It would be incorrect to say, “I’d like to launch my canoe, but there are so many inukshuks lining the shore I fear for the safety of my shins.” As plausible as this sentence is, the correct plural of inukshuk is inuksuit.

Pluralizing inukshuk was once something you rarely had to do, but enough would-be adventurers now so enjoy piling rocks into human-like figures that the lonely inukshuk has become a plurality.

Killarney Provincial Park in ontario has reacted by declaring them granite non grata. The backlash really got going when an inukshuk was adopted by the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games. Anti-corporate wilderness travellers declared inuksuit to be unfashionable eyesores.

What’s the problem, you ask? The inuksuit were confusing hikers in Killarney, where trails are marked with stone cairns. other objections are ecological in nature (the rocks are habitat for critters that are entitled to a cold, wet place to live) and cultural (southern inuksuit represent a co-opting of Inuit culture).

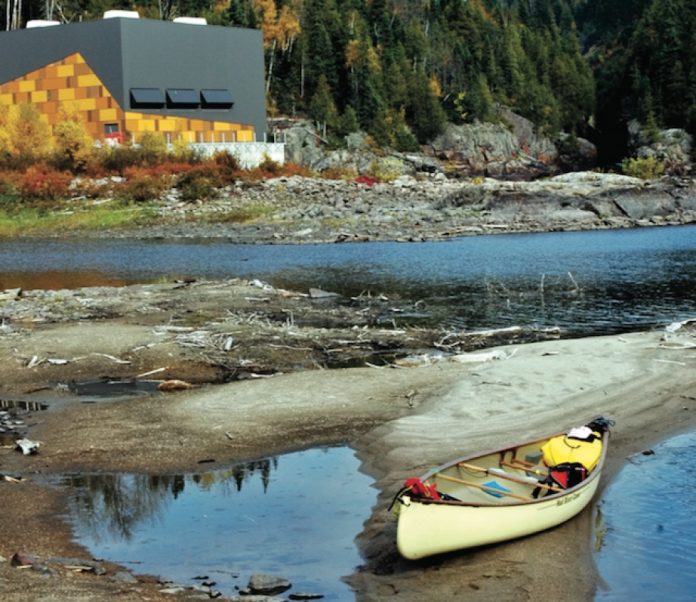

To these I add the tragic tale of how they slowed my progress down Quebec’s Noire River.

On day two we began noticing somewhat organized piles of rubble peeking out from rocky points. My trip mate—let’s call him Destructor—decided they had no place on the river and vowed to eradicate them.

The inuksuit ballooned in number as we paddled and Destructor began criss-crossing the river on an increasing frequency. our pace slowed as he tried to squeeze blood from stones.

As Destructor showed, the real menace is that inuksuit might divide the paddling community into two groups: one that likes to create while they recreate and another that won’t abide signs of a human presence near portage landings. But recent events show paddlers can’t afford to be fragment- ed like feuding religious sects.

To see why, consider John and Jim Baird. John Baird is Canada’s minister responsible for transportation. He’s the man who has dismantled the Navigable Waters Protection Act (NWPA), a 126-year-old law that protected both waterways and each Canadian’s right to paddle them. It was a law that said rivers were important for six generations of Canadians, and now it doesn’t.

Last summer Jim Baird and his brother Ted paddled the Kuujjua River on Victoria Island in Canada’s high Arctic. There they saw real inuksuit and stone cairns, some 300 years old, that had been built not because of an excess of ego or spare time, but because they served important functions in a severe land.

At Minto Inlet they stopped at a squat, man-sized cairn that housed a message from a party that had passed that way 157 years ago while searching for the Franklin Expedition.

The Bairds left the cairn standing of course. Victoria Island isn’t the sort of place that tolerates those who act rashly on the land or dismiss the past.

The law John Baird knocked down was only 31 years younger than that stone cairn. By pointing to a temporary downturn in the business cycle as the reason the NWPA had to go, Baird demonstrated all the wisdom of a pile of rocks, but none of the steadiness.

Until the NWPA is reinstated, inuksuit may be the only things standing guard over the places we paddle. Perhaps we should embrace them as our own, and consider them new recruits in an army of resistance gathering where they are most needed.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2009 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2009 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.