columbia’s Vancouver Island.

We’re joined by Fernando, a local Nova Scotia paddler, and Haris, a sea kayak instructor from Chicago. Matt is tasked with seeing us down (up?) the river safely, as well as hunting out the best play spots along the way.

In the quiet stillness of the morning’s slack tide we wait expectantly, straining to spot the vague ripple on the horizon that signals a coming tidal bore. After an hour of anticipation and holding position against a weakening ebb, the current turns almost imperceptibly, then begins to pick up speed.

The bore—a river-wide, surfable wave that pushes upriver, promising 10- or even 20-minute-long rides—never materializes. Formation of the Shubie tidal bore requires a specific alchemy of factors, including tidal exchange, river volume, wind speed and direction, and the

depth and width of the channel at the river’s mouth on Cobequid Bay—it’s by no means a sure thing. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to play.

Wave sets soon develop over under- water sandbars and at constrictions, the features building and flooding out with the rising tide. Imagine watching the daily transformation of a snowmelt or glacier-fed river on super fast-forward. Rides are as fleeting as the features themselves, and we chase Matt around the wide, lumpy channel of the Shubie like hounds on a scent. He seems to have an uncanny sense of where the next wave set will materialize, rising from the coffee-colored water like a surfacing sea serpent.

“I’m so excited to be here!” Dawn Stewart gushes when I catch her bump- ing merrily through head-high haystacks. Backwards. On purpose. Stewart traveled all the way from North Carolina, she tells me, for Fundy’s challenging conditions and the event’s world-class coaches. “I’m star-struck, it’s like…” she pauses, searching for the right word, “Hollywood!”

The day’s best rides are had in the “Killer K” upstream of a bluff known as Anthony’s Nose. Actually, relative to

the sea, this kilometer-long wave train is downriver from the Nose, but directions on the Shubie change with context. “Yeah, it’s a bit confusing,” Matt admits, “just think of the river in relation to the prevailing current.”

Haris scores a dream surf—nearly a minute of carving gracefully on the glassy leading wave. I fall down a four- foot face, sliding sideways into a muddy trough as the Shubie crashes playfully across my shoulders. For a moment, I view the world through a barrel of this strange, salty river and feel as though I’m surfing through one of those TV commercial swirls of molten chocolate.

fruitless to argue with fate | Photo: Virginia Marshall

Home of the Whopper

“Look at the coaches Chris brought in for this event—these are the big dogs, the coaches known for paddling rough water really well,” muses Justine Curgenven. We’re sitting cross-legged on our beds and I’m doing my best to conceal my giddiness—OMG! I’m bunking with a big dog, the fearless, famous star of This is the Sea.

Mercifully oblivious of my hero-worship, Curgenven continues, “If you want to showcase Fundy as an exciting, chal- lenging kayaking destination, these are the paddlers you invite.”

The day before, Lockyer had surprised Curgenven and the other coaches with another local play spot. After our Shubie run, we hustled into vehicles—mud- slicked drysuits still tied around our waists—and followed him through storybook-pretty countryside. Rolling pasture, tidy collections of impeccably restored or charmingly derelict clapboard homes, and the bay’s ruddy waters flashed past the windows. A sign announced our arrival in Walton, “home of the Walton Whopper.” But Lockyer hadn’t brought us here for burgers.

Beneath Walton’s solitary bridge, the tide was ebbing. Before long, what began as an innocuous green tongue had transformed into a chundering, kayak-eating maw—the real Whopper.

The mayhem that followed was not only a glorious spectacle of kayak carnage, but also a lens to focus the diversity of talent gathered in this unlikely spot: West Coast hotshot Paul Kuthe’s controlled carves and foam pile flatspins, informed by years of paddling whitewater rivers. Welsh coach Nick Cunliffe’s inimitably fluid style, as smooth as the wave itself. California surf kayak champion Sean Morley’s hard-charging power, Great Lakes coach Ryan Rushton’s tenacity, Curgenven’s whack-a-mole-like resilience.

Kuthe seemed a lock for the inaugural Whopper win with a series of cartwheels that had onlookers cringing at the audible thuds of his bow and stern striking submerged rocks. Then New Zealand paddler Jaime Sharp entered the fray for a final wild bronco ride. His rightful claim to the title was settled when his borrowed Valley Gemini endered and pirouetted on its bow to the wild cheers of battered coaches and baffled spectators alike.

If the Whopper confirmed Curgenven’s assessment about Lockyer’s choice of BOFSKS ambassadors, it also demon- strated in no uncertain way Fundy’s ability to humble even the most experienced paddlers.

When Life Gives You Bananas

“The ‘check engine’ light has been on the whole bloody drive,” Rob Avery gripes as we pull out of Maitland and turn his well-abused, early ‘90s vintage Chevy Suburban toward Argyle, 350 kilometers distant.

Actually, Avery—an affable Brit now residing in Seattle—isn’t the truck’s owner; it came attached to a trailer full of kayaks he picked up in Rhode Island several days earlier. “I slapped a banana sticker over the light so it doesn’t bother us any,” Avery continues, chuckling with satisfaction. From where I’m seated shotgun, I can just make out the ominous orange glow through a blue-and-gold Chiquita logo.

An hour later, a sudden clunking noise erupts from beneath the truck’s faded green hood and we drift falteringly into the shoulder. Behind us, the convoy grinds to a halt. At least the symposium can’t start without us—half of the coaches are standing with me on the side of Highway 102 somewhere outside Halifax.

One tow, two hours and a spirited round of touch wrestling and tailgate lunches in a Petro-Canada parking lot later, we get the bad news: the Suburban isn’t going anywhere without a new engine. Abandoning the truck and its attendant $4,500 repair estimate at the garage—and cramming the remaining vehicles well beyond recommended capacity with people, boats and soggy paddling gear—we continue the four-hour drive to Argyle.

Ripple Effect

Ye Olde Argyler Lodge occupies an enviable perch steps from Lobster Bay; its spacious dining hall, wide wraparound verandahs and grassy lawns overlook sunset views of the bay’s sleeping islands. Fresh sea air wafts across a clean cobble beach. Lockyer knew the moment he saw the lodge that he had found the Bay of Fundy Sea Kayak Symposium’s home base.

Flung on the very tip of Southwest Nova Scotia, Argyle, Yarmouth and the neighboring villages of the Acadian Shore occupy a scenic but socioeconomically depressed hinterland between the Bay of Fundy proper, and the province’s more prosperous South Shore. Although the lo- cal lobster and scallop fisheries survived the early 1990s Atlantic groundfishery collapse, like the rise and fall of the tides that inform all aspects of Maritime life, an ebb was coming. When the ferry from Bar Harbor, Maine, to Yarmouth ceased operation in 2009, it gutted the region’s all-important summer tourist economy. With the BOFSKS, Lockyer, the organizing committee and their municipal tourism partners hope to help turn the tide.

“There’s phenomenal paddling here, it’s just taken 15 years for the rest of the world to discover it,” Sue Hutchins, a local photographer, avid expedition paddler and Maine transplant, tells me over a plate of the lodge’s fresh Fundy haddock and scallops au gratin. I learn about the fog-shrouded drumlins of the Tusket Islands, of Brier Island’s sheer cliffs and nutrient-rich waters teaming with whales and seabirds. Witness firsthand the hospitality of the proud Acadian French people who have lived and worked on these shores since 1653.

Indeed, it is the warmth and generosity of the locals—more so even than the skills of the coaches or the sublimity of the paddling environs—that sets BOF- SKS apart. After three days—heck, three hours—I feel like a member of the family.

The initial impact of our modest kayaking clan gathering here for a long weekend may not be enormous, but the lasting effects are immeasurable. “You are 130 stones sending your ripples far into the pond,” Lockyer tells the paddlers gathered on the Argyler’s lawn, “spread the word, tell your friends.”

Fame and Forchu

Cape Forchu’s fishing sheds lean with silvered siding and vacant windows into the wind, awaiting Dumping Day, the late-November start of lobster season. Brightly painted trawlers rest at drunken angles on drying sandbars. Swell rolling out of the Atlantic booms against the cape’s polished cliffs, sending spray far above our heads.

I’ve joined Matt Nelson and Jaime Sharp, along with a handful of daring

students, for a rock-hopping session around the cape. This tour, like all of the symposium’s most demanding sessions, is rated comfortable intermediate, rather than advanced, because as Lockyer will later explain, “We wanted to stay away from that scratch-your-balls, bang-your-chest connotation.”

Matt is showing participants Jerome Trottier and Ted Tibbetts how to ride the “swell-evator”—dancing nimbly up and down the cliff face with the surging rise and sucking fall of the ocean swell. The classic symposium stigmas—overstated conditions, underwhelming classes, inflated egos—fall away like seawater down the rocks. There is such a wealth of expertise, abundance of beautiful coast and variety of challenge here; it’s all but impossible to be disappointed.

While the rough water classes enjoy ideal sea conditions, the weekend’s surf sessions find little action on area beaches. Johanne Lavoie, an adventurous Montreal paddler who counts her city’s high-volume Lachine Rapids as a favorite after-work sea kayaking spot, found her Surfing in Style class relocated to the sheltered waters of Lobster Bay, alongside the event’s milder sessions.

“Nick [Cunliffe] started the class with edging our boats on flatwater and I thought ‘F***, not this again! Is this all we’re going to do?’” she tells me later that afternoon, “But then he added a small correction, and then another and another—he kept me busy.” When Cunliffe moved their practice to an area of swift tidal currents and swirling eddies, says Lavoie, “It was the perfect progression.”

Lockyer is enormously pleased with the first annual BOFSKS. As the weekend winds down, he’s already sharing the event’s 2014 dates with participants and coaches, and wondering what effects their small ripples will have on his beloved bay. The tide, it seems, is turning.

The Bay of Fundy is many things—world-class and down-home, brutal and beautiful, intimate and enigmatic, pantry and playground—but it’s no longer a secret.

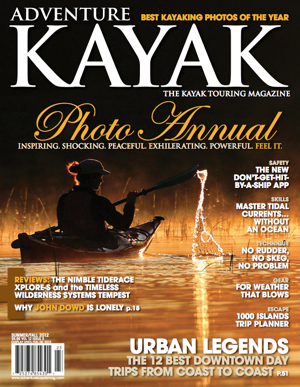

This article first appeared in the Spring 2014 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2014 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article first appeared in the Adventure Kayak, Spring 2014 issue.

This article first appeared in the Adventure Kayak, Spring 2014 issue.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2013 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2013 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Fall 2012. Download our free

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Fall 2012. Download our free

LifeStraw Water Bottle

LifeStraw Water Bottle Sierra Designs Backcountry Bed

Sierra Designs Backcountry Bed  Muddy Munchkins Boots

Muddy Munchkins Boots Sea to Summit Aeros Pillow

Sea to Summit Aeros Pillow Zem Gear U EX

Zem Gear U EX

So did Seaward get the dragons’ dough? The episode was filmed in Toronto in April of last year, but Seaward’s director of communications, Nick Horscroft, and the rest of the Seaward team have kept a tight lid on what went down in the Den. “At this time we cannot reveal any details about the show itself but it was a fantastic experience for the owners of Seaward Kayaks,” Horscroft said in a statement after filming.

So did Seaward get the dragons’ dough? The episode was filmed in Toronto in April of last year, but Seaward’s director of communications, Nick Horscroft, and the rest of the Seaward team have kept a tight lid on what went down in the Den. “At this time we cannot reveal any details about the show itself but it was a fantastic experience for the owners of Seaward Kayaks,” Horscroft said in a statement after filming.

This Field Test gear review originally appeared in the November 2013 edition of Paddling Magazine. Download our free

This Field Test gear review originally appeared in the November 2013 edition of Paddling Magazine. Download our free