AGES 0–2: There is no such thing as too young. However, the safety considerations you would use on your own trips are magnified when a baby is involved. Small people are far more susceptible to hypo- and hyperthermia. All decisions revolve around keeping the baby warm (but not too warm) and dry. Put the baby in a sling to keep it close, or in your lap or on a foam pad on the cockpit floor. Use a large towel or umbrella for sun or drizzle protection.

Capsizing is not an option. Plan routes to minimize risk: no large crossings, close to shore, lots of spots to land and camp.

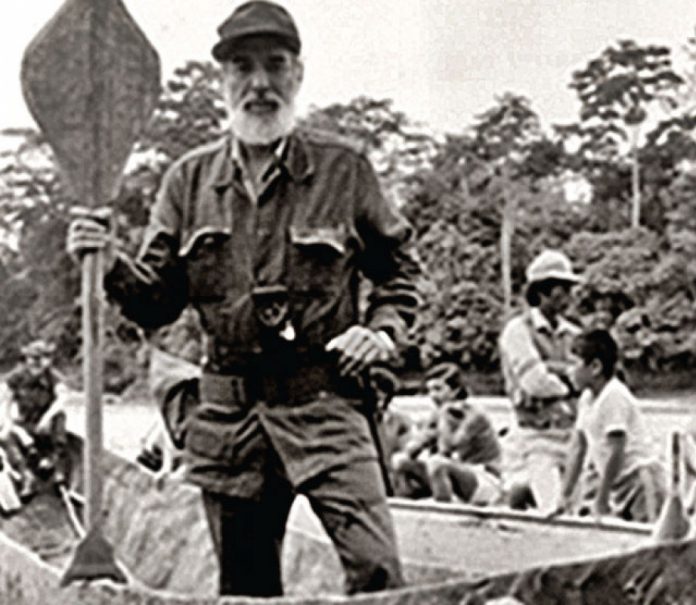

AGES 3–9: Michael Pardy, owner/operator of SKILS kayak and leadership school, saw the birth of his son Rowan not as the end of his paddling career, but as the addition of a new paddling partner.

“I never wanted rowan to remember his first time in a kayak. I wanted paddling to just simply be a part of his life,” explains Pardy.“So we have been paddling with Rowan since he could sit in our laps.”

Today, Rowan Jones-Pardy has spent more time in a kayak than just about any 11-year-old. The centre hatch of a tandem is where rowan spent much of his time on the water.

Pardy tries to include other families and friends in his and Rowan’s kayaking experiences, both for company for rowan and to help share the workload. The right boat helps, too. “The Current Designs Libra has a huge center hatch that allows kids room to move around, entertain themselves and be more comfortable.”

Pardy stresses the need to choose trips appropriate to this setup, keeping in mind that there is no spray skirt on the center hatch. “Obviously you can’t go out into conditions with large waves or exposed waters, but at this age the point is simply to get out on the water with your kids.”

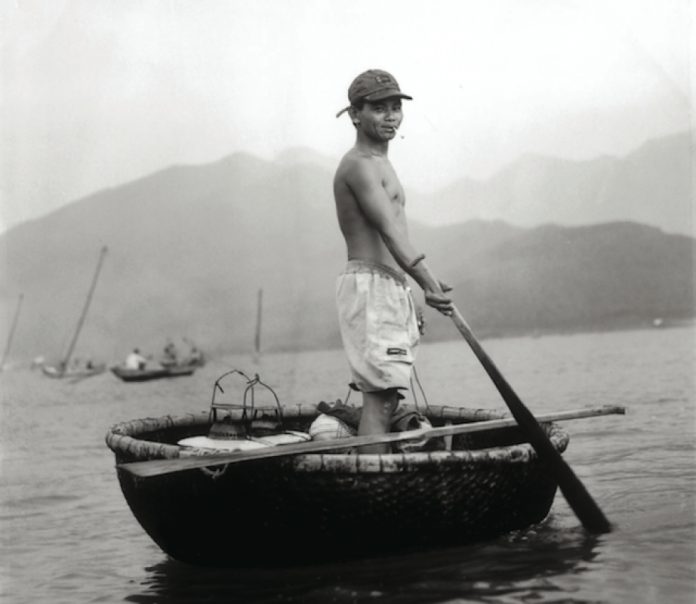

AGES 9 AND UP: Once they’ve developed basic paddling skills, as well as some strength and confidence, it’s time to get them into their own cockpit: the bow of a tandem or a small, properly fitted solo boat. Plan routes with many options to keep beach playtime long and paddling time short—an hour max on the water before and after lunch.

Consider a water taxi. If they don’t want to paddle, head for camp, hook up a tow, or take over in the stern. You may cover less ground than when they were just a toddler along for the ride. Have patience, and you may hear the words every paddling parent dreams of: “Where are we going next year?”

10 LITTLE THINGS THAT MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE WITH LITTLE ONES

Tea towel: For shade or to cool toddlers, or clean up unexpected eruptions.

Camp crafts: A small canoe paddle is ideal. Decorate it on a weather-bound day. Or tie a plastic fish to it so they can “fish” en route.

Cloth diapers: Simply rinse and air out on deck for reuse on long trips.

Hammock time: Critical for naptime—for both parents and kids.

Baby sling: great for toddlers and small children to keep close to mom or dad in the boat, or to free hands around camp (nurturedcub.ca).

Tarp: A good tarp is a fort, a mudroom, a shaded sanctuary, and a dry haven all in one. It keeps dirt out of the tent and provides a sheltered all-weather play area.

Friends: Yours and theirs. Other families help share the load and share the fun. If your kids are having fun, so are you.

Beach camps: Choose a nice flat, mellow, kid-friendly beach camp.

Backpack: Give your child their own daypack with their toys, sunhat, warm clothes and other gear. This helps build independence.

Umbrella: Great for sun and rain.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions