In the early 1950s, European slalom paddler Milo Duffek invented the stroke that bears his name and changed slalom racing forever. When it comes to adjusting a boat’s direction, there is no stroke that can compare to the Duffek in efficiency and effectiveness. But it’s not just for slalom paddlers. The same effectiveness that made it revolutionary on the racecourse makes it useful for all paddlers who like to exert influence over which direction their kayaks point.

By mastering the Duffek and working an offside tilt into your turns, you’ll be able to catch narrow micro-eddies and make quick mid-stream changes in direction anywhere on the river. Unlike the reverse sweep, the Duffek allows you to maintain your forward momentum. Compared to the trustworthy low brace, the Duffek offers little stability yet really lets you snap your boat around.

You must Duffek, Duffek good

The Duffek’s different uses involve different set-ups, tilts and stroke combinations, but the essentials are straightforward. Paddle forward in flatwater and plant a vertical paddle away from the front of your boat at about a 45-degree angle. The paddle blade should be open so you feel pressure on the power face of the blade. Keeping your arms solid for support, use your abs to twist your torso and whip the boat around. Think of it as bringing your knees to the paddle. Once the boat reaches the paddle, you’re set to follow-through with a forward stroke.

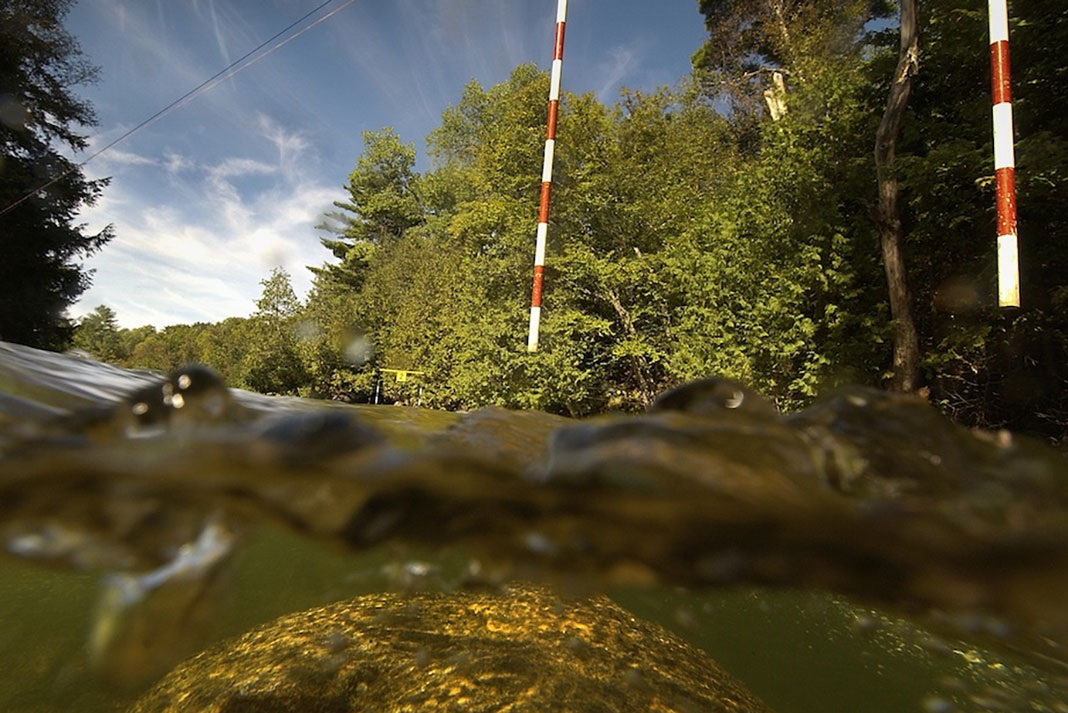

To help you visualize, think about swinging around a pole. Your paddle should be solidly planted in the water like a pole. You need to swing your body and boat around until you face the direction you want to go. That’s it really; just make sure that for now your top arm doesn’t come above your forehead, leaving your shoulder vulnerable to injuries.

Duffek into the current

When carving out of an eddy, cross the eddyline while tilting downstream and initiate the turn with a sweep. Plant the Duffek. Once the boat has turned and your paddle is next to your knee, pull on the blade with your forward stroke. As you enter into the current, you’ll feel the force of the water on the blade and your boat will turn very quickly.

Duffek into an eddy

When entering an eddy, the Duffek allows you to turn upstream quickly without drifting low or running too deep into the eddy.

Set yourself up to catch an eddy as you normally would. Punch the eddyline and initiate the turn upstream with a sweep. Plant the Duffek. Pull the boat to the paddle and then follow through with a forward stroke. In short boats, you won’t need to initiate with a forward sweep unless it’s a really strong eddyline or you’re approaching without a sharp enough angle. If you engage the outside edge of your boat immediately after your bow crosses the eddyline, the combination of an outside tilt and a Duffek stroke stops the boat from carving or sliding and it sticks your position in the eddy.

Duffek around the river

When we’re paddling around the river we always need to make minor adjustments to boat angle and the Duffek is the perfect stroke for this. Simply plant the Duffek in the direction you want to go, snap the boat to your paddle and paddle forward. The Duffek offers excellent control without compromising your forward momentum. This may sound similar to the draw. To avoid confusion, remember you use the Duffek to turn the boat and you use the draw to change lateral position, without changing direction.

Milo Duffek changed the world by developing a stroke combination with both stability (in the form of a high brace) and power (because it leaves your paddle poised for a forward stroke). Combine the Duffek with an outside edge tilt and you’ll discover that, 50 years later, you’ll enjoy having far more control over where you go on the river.

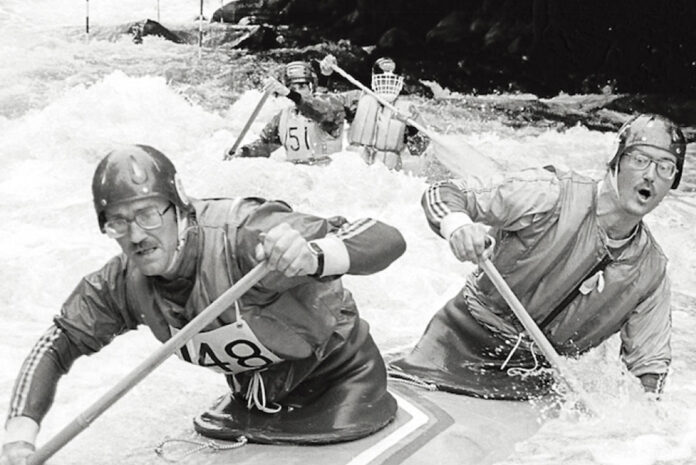

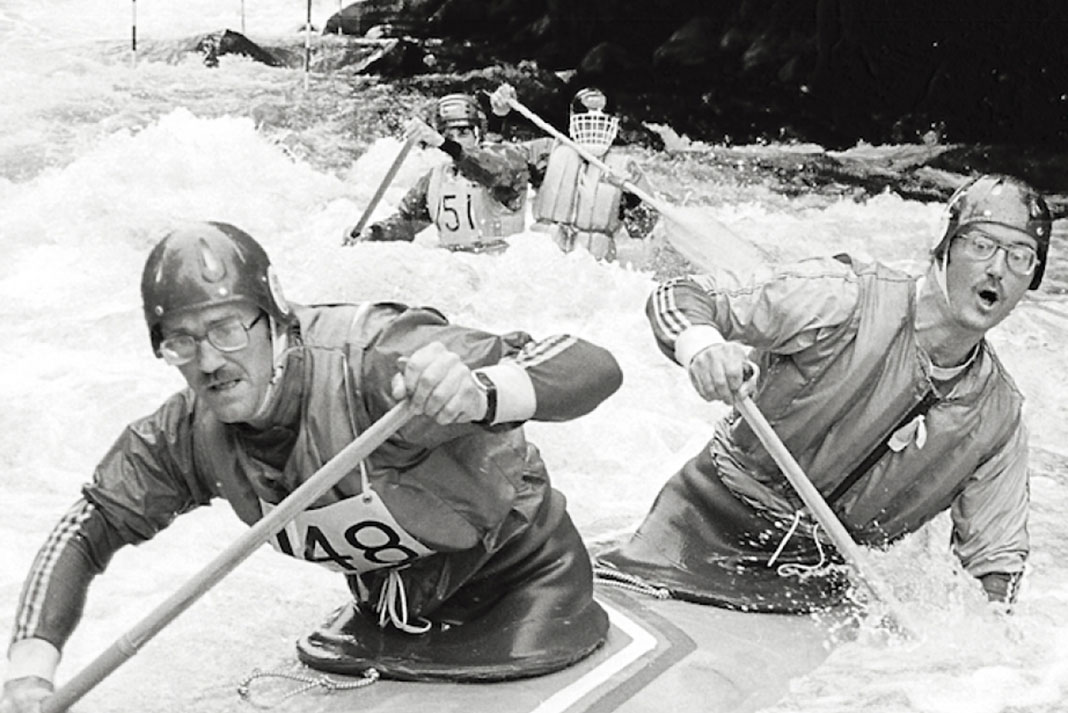

This stroke in history

Prior to the Duffek, paddlers turned kayaks by using a reverse sweep. Effective, yes, but reverse sweeps slowed down the boat too much to be useful in racing. Milo Duffek, a native of Czechoslovakia, unveiled his secret weapon—the Duffek—for the first time at the 1953 World Championships in Merino, Italy.

As competitors watched Milo practice, word of the new stroke spread and the question became not if he’d win, but by how much.

This is where the story takes a dramatic turn.

Milo Duffek had come to Italy with plans that were more ambitious than winning hold. Duffek was going to defect. Escaping from his newly communist Czechoslovakia for the freedom of Western Europe was more important to him than a medal. As the story goes, Duffek purposefully hit the outside of gate 14 with his bow. This was a 100-second penalty in those days, and enough to drop him to second place. This second-place finish removed Duffek from the limelight and allowed him enough anonymity to skip town with the Swiss team.

Sarah Boudens is a member of Canada’s Slalom Development Team.

Duffek for freedom. | Destination Ontario

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2005 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2005 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Summer 2005 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Summer 2005 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.