Imagine a smiling figure walking to the front of a crowded hall. Those nearby slap him on the back while the rest cheer. Stepping onto a stage he squints into rapid-fire camera flashes.

He grabs a paddle, raises it above his head and tells the crowd that if someone wants to take the paddle from him they will have to pry it from his “cold, dead hands.” The crowd roars; the politicians fall in line.

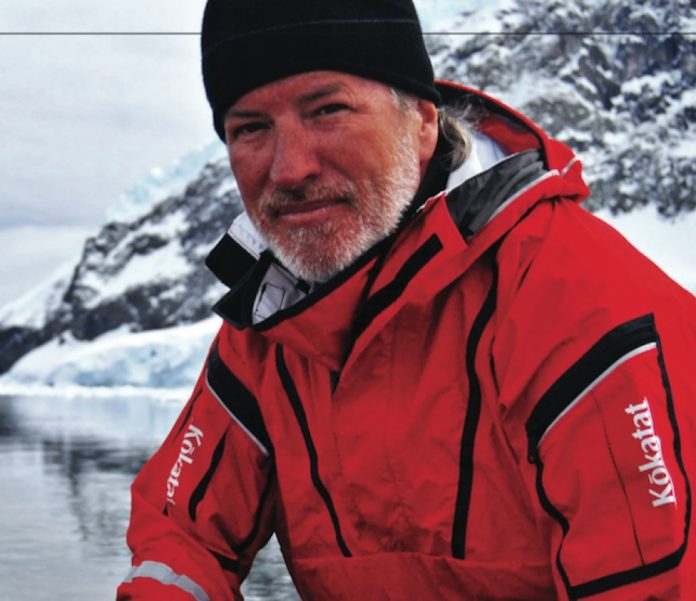

You probably have an easier time picturing a gun-toting Charlton Heston—movie star and former president of the National Rifle Association—in this situation rather than Paddle Canada president Richard Alexander. Here’s hoping Paddle Canada finds a way to put a little NRA firepower into its organization. The time may be coming.

As reported in the Summer 2008 issue of Canoeroots, Paddle Canada has entered a braided section of river and chosen what it hopes is the channel with the strongest current.

At first we were gun-shy about reporting on Paddle Canada’s political manoeuvres. Paddle Canada owns Kanawa magazine and the Waterwalker Film Festival, two ventures that compete, however politely, with Rapid Media’s magazines and our Reel Paddling Film Festival. We were wary of being seen as biased, but in researching the story I came to appreciate its importance.

BRINGING IN ADVOCACY AND LOBBYING

Paddle Canada was formed in 1976 to promote four pillars of recreational paddling: instruction, safety, environmental awareness and appreciation of our paddling heritage. It had struggled lately and some doubted it could continue fulfilling any part of its mandate. The 2006 sale of its member-built Ron Johnstone Paddling Centre headquarters and the liquidation of its inventory of boats, computers, staplers and a few paper clips fuelled the worries.

Alexander told me Paddle Canada will run a surplus this year for the first time in five years. He understandably feels a huge sense of accomplishment and credits the strength of the money-generating instructional program. But when I asked about the other quarters of Paddle Canada’s mandate the conversation slowed while we checked the website to remind ourselves what they were.

“Advocacy and lobbying are not primary purposes of this paddling organization,” explained Alexander.

Perhaps not now, but if Alexander continues to strengthen Paddle Canada, why couldn’t they become more a part of its purpose? Imagine for a moment if paddlers had a vehicle for wielding political influence. That’s where the famous scene with Charlton Heston comes in (the one from the NRA convention, not when he finds the Statue of Liberty on the beach in Planet of the Apes and goes ape).

The NRA marshals more than four million members, claims an 86 per cent success rate in helping the politicians it endorses get elected and is routinely ranked by members of Congress as the most powerful lobby group in the United States.

Paddle Canada could be similarly influential. After all, if the NRA can convince politi- cians not to renew a ban on semi-automatic assault rifles, which it did in 2004, then surely an activist paddling organization could lobby for more palatable things like fewer dams, more parks, rights of access and a halt to the creep of canoe licencing fees.

If we found our voice we could have politicians pandering to canoe-owning voters by promising chain gangs for portage clearing and long weekends every other week from May to October. Wide-brimmed Tilley hats would become a symbol of power and prestige.

What’s more, if we model ourselves after gun owners, our bumper stickers would become way more interesting.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine.

We spend two days at Cape La Hune not because of miserable weather—by now the Southwest Coast is fully enveloped in a 1,025-millibar high—but because it’s so hard to leave. Hiking up the breadbox-shaped peak behind the campsite oc- cupies an afternoon with scrambling up sloping rocks and crashing through tuckamore thickets of dwarf birch and fir trees. From the top, the Atlantic stretches uninterrupted to Antarctica, save for the inconspicuous dots of the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon to the south- east. Facing inland, La Hune Bay cuts a granite corridor through a sweeping expanse of tucka- more and barrens. On the treacherous descent I find an old threadbare rope—proof that the Cape La Hune outporters did more than just fish. Later on, I watch the moon rise over the rockbound coast from within the foundation of the old church, imagining the building itself departing on a barge bound for the horizon.

We spend two days at Cape La Hune not because of miserable weather—by now the Southwest Coast is fully enveloped in a 1,025-millibar high—but because it’s so hard to leave. Hiking up the breadbox-shaped peak behind the campsite oc- cupies an afternoon with scrambling up sloping rocks and crashing through tuckamore thickets of dwarf birch and fir trees. From the top, the Atlantic stretches uninterrupted to Antarctica, save for the inconspicuous dots of the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon to the south- east. Facing inland, La Hune Bay cuts a granite corridor through a sweeping expanse of tucka- more and barrens. On the treacherous descent I find an old threadbare rope—proof that the Cape La Hune outporters did more than just fish. Later on, I watch the moon rise over the rockbound coast from within the foundation of the old church, imagining the building itself departing on a barge bound for the horizon. This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions