This profile originally appeared in Rapid magazine.

Ben Marr was just nine years old when his dad bought him his first boat—a Perception Dancer. Four years later, he was rolling, cartwheeling and splitwheeling a Perception Jib and sitting down with Rapid publisher Scott MacGregor for a Q&A about the Jib in our Summer 2000 issue (“Small People, Small Boats,” page 32).

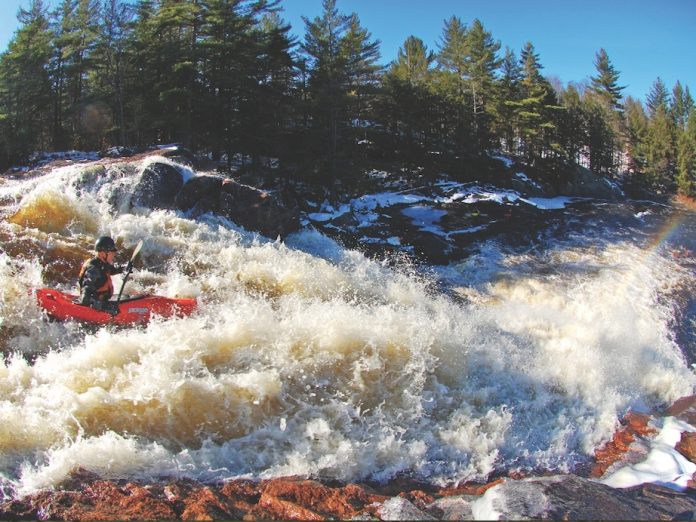

“I’ve had a long, gradual learning curve,” says Marr, now 24, about his road to becoming one of the world’s top big wave riders. “The Madawaska River trained me and my old man for the Ottawa River’s Middle Channel, and the Middle Channel trained us for the Main. I went from weekend warrior to summer resident.”

An invitation to the 2011 Whitewater Grand Prix gave him the chance to compete against an international who’s who of sponsored paddlers. Marr finished first in all three of the event’s freestyle stages and second overall.

It seems surprising, then, that Marr didn’t attend the recent Freestyle World Championships in Plattling, Germany. “I didn’t try out for the team,” he says. “Wave surfing and competition hole riding are completely different. You wouldn’t see me do well there.”

Behind his modesty is a preference for pushing limits on bigger features rather than smaller, more technical championship venues.

“Everyone was turned on by the Grand Prix,” he says, recognizing the impact that the much-hyped competition promised the whitewater community and his own career. “The format served my style way more than traditional freestyle competition.”

Still, Marr focuses more on having a good time than anything else. Case in point, his signature mullet. “It turns out the boys in the ‘80s were onto something,” he kids. “It’s a hit at parties and a great way to keep hair out of your face.”

He also still spends time on the river with family. This past March, he ran the Ottawa in a tandem kayak with his 83-year-old grandmother.

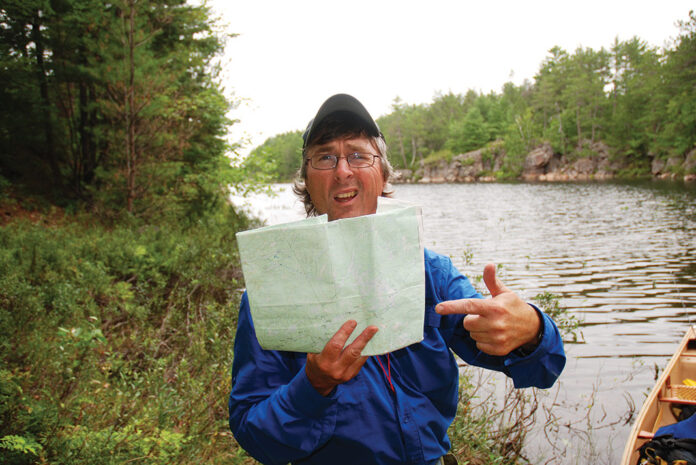

“My Dad took Gran down the Ottawa in a canoe once. After a flip resulting in a swim, my dad was no longer allowed to put her in such peril—my aunt’s rules. But Gran was keen for another go so I told her I would be happy to bring her down and we wouldn’t have to tell. She was stoked.”

With his performance at the Grand Prix and an international paddling resume that includes surfing many of the world’s most intimidating big waves, Marr seems a shoe- in for big time sponsorship. But pro circuit recognition has so far been elusive. “I would love to get my hands on some sponsorship dollars,” he says. “I would go on way more paddling trips and spend time focusing on racing.”

This article originally appeared in Rapid, Summer/Fall 2011. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Canoeroots Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Canoeroots Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.